Following are excerpts from “Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships July 31).

‘Marvel Super Heroes’

It was the comic books come to life. And that ain’t hyperbole.

Grantray-Lawrence Animation’s series “Marvel Super Heroes” debuted in syndication on Sept. 5, 1966, a period during which superheroes could do no wrong — something the series put to the test. This was limited animation at its most limited. Actual Marvel page art was Xeroxed (then a new technology). Camera tricks such as zoom-ins were employed to give the illusion of movement. But lest we forget: This was artwork by Jack Kirby, Don Heck, Gene Colan, Bill Everett — guys whose illustrations had movement. The series’ roster of heroes comprised Captain America, the Sub-Mariner, the Hulk, Thor and Iron Man. But the shorts also introduced deeper-cut Marvel characters (to mainstream viewers, at least) such as the Avengers, the X-Men and many villains.

When I brought up the series to Marvel Comics legend Stan Lee in 1992, I found myself being serenaded. Lee warbled the first line from the show’s opening theme song: “He’s a sulky, over bulky, kind of hulky superhero …”

I told Lee that, believe it or not, I felt the 1966 cartoon series was the most successful attempt to capture Marvel on film up to that time. But how was it arranged that the actual Marvel Comics page art would be used?

“I don’t remember too clearly,” Lee said. “The two guys who did it, I believe, were (animators) Bob Lawrence and Steve Krantz. They were both interested in preserving the real feeling the Marvel characters had, and I worked with them. While the animation was rather limited at that time, they made a concerted effort to keep them as close to the stories in the Marvel comic books and as close to the artwork as possible.

“You’re quite right. Of everything that’s been done, those primitive little cartoons were the closest to our own style.”

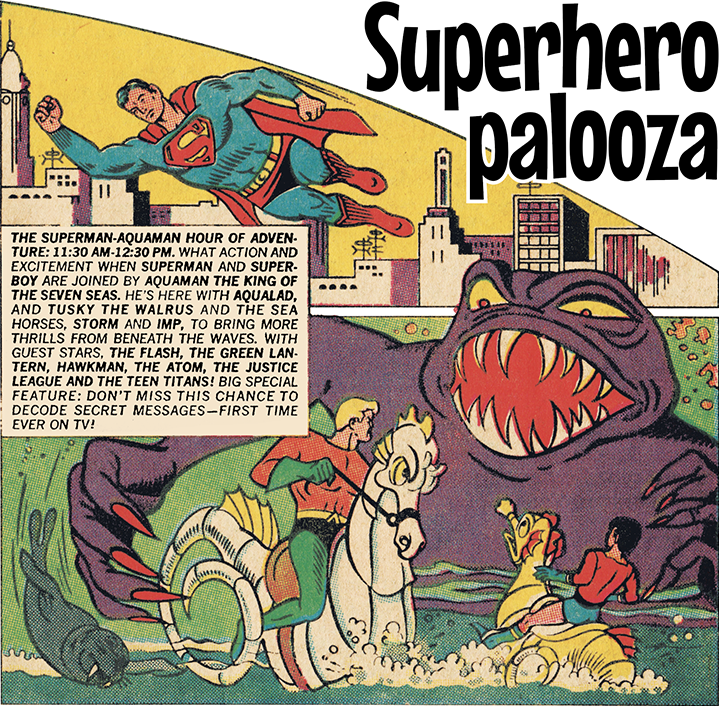

‘Superman/Aquaman’

“The Superman/Aquaman Hour of Adventure” from Filmation did for DC Comics what “The Marvel Super Heroes” did for Marvel: introduce a bunch of “new” characters to the mainstream. Besides the Superman and Aquaman segments, the show presented “guest” segments featuring Green Lantern, Flash, Hawkman, the Atom, Teen Titans, and the Justice League of America. (Wonder Girl was in the Titans, but Wonder Woman was not in the JLA.) Save for Superman, this was the first time any of these characters appeared on film, animated or otherwise.

We were accustomed to the Superman segments after a year of Filmation’s earlier “The New Adventures of Superman.” But the Aquaman segments seemed different, fresh. Filmation’s animation shortcuts smacked of ingenuity rather than desperation. The stories weren’t set in Metropolis or outer space; the undersea environment (augmented with the occasional use of a “wave” filter) was dreamlike.

“The Marvel Super Heroes” and “The Superman/Aquaman Hour of Adventure” felt like watershed moments, even to a dopey, insignificant child. The comic books we’d started reading in the wake of the TV “Batman” — these strange new worlds we were discovering — were suddenly coming to life on television. And kids all over American were entering into a fierce debate: DC or Marvel? Importance-wise, it was right up there with Beatles or Stones? Coke or Pepsi? Ginger or Mary Ann?

