Following are excerpts from “Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships Nov. 4).

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.

Li’l page turners

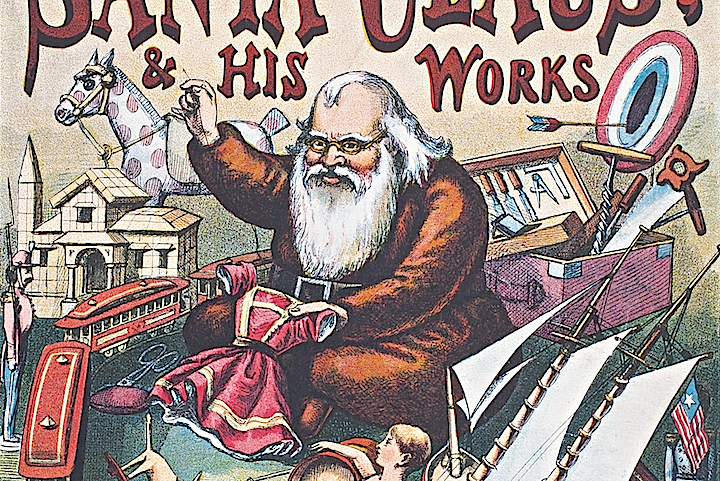

In his earliest known depiction in a book, Santa is a vengeful fella.

This Santa from 1821 — then called “Santeclaus” — believes in corporal punishment. Bad children don’t get presents; rather, their parents receive a rod with which to administer beatings:

“But where I found the children naughty / In manners crude, in temper haughty / Thankless to parents, liars, swearers / Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers / I left a long, black, birchen rod / Such as the dread command of GOD / Directs a Parent’s hand to use / When virtue’s path his sons refuse.”

Take that, you swearers and base tale-bearers.

The influential, uncredited poem, “Old Santeclaus With Much Delight” — aren’t you lovin’ this old-timey language? — was published in a book with the wordy title “The Children’s Friend: A New-Year’s Present, to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve” (1821, William B. Gilley). It introduced vital aspects of the Santa Claus character that survive to this day, in the form of likewise uncredited illustrations reproduced via early use of lithography.

For the first time, Santeclaus is shown in a sleigh pulled by a reindeer. (The sleigh is marked, in large letters, “REWARDS.”) Though this Sante is bearded and wearing red, he bears little physical resemblance to the later popular ideal of the character. Santeclaus’ beard is brown, and he wears a tall “cossack”-style hat. The poem also places Santeclaus’ activities on Christmas Eve (as opposed to Dec. 6, the feast of St. Nicholas) for the first time.

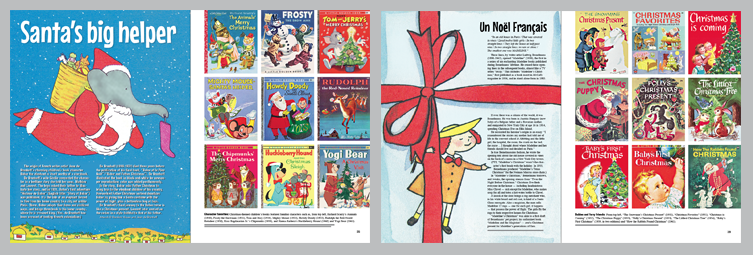

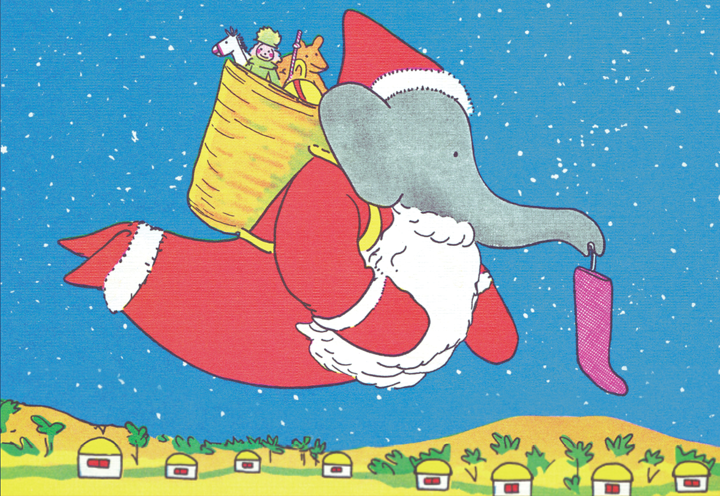

‘Babar and Father Christmas’ (1940)

The origin of French writer-artist Jean de Brunhoff’s charming children’s book character Babar the elephant is itself worthy of a storybook.

