What’s in a name

By Mark Voger, author

“Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture”

“The challenge I face in taking over the brand is that it’s not like starting a new business. You get what you get. You inherit — I can’t say I ‘inherited’ it. I bought the business. It was not handed to me. The company was failing, which was heartbreaking. I’m trying to revive it.”

So says Stephanie Stuckey — whose grandfather founded the venerable Stuckey’s chain of roadside rest stops in 1937 — on reclaiming the brand that bears her family name.

Georgia native Stephanie, 55, grew up in Washington, DC (at 6, she once famously chided President Nixon); was an environmental lawyer; and served in the Georgia House of Representatives from 1999 until 2013. So re-acquiring the Stuckey’s brand is only the latest venture in her storied career, and it’s a daunting one.

“We are now profitable, which is a huge achievement considering the pandemic,” she says. “But we’re far from where we need to be. We don’t own any stores. The franchise agreements give franchisees a lot of leeway. There are stores I’d like to de-brand or re-brand — a third of them, frankly. The problem is, we need funds, we need the franchise fees. Ideally, we would have corporate-owned stores. I’m trying to find developers who would buy and build stores.”

Childhood memories

Ethel Stephanie Stuckey’s childhood memories of the Stuckey’s chain are less ingrained than you might assume. She points out that the company was sold in 1964, a year after she was born. When her father, William Stuckey Jr., was elected to Congress in 1966, he relocated his family to Washington. As such, young Stephanie was not fully aware of the breadth of Stuckey’s significance.

“Certainly, I grew up with ties to Stuckey’s, but not with a real understanding of the business,” she admits. “Growing up in Washington, I didn’t really know what Stuckey’s was. President Roosevelt’s granddaughter was in my class; President Truman’s grandson was in my class. Nobody knew about Stuckey’s.”

(Her first brush with fame occurred when, as a 6-year-old at a Beltway function, she informed Nixon that she hadn’t voted for him. She and Nixon then had a cute, though pointed, exchange as the media looked on.)

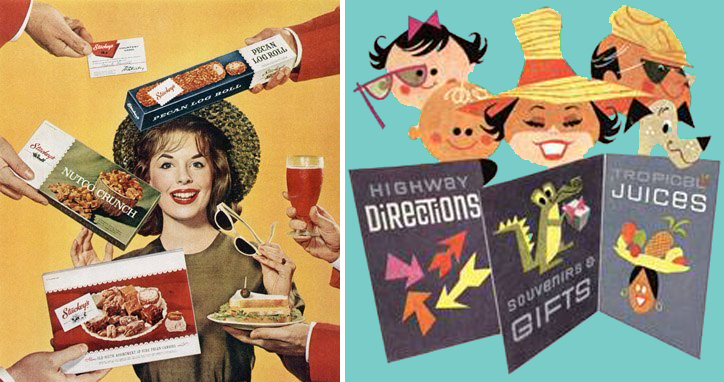

Despite not being immersed in Stuckey’s lore as a child, Stephanie still has fond memories of visiting the Georgia office and candy plant of her grandfather, William S. Stuckey Sr. (1909-1977), who founded the chain which — during the golden age of interstate travel (particularly to vacation destinations in the South) — promised road-weary families cold drinks, clean restrooms and, most memorable of all, pecan candies, especially the iconic Stuckey’s Pecan Log Roll. (My fillings ache just thinking about it.)

Origin story

Stephanie was named after her paternal grandmother, Ethel Stuckey, who played a vital role in the creation of the Stuckey’s brand.

“I knew her well, but she never talked about the business. I know the story from what my father told me,” Stephanie recalls.

“My grandfather had his pecan stand out in the middle of nowhere in Eastman (Georgia). My grandfather was one of those people who, when he had an idea, he just did it. So he was running that stand, and cars were driving by, and he said, ‘I should sell candy.’ He ran to the house, which was a mile away, and interrupted my grandmother’s bridge game, telling her, ‘You need to make candy.’

“My grandmother had six sisters. They went into the kitchen and started making candy. The pecan log was an old Southern recipe.”

Ethel’s candy was a hit, and Stuckey Sr. built his business up from there, opening a proper store and then adding locations until the Stuckey’s chain became something like an empire.

“We were the first real roadside retail chain on the interstate,” Stephanie says. “My grandfather saw the need for that. Families wanted an affordable stop where they could find everything they needed. He didn’t want it to be a sit-down restaurant. There would be a snack bar and some seating, but no wait staff.”

‘Quiet’ policy

The chain was founded in the South during the era of segregation. But Stuckey Sr. enforced a policy whereby no customers were denied access or service because of the color of their skin. It’s something Stephanie doesn’t recall her grandfather ever talking about.

“But my father did many years later,” she says. “Because in those times, it was not a popular opinion.

“My grandfather always kept his stores open to all people, but it was a ‘quiet’ policy. The way he lived his life was, he elevated women and African-Americans. He did the right thing, but he didn’t talk about it. He was not a braggadocious person.”

One possible reason behind Stuckey Sr.’s policy was the loyalty and hard work of an early employee who happened to be black.

Recalled Stephanie: “My grandfather started the company, really — before the pecan shed — by driving around the countryside, buying pecans and selling them to pecan processing plants. He employed a helper named John King, who was African-American. John King helped my grandfather get started. They used to work so hard, so late into the night, that they would sleep on bales of pecans on their truck! John King remained with my grandfather for the rest of his life. He eventually became a half-owner of a Stuckey’s store. Back in the day, that was unheard of.

“My grandfather would say the only color he discriminated against was people who didn’t have green: ‘If you have money, you’re welcome in my stores.’ His restrooms were not segregated. We were in The Green Book (a segregation-era travel guide for African-Americans). He also privately donated money for college tuition for African-Americans. He did things like that, but he was very quiet about it.”

After Stuckey Sr. sold the chain, according to Stephanie, “It was out of our family’s hands for decades, and business plummeted. My dad got the company back (in 1984). But my dad was running four other businesses. I don’t understand why he didn’t give it his full passion — well, I do understand. His other businesses were more profitable. He shut down stores. He re-branded Stuckey’s with this ’80s stuff — the blue roofs and a new, tri-colored logo. I said, ‘I love you, Dad, but it looks cheesy.’”

When Stuckey Jr. retired 10 years ago, Stephanie says, “There was no CEO, no strategic plan, no marketing development. It was dying. Who would buy it? Nobody wanted it. I thought, I’ll buy it. But wait — if I buy it, who will run it?”

As the adage goes: If you want something done right, do it yourself. Stephanie decided to take on that mantle herself. “Within six months, we started turning a profit, which is incredible,” she says.

Sign(s) of the times

Stephanie and I first became acquainted after I posted an article about visiting a Stuckey’s location where I saw many pro-gun-ownership signs for sale. (This struck me as being out-of-place for a “family” store.) She points out that the location — in Summerton, South Carolina — is owned by a nephew of hers, and she stresses that the pro-gun signs are not Stuckey’s products per se.

“If you see branded Stuckey’s products — signage on displays that carry the Stuckey’s name — that’s us,” she says. “Those metal signs, we’re not sourcing. I don’t buy those signs. Personally, I’m not a gun-toting NRA person. I cringe when I see that. But those signs sell. Those are our customers. They stop there.

“Even if I wanted to dictate what the stores sell, under the franchise agreement, I could not say, ’You can’t sell those signs.’ Even if I don’t agree with them. When I was in the Georgia House (of Representatives), I got a failing grade from the NRA every year. So it’s averse to what I believe in, but I must respect it.”

Despite having her hands tied by the franchise agreement, there is a line in the sand for the CEO of Stuckey’s Corporation.

“If I see one more Confederate flag (for sale), I will literally throw them through the window,” she says. “We will de-brand you tomorrow. So I did get the Confederate flag stuff out of there. I’m hoping that maybe people realize: Georgia didn’t go for (President) Trump (in the 2020 election). Maybe they should temper it a little. I wish I had ‘a’ store, so I could show how this model works. You don’t have to sell sub-par merchandise.

“I really am trying to ramp up the merchandise line. Since I can’t afford market research, I’m doing posts on Facebook. I ask followers what products we should be selling. I pay attention to those posts. ‘We want (the magnetic toy) Wooly Willy.’ ‘We want dunking birds.’ So I got dunking birds and put them in gift boxes. Those are selling like crazy.

“We’re in the process of buying a candy plant. My dream is to have, like, 20 really good Stuckey’s stores on the interstate. But what I really want is to drive our product by selling our product. Stores aren’t our future. Our future is the product.”