No one knows how it’s going down

… except for maybe Jackie Brown

By Mark Voger, author, “Monster Mash: The Creepy, Kooky Monster Craze in America 1957-1972″

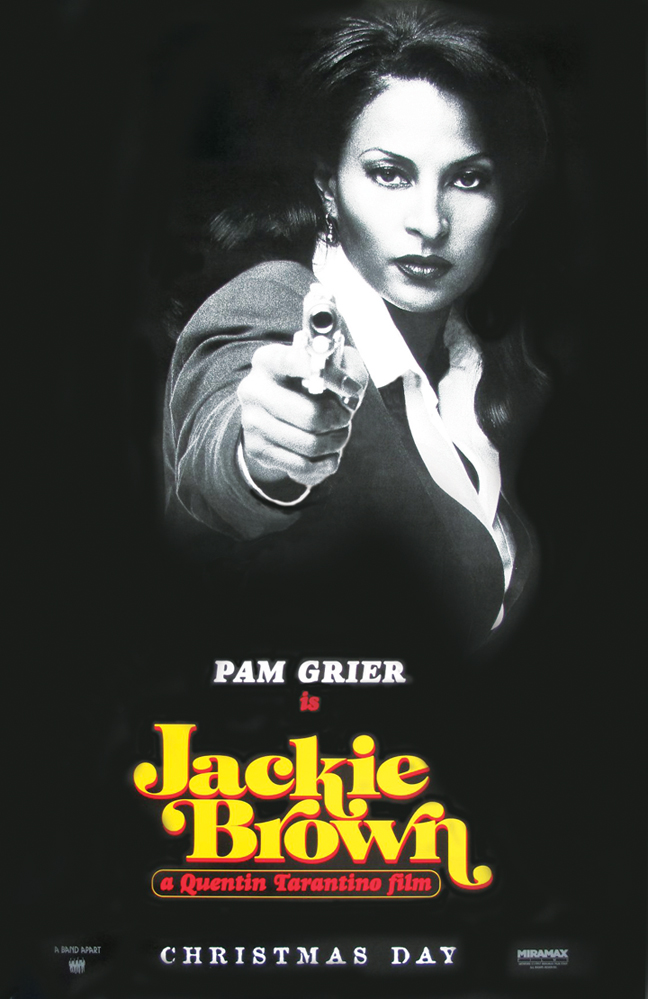

There’s so much going on in “Jackie Brown” — the ensemble cast, the infectious score, the force of nature that is Pam Grier — that it’s rare to hear Quentin Tarantino’s 1997 valentine to Grier’s career characterized as a “heist” movie.

But “JB” is one of the best, and deserves to be put on a pedestal alongside “Rififi” and “The Killing.”

It’s also Tarantino’s most “grown up” movie to date. No caricatures, no trendy dancing, no set pieces Xeroxed from treasured genre memories, no roles bestowed upon undeserving friends — you can believe everything you see on the screen.

In her first starring movie role in 22 years (since 1975’s “Friday Foster”), Grier plays Jackie, a 44-year-old stewardess for a low-rent airline who smuggles cash for scary gun-dealer Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson). After being collared by a federal agent (Michael Keaton) and an L.A. detective (Michael Bowen), Jackie faces jail time — or certain death at the gloved hands of Ordell, who doesn’t believe in allowing cohorts to remain above ground once the law gets to them.

With all eyes on Jackie, it’s hardly an ideal time to hatch a plot to steal a half-million from Ordell under the feds’ noses. But Jackie finds an ally in smitten bail bondsman Max Cherry (Robert Forster), a no-nonsense pro with a fresh barbershop haircut who has fallen hard for our heroine.

The heist is replayed three times from various points of view — those of Jackie, Max and Ordell’s associates Louis (Robert De Niro), an ex-con, and Melanie (Bridget Fonda), one of Ordell’s kept women.

Jackie keeps everyone guessing — the good guys, the bad guys and even the audience. Tarantino has a way of playing with time — how many movies have split-screen flashbacks? — or fading to black during a conversation, thus teasing, and withholding information from, the audience.

Also remarkable is Jackie’s transformation as she plays both sides against the middle. At first, she looks beaten in her stewardess uniform, or with unkempt hair following release from jail, or wearing an old bathrobe in her dreary apartment. But as her plan falls together, Jackie breaks out the good stuff in her closet. When Jackie barges into Melanie’s pad in a body-hugging red dress to forcefully deliver a pointed lecture to Ordell, you’d swear it was 1973 again.

After the smoke clears, and Jackie drops in on Max’s office for what is clearly a farewell meeting, she says to him, “I didn’t use you, Max.” Note to dudes: When a chick says “I didn’t use you,” it means she used you. But you knew it all along, didn’t you, and so did Max. Forster’s expression of surprise (and of fleeting joy) at receiving a kiss from Jackie, even a goodbye kiss, is quite a piece of acting.

There are references to Grier’s early hits like “Coffy” and “Foxy Brown.” But for once, Tarantino is subtle about putting his cinematic scholarship on display. There are no blinking neon signs here. Instrumental themes from “Coffy” (by jazz great Roy Ayers) are borrowed, but always appropriately, so as to not take you out of the movie. (And, man, I’m tellin’ ya, Ayers’ funky “Coffy” jams belong in more movies.)

Another tradition from the earlier films is multiple fashion looks for Grier. She wears a cute beret (one that conjures the vigilante groups you’d see in blaxploitation films) in the Del Amo Mall scenes; dons a badass suit in the heist scene; and wears an outfit in a bar that prompts Ordell to comment that she’d need “n***** repellent” on a Saturday night. Not to mention that red dress.

My favorite reference to classic Grier – and I admit I may be projecting here – is Tarantino’s final scene. It’s a lingering, wordless shot of Jackie as she drives away from the whole mess, hopefully forever. You feel like you can read her mind. She seems to be reliving what she just went through, smiling slightly at how things turned out. Jackie sings along with Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street” (the opening theme reprised) on her car stereo, not that you can hear her.

In “Coffy,” under much different circumstances, writer/director Jack Hill includes a likewise wordless scene of Grier’s character driving, lost in thought.

I can’t help but think that Tarantino is recycling this device as his way of saying: You see? Coffy won. Again.

View “Monster Mash” 34-page preview