Following are excerpts from “Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships July 31).

A terrible way to go-go

It was once the Greatest Show on Earth. And then it was thrown away like the crumpled wrapper of a McDonald’s cheeseburger.

William Dozier, who lovingly shepherded the crazy, colorful, one-of-a-kind production that was “Batman,” sounded like the opposite of wistful or apologetic in justifying the show’s cancellation in 1968, after a third season marked by belt-tightening.

“Not bad for what was essentially a novelty show,” Dozier told an interviewer at the time. “In the last rating, the show was still leading in its time period, but adults had wearied of the series, and the audience had become more and more juvenile. The kids don’t care if it’s a repeat. So why go on spending $87,000 for new ones?”

This was what Adam West feared, that once “Batman” had enough shows in the can to play in reruns, the plug would be pulled. Another fear was that post-“Batman,” West would be typecast as the character, as had happened to Johnny Weissmuller (for playing Tarzan) and George Reeves (for playing Superman).

This dire prophecy came true to a degree, although West kept plugging, kept striving to find roles that weren’t throwbacks to his cape-and-cowl past. But when the chips were down, West agreed to put on what Reeves once called a “monkey suit”: his costume.

Hanna-Barbera — hardly renowned for live-action productions — hired West, Burt Ward and Frank Gorshin to reprise their “Batman” roles in two 1979 specials titled “Legends of the Super Heroes.” The shows were on videotape with a laugh track — basically “Hee Haw” without the country music. Tuxedo-clad Ed McMahon said hilarious things like, “I haven’t seen people dressed like this since I had lunch at Alice Cooper’s house.” Adding insult to injury, the costumes fit West, Ward and Gorshin less ideally 11 years after the fact.

When I once brought up the subject of the 1979 specials to West, he batted away the question with the cryptic statement, “Some things are better left unsaid.”

Batmania’s second wave

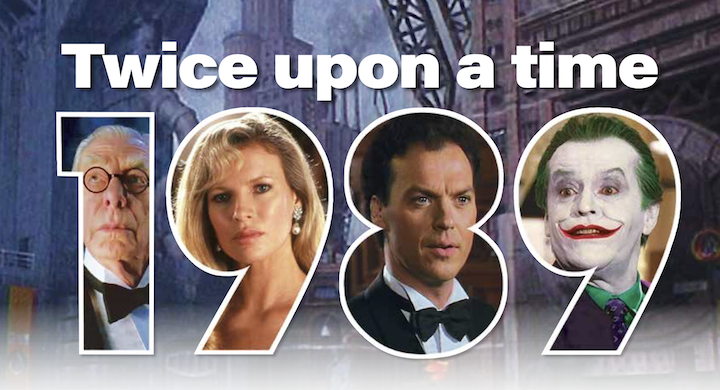

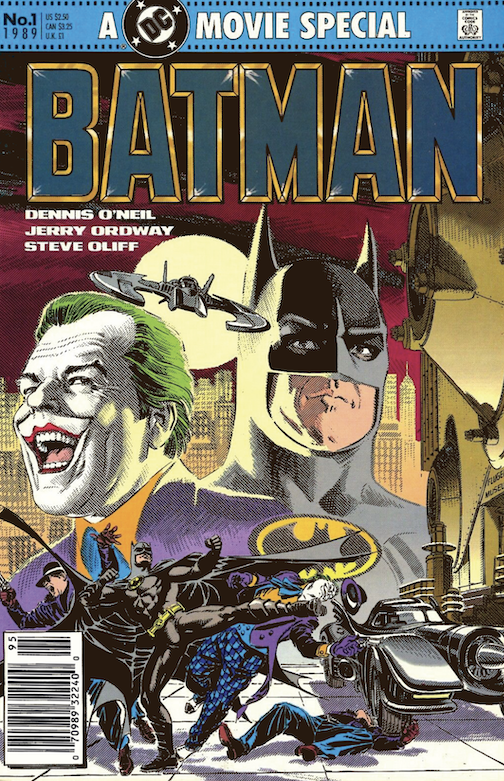

There was a full-fledged Batman craze going on in America. Topps put out Batman trading cards. The Ertl Company put out miniature Batmobiles at 1:64 scale. Batman action figures lined the shelves of toy shops. DC put out a comic book adaptation of a Batman movie. Ralston put out Batman cereal, a sugary, crunchy, oat-based product in the shape of tiny bats.

Nope, I’m not talking about the 1966 Batman craze. I’m talking about the 1989 Batman craze.

In the world of fandom, there were Batman purists who weren’t enamored of the 1966-68 TV series “Batman.” They believed Adam West’s portrayal poisoned the public perception of Batman, made him a buffoon. They believed that after the TV show, a new wave of younger, more serious-minded comic book creators had to work overtime to restore Batman to his roots as a mysterious figure of the night. They believed that by the time writer-artist Frank Miller produced his norm-shattering noir-ish serialized graphic novel Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), the stench of the ’60s TV show was finally eradicated, paving the way for Tim Burton’s 1989 film starring Michael Keaton as an unkinder, ungentler Batman.

This became the prevailing narrative. But further discussion is in order.

First off, we’re talking about two distinct realms of fandom: that of film and that of comic books. These two groups have been known to cross-pollinate, to be sure, but for the most part they are separate bodies. Film audiences count comic book geeks in their number, but overwhelmingly, their demographics are more mainstream. (You’d be surprised how many fans of superhero movies have never opened a comic book.) Meanwhile, comic book readers tend to be more niche.

In any case, Batman did just fine in the comics between 1968 and 1989. The character’s trajectory was reset. Batman rolled with the times, as long-running characters do in this venerable medium. He survived and thrived. Batman’s onscreen presence was a different story. After the cancellation of the 1960s TV series, Batman was thrown into cinematic limbo for those 21 years.

New Batman in town

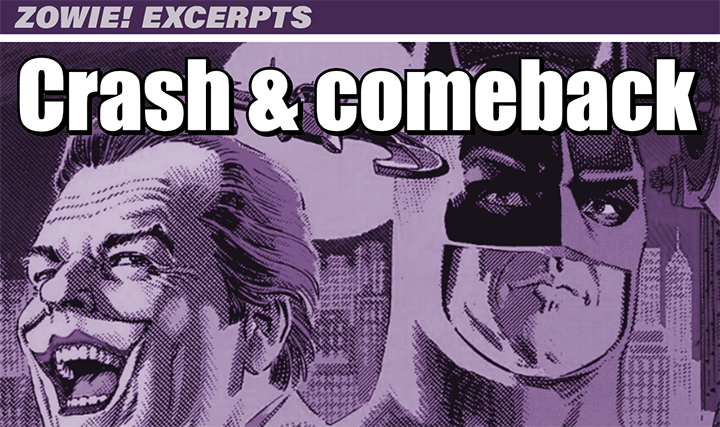

Perhaps Batman’s 21-year hiatis from film production was necessary, to ensure that mainstream audiences couldn’t possibly confuse a serious new movie Batman with Adam West in his periwinkle tights. And yet, in its way, the 1966-68 Batman actually helped the 1989 Batman. When the ’89 movie was green-lit, and filming commenced at Pinewood Studios in England — with Burton directing Keaton, Jack Nicholson (as the Joker), Kim Basinger (as Vicki Vale) and Michael Gough (as Alfred) — the 1960s TV show gave the production a boost, a nudge, a push.

Wha? I’m guessing the movie people would vehemently disagree, but my perspective is somewhat different. In a time before the internet, what was then called the “mass media” — chiefly TV, radio, magazines and newspapers — went whole hog in their preview coverage of the ’89 “Batman.” Beginning in 1988, even, video segments and print articles about the forthcoming film appeared with increasing regularity. Burton’s still-lensing movie became a “highly anticipated” publicity magnet.

Here’s where the view from my little perch comes in. By the late ’80s, a lot of folks in the media were “baby boomers” with fond memories of the 1960s TV series. (I, then a humble writer-designer for newspapers, was among them, albeit on a very low rung.) Simply put, they often had great affection and good will for Batman, and the idea of a new Batman movie caught their fancy. So any Batman-related development or press release or story that crossed their desks had a built-in edge, and often resulted in coverage via the aforementioned video segments and print articles. Mind you, many of these editors, reporters and TV people weren’t exactly “hep” to the nuances of the 1989 Batman. They were carelessly lumping him together with the 1966 Batman, and as such, blurring the line between them.

This muddling-of-message can be summed up with one regrettable recurring example. Quite often, a lead-in to a Batman-related video segment, or a newspaper headline, would say something along the lines of (I’m paraphrasing) “Pow! Bam! Tim Burton to direct new Batman movie.” The POWs and BAMs were clearly referencing the television Batman. But Burton’s film would not have any POWs, BAMs or even ZOWIEs. The 1966 Batman and the 1989 Batman were worlds apart.

But this tsunami of coverage, even if occasionally off-message, had a positive effect. Anticipation built steadily for Friday, June 23, 1989, the day “Batman” would premiere. Some advertisements merely showed the Batman logo and the date. Further elucidation was unnecessary. The film’s success became a foregone conclusion.

This leads us to another train of thought. If 1966 helped promote 1989 into a juggernaut, and the 1989 “Batman” triggered the superhero movie trend that followed and would dominate the cinematic world for more than a generation, then one could argue that the 1966 Batman played a considerable (albeit, indirect and woefully underacknowledged) role in the ongoing popularity of the superhero movie genre itself. Please — no death threats.

Pre-order at TwoMorrows | Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Target | Previews World

See 62-page preview HERE

Read 13th Dimension’s preview HERE