‘Space Ghost’

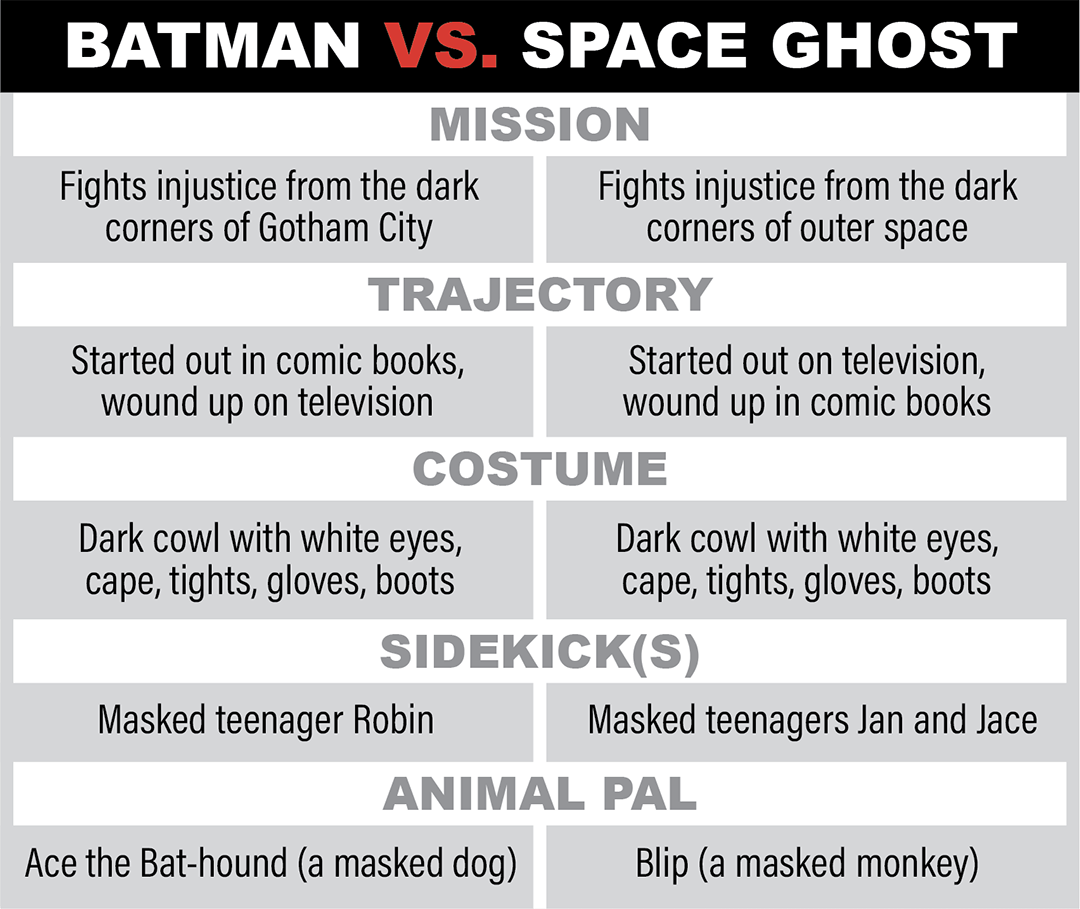

Despite having a masked monkey for a sidekick and some inherently goofy villains, Hanna-Barbera’s “Space Ghost” (initially broadcast 1966-68) played it straight, more or less.

Space Ghost has often been called, in elevator-pitch fashion, “Batman in space.” He certainly looks as cool as Batman. Much credit for this goes to Alexander “Alex” Toth (1928-2006), a comic book artist with a resumé dating back to the 1940s.

Toth pulled a mid-career switch beginning in 1960 by honing a specialty in character design and storyboarding for animation. Drawing on his extensive background in superhero comics — Toth had drawn Green Lantern, Flash, and the Justice Society of America during the Golden Age of Comics — he created sleek animation designs that were instantly classic. Toth rendered Space Ghost as a mysterious figure in a black hood (with white eyes), a gold cape, white tights and red armbands.

Toth pulled a mid-career switch beginning in 1960 by honing a specialty in character design and storyboarding for animation. Drawing on his extensive background in superhero comics — Toth had drawn Green Lantern, Flash, and the Justice Society of America during the Golden Age of Comics — he created sleek animation designs that were instantly classic. Toth rendered Space Ghost as a mysterious figure in a black hood (with white eyes), a gold cape, white tights and red armbands.

The character’s founding voice artist was Gary Owens, remembered as the announcer on the very ’60s TV comedy “Laugh-In.” Space Ghost patrolled outer space in his rocket plane, the Phantom Cruiser, accompanied by teenage cohorts Jan (voiced by Ginny Tyler of Disney fame) and Jace (Tim Matheson of “Animal House” fame), plus Blip the monkey (Don Messick, the voice of Scooby Doo). In keeping with the All Things Superhero policies of 1966, each of these characters was masked. Even Blip.

But was Space Ghost a ghost? Important details like Space Ghost’s origin story were left to subsequent iterations to fill in, and liberties were taken. In 1994, Space Ghost was reintroduced as a talk show host in the Cartoon Network’s droll sendup “Space Ghost: Coast to Coast.” The roster of live-action guests was, to say the least, eclectic. Guests included Bjork, Willie Nelson, the Bee Gees, the Ramones, Jim Carrey, George Clinton, Ice-T, Carol Channing, David Byrne, Kevin Smith, Charlton Heston, Timothy Leary, and — in yet another full-circle moment — Adam West.

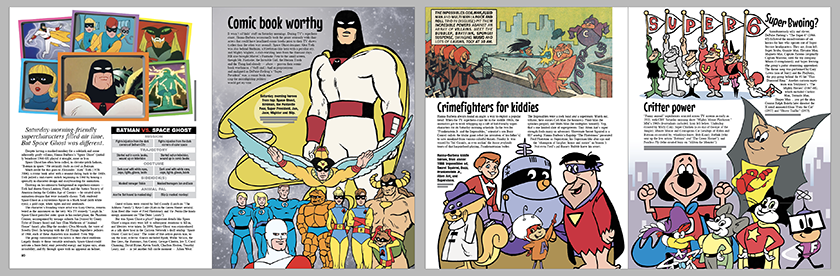

Comic book worthy

It wasn’t all kids’ stuff on Saturday mornings. During TV’s superhero craze, Hanna-Barbera occasionally took the genre seriously with characters that could have headlined comic books prior to their TV shows (rather than the other way around). Space Ghost designer Toth was also behind Birdman, a Hawkman-like hero with a peculiar cry, and Mighty Mightor, a club-wielding hero from the dinosaur days. HB also brought Marvel’s Fantastic Four to the small screen, though Mr. Fantastic, the Invisible Girl, the Human Torch and the Thing had already — ahem — proven their comic book worthiness. (’Nuff said.) And as preposterous and maligned as DePatie-Freleng’s “Super President” was, a comic book starring the moonlighting politico would get my vote.

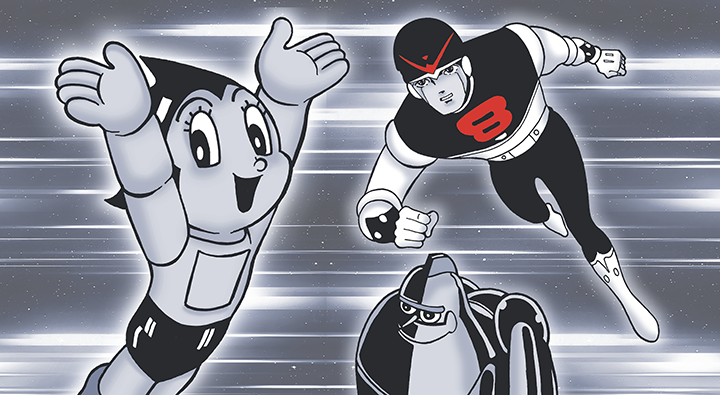

Japanimation

From manga — Japanese comic books that are read from back to front — came three superhero animated series imports that were super fun … and super weird. The print serial Tetsuwan-Atomu (1952-68) by revered writer-artist Osamu Tezuka was adapted by Japan’s Fuji TV as an animated series (1963-66) that was immediately exported to American TV as the heartwarming black-and-white wonder “Astro Boy” (1963-65).

The title character’s origin, as set forth in Episode 1, has a touch of “Pinocchio,” a trace of “Frankenstein.” He begins life as a human being named Aston Boynton. (Get it? Sounds like Astro Boy?) Aston dies in a car crash in the far-off, futuristic year 2000. (It was, ahem, a self-driving car.) Aston’s scientist papa, who wears an Eraserhead hairstyle, builds Astro Boy as a replacement for his son. The hitch: Astro Boy cannot grow up like other boys. Things get Shakespearean. Cries Astro Boy: “You’ve always told me that you love me as though I’m your very own flesh and blood!” Retorts his “dad”: “Flesh and blood? Why, that’s a joke, son!”

The manga format also yielded 8 Man (1963-66) by artist Jiro Kuwata and writer Kazumasa Hirai. (Kuwata illustrