Following are excerpts from “Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships July 31).

The ‘New Look’

Was Julius Schwartz DC’s unofficial “fixer”? Its editorial pinch hitter? Its superhero whisperer? When the avowed science-fiction guy — Schwartz abhorred the phrase “sci-fi” — joined All-American Publications in 1944, he didn’t know from superheroes or even comic books. But he caught on quick.

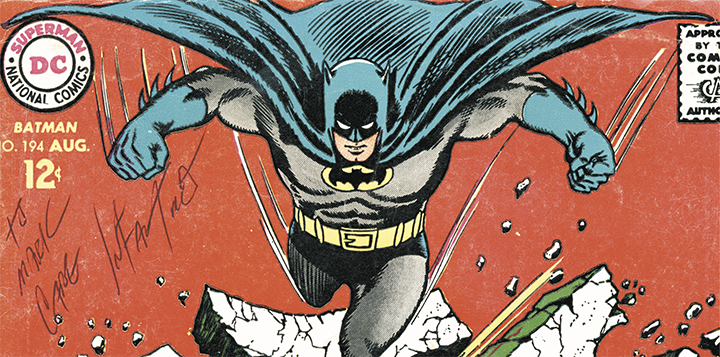

In 1956, he reintroduced the Flash in a top-down revamp — new costume, new origin, new secret identity, same powers — illustrated by Carmine Infantino in Showcase #4. Schwartz next revamped the Green Lantern, the Atom and others. So taking over the reins of Batman from outgoing editor Jack Schiff at the behest of publisher Irwin Donenfeld was a bit of deja vu.

“Batman was floundering back in 1964,” Schwartz told me. “I was given the Batman; I didn’t want to do it, because it meant giving up my science-fiction comics. But the powers-that-be insisted, and I took it over. I did with Batman as I did with Flash and Green Lantern. I didn’t change the origin or anything like that, but I introduced a lot of new concepts, which I called the ‘New Look.’

“When I took over Batman, I said, ‘I don’t want to use Bob Kane’s artwork.’ I said, ‘I want to use my main artist, Carmine Infantino.’ So they said, ‘Well, we can’t let Bob Kane go. He’s under contract. So why don’t we simply alternate? Carmine does one story, Bob Kane does another.’ That agreement was reached, so I used Kane one issue and Carmine another. But it was I who insisted that Batman needed a breath of fresh air. Eventually, of course, Kane left (in 1966) and I didn’t have to use him anymore.”

There was a practical reason why Schwartz directed Infantino to add a yellow circle around the bat logo on Batman’s chest. “That was my idea, mainly because I couldn’t see it (the bat logo),” Schwartz said. “I wanted to highlight it. Of course, when the ‘Batman’ movie came out (in 1989), that’s all you saw was the bat insignia encased in a yellow circle!”

Creating Batgirl

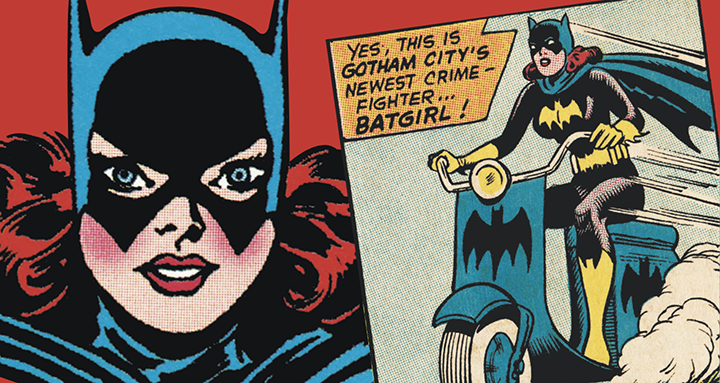

Batman was a product of inspiration — of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, of pulp fiction stories featuring the Shadow, of old-timey films like “The Mark of Zorro” and “The Bat Whispers.” As for Batgirl, she was a product of desperation — of a TV producer, fretting over sagging ratings, calling up a comic book editor to come up with a new female-friendly character, pronto.

The year was 1967. Julius Schwartz was then in his fourth year as editor of DC’s Batman line of comics. As he told me in 1997: “After the first year of the ‘Batman’ TV series, the ratings started to fail. So (executive producer) William Dozier asked us to bring in a female interest. Now, whether he or I or whoever came up with the idea of a Batgirl, I don’t remember.

“We made her the daughter of Commissioner Gordon. Carmine Infantino designed the uniform — she rode around on a motorcycle, as I recall — and Gardner Fox wrote the story, which was called ‘The Million Dollar Debut of Batirl’ (in Detective Comics #359). Evidently, they liked it. They liked the whole design, and they adapted it to the television series.”

Schwartz recalled that 30 years later, he and actress Yvonne Craig, who played Batgirl on TV, were appearing at the same fan convention in Georgia. Recalled Schwartz: “So I went over to her — pushed everyone out of the way — and I pointed a finger at her and said, ‘I created you.’ ” Craig was taken aback until Schwartz explained his role in the creation of Batgirl.

“So she thanked me very much and gave me a kiss on the cheek, see? A good reward. A good reward.”

The superhero glut

Why should DC and Marvel have all the fun … and profit?

First there was the unanticipated rise of Marvel Comics after a decade of struggle under the Atlas moniker. Then came Batmania, and the comic book industry got the memo: It was clobberin’ time.

Publishers beyond the “Big Two” began dusting off long-dormant properties and whipping up a slew of newbies, with wildly varying results. Thus, readers faced a glut of superheroes in the middle 1960s. Overwhelmingly, these books were not on a par with DC and Marvel, even if a surprising number of “name” artists filled their pages: Joe Simon, Steve Ditko, Mike Sekowsky, Chic Stone, Wally Wood, Kurt Schaffenberger, Gil Kane, Jim Steranko and, via reprints and leftovers, Jack Kirby.

There were some wacky-ass superheroes: Super Dracula and Super Frankenstein (not their official names, but that’s what everyone calls ’em now); Jughead “as” Captain Hero; Betty “as” Superteen; yet another Captain Marvel (who lost his head and limbs by yelling “Split!”); and the Fab Four, a superteam calling itself the “mightiest superheroes in the world.” Readers didn’t agree. Their book Super Heroes (now there’s a compelling title) lasted only four issues.

Pre-order at TwoMorrows | Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Target | Previews World

See 62-page preview HERE

Read 13th Dimension’s preview HERE