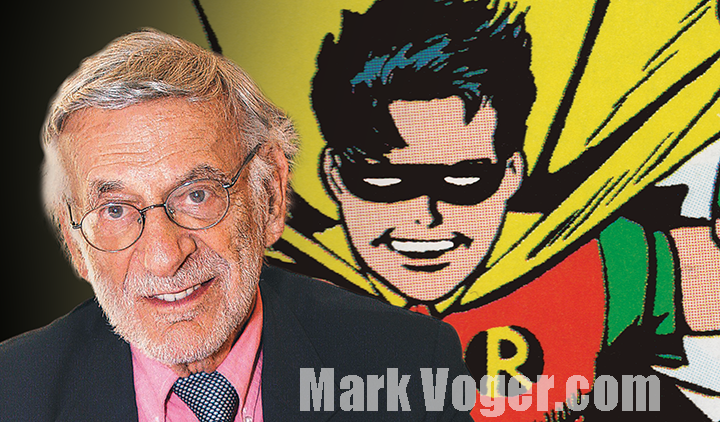

Following are excerpts from “Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships July 31).

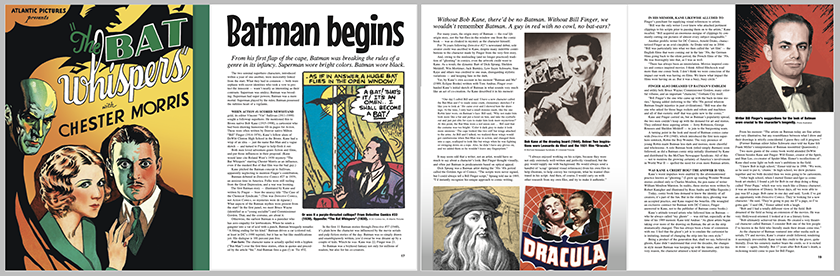

Batman begins

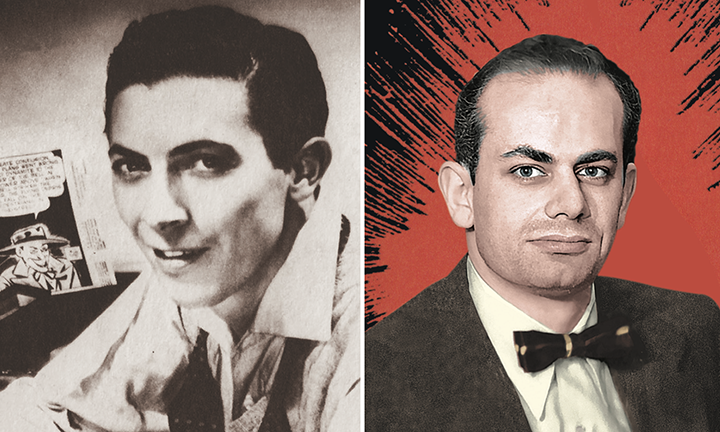

After Action Comics #1 introduced Superman, its editor Vincent “Vin” Sullivan (1911-1999) sought a followup superhero. He mentioned this to Bronx native Bob Kane (1915-1998), a cartoonist who had been drawing humorous fill-in pages for Action. These were often written by Denver native Milton “Bill” Finger (1914-1974), Kane’s fellow alum of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. Kane had a wisp of an idea — just the name Bat-Man and a vague sketch — and turned to Finger to help flesh it out. Both men loved adventure-genre fiction and films, and put those influences in their proposal.

Kane successfully pitched the Batman concept to Sullivan, apparently neglecting to mention Finger’s contribution.

Batman debuted in Detective Comics #27 in 1939, an anxious time in America. Folks were still reeling from the Great Depression, and a war was looming. The first Batman story — illustrated by Kane and written by Finger — bore the unsexy title “The Case of the Chemical Syndicate.” (This was Detective Comics, not Action Comics, so mysteries were de rigueur.) What aspects of the Batman mythos were present from the start? In the first panel, we meet Bruce Wayne (identified as a “young socialite”) and Commissioner Gordon. That, and the costume, are about it.

Otherwise, the earliest Batman is a punisher who has zero empathy for lawbreakers. When he sends a gangster into a vat of acid with a punch, Batman brusquely remarks: “A fitting ending for his kind.” Batman drives a car (colored red, at least in DC’s 1990 reprint), but it has no bat-like modifications yet.

In the first 11 Batman stories through Detective #37 (1940), it’s plain how the character was influenced by the movie serials and pulp fiction stories of the day. Batman was so simply drawn and unambiguously written, you’d swear he was dreamt up by a couple of kids. Which he was. Kane was 22; Finger was 21. So Batman was a boyhood fantasy not only for millions of readers, but also for his co-creators

The Kane-Finger saga

Without Bob Kane, there’d be no Batman. Without Bill Finger, we wouldn’t remember Batman. A guy in red with no cowl, no bat-ears?

For many years, the origin story of Batman — the real life origin story, not the bat-flies-in-the-window one from the comic book — was as cloaked in mystery as the character himself. For 76 years following Detective #27’s newsstand debut, sole creator credit was ascribed to Kane, despite many indelible contributions to the character made by Finger from the very first story. And, owing to the misleading (and no longer practiced) tradition of “ghosting” in comics, all artwork credit went to Kane whether he drew it or not.

As a result, the dynamic art of Dick Sprang, Sheldon Moldoff, Win Mortimer, Jack Burnley, Lew Sayre Schwartz, Stan Kaye and others was credited to one man, disregarding stylistic variations — and keeping fans in the dark. Yet, by Kane’s own account in his memoir “Batman and Me” (1989, Eclipse Books) written with Tom Andrae, Finger over hauled Kane’s initial sketch of Batman in what sounds very much like an act of co-creation.

As Kane described it in his memoir: “One day I called Bill and said ‘I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I’ve made some crude, elementary sketches I’d like you to look at.’ He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman’s face. Bill said, ‘Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?’ At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit … Bill said that the costume was too bright: ‘Color it dark gray to make it look more ominous.’ The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to the arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action, and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope.”

Jerry Robinson

On co-creating the Joker: “My idea was to create a new villain, because there weren’t supervillans in the comics at the time. From my studies in literature, I learned that all the great heroes from Biblical times on had an antagonist. Even Sherlock Holmes had Moriarty. But we never had one for Batman.

“I had written a lot of humor pieces in my courses at Columbia. I wanted to create a villain that had some sense of humor. That would be a contradiction in terms, a villain with a sense of humor. That is the essence of a good character: It has contradictions.”

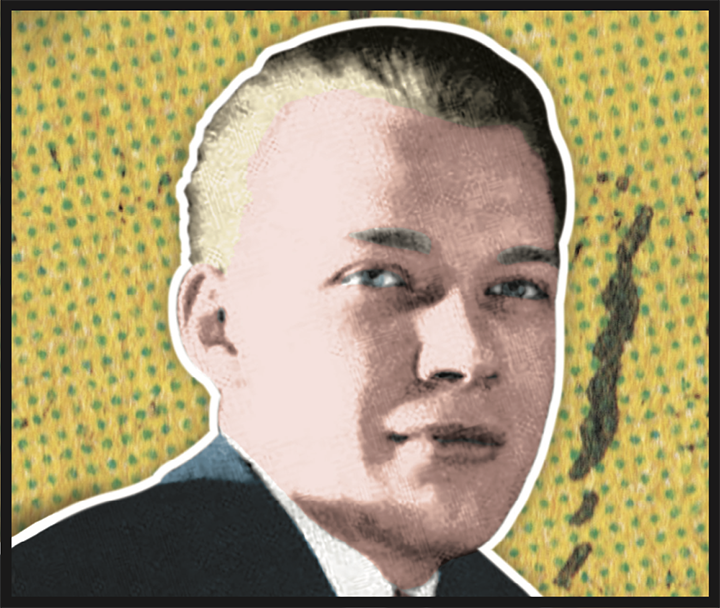

Dick Sprang

On illustrating the exploits of Batman: “Unlike Superman, Batman was vulnerable. He could be hurt, overpowered, so the reader could identify with him. His goals were simple. His methods of fighting crime were brainy as well as physical. He wasn’t a dumb, macho hero battling a bunch of stupid crooks.

“His power resided in the thrust of his intellect and his athletic ability. He commanded respect as a wary and resourceful avenger. Of course, looming out of the night added to the dramatic impact.

“I enjoyed drawing Batman for the challenge of the many things that the writers and editors would find for him to do — a great tapestry of adventure in all parts of the world.”

Pre-order at TwoMorrows | Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Target | Previews World

See 62-page preview HERE

Read 13th Dimension’s preview HERE