De Brunhoff’s wife Cécile concocted the character in a bedtime story she told her sons, Mathieu and Laurent. The boys asked their father to illustrate her story, and in 1931, Babar’s first adventure “Histoire de Babar” (English title: “Story of Babar”) was published. It’s the tale of an elephant forced to flee from his home country to a city not unlike Paris. There, Babar adopts fine dress and civilized ways, and brings them back to his home country, where he is crowned king. (Yes, de Brunhoff has been accused of touting French colonialism.)

De Brunhoff (1899-1937) died three years before the publication of his final book, “Babar et le Père Noël” (“Babar and Father Christmas”). De Brunhoff illustrated the book in black-and-white for newspaper reproduction; color was added posthumously.

In the story, Babar asks Father Christmas to bring toys to the elephant children of his country. Overworked Father Christmas instead deputizes Babar by giving him a Santa costume with the power of flight, plus a bottomless bag of toys.

De Brunhoff’s final journey to the Babar-verse is like a Christmas miracle.

‘Madeline’s Christmas’ (1956)

“In an old house in Paris / That was covered in vines / Lived twelve little girls / In two straight lines / They left the house at half-past nine / In two straight lines, in rain or shine / The smallest one was MADELINE.”

These lines, by writer-artist Ludwig Bemelmans (1898-1962), opened “Madeline” (1939), the first in a series of six enchanting Madeline books published during Bemelmans’ lifetime. He reused these opening lines in the subsequent books, almost like a TV series “recap.” This includes “Madeline’s Christmas,” first published as a book insert in McCalls magazine in 1956, and in stand-alone form in 1985.

If ever there was a citizen of the world, it was Bemelmans. He was born in Austria-Hungary (now Italy) of a Belgian father and a Bavarian mother, and emigrated to New York City at age 16 in 1914, spending Christmas Eve on Ellis Island.

In “Madeline’s Christmas,” Bemelmans borrows, and tweaks, the opening stanzas from “Twas the Night Before Christmas.” Christmas Eve finds everyone in the house — including headmistress Miss Clavel — sick except for Madeline, who makes soup for all and totes a hot-water bottle to Clavel.

A knock at the door brings a rug merchant who, in his white beard and red coat, is kind of a Santa Claus surrogate. Also a magician, the man sells Madeline 12 rugs — one for each girl, it happens — that possess the power of flight. The girls fly the rugs to their respective homes for Christmas.

“Madeline’s Christmas” was akin to a first draft of Bemelmans’ pet project, his unfinished book “Madeline and the Magician” — and a Christmas present for Madeline’s generations of fans.

‘How the Grinch Stole Christmas’ (1957)

There’s no denying it: The Grinch is Scrooge.

But “A Christmas Carol” can get pretty morbid — all that death, all those ghosts, all that talk of boiling people in pudding.

For little ones, a children’s book like Dr. Seuss’ “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” is less likely to inflict trauma. It has a hissable villain with a monster-ish visage, but no inhabitants of Who-ville are killed. Nor is their Christmas spirit.

“How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” — published by Random House in December 1957 — was written and illustrated by Theodor Geisel (1904-1991), better known by his pen name, Dr. Seuss. “The Grinch” was the 19th of more than 60 books published by Geisel, which include “The Cat in the Hat,” “Horton Hears a Who!” and “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.”

In Geisel’s trademark sing-song verse and fluid cartooning, he tells the story of a holiday-hating sociopath isolated in the snowbound mountains above the village of Who-ville, where inhabitants gleefully immerse themselves in the holiday. The Grinch plots to “steal” Christmas from the Whos by disguising himself as Santa Claus and absconding with their decorations, gifts and food during their Christmas Eve slumber.

So who was the Grinch, really — aside from Scrooge, of course?

There’s evidence that Geisel himself was the inspiration for his own character. In the book, the titular villain says of the Whos’ noisy revelry: “Why, for fifty-three years I’ve put up with it now!” One guess how old Geisel was when he wrote that line.

And here’s a fun fact: Geisel’s car vanity license plates read, not “CATHAT” or “HORTON” or “1FISH2,” but “GRINCH.”

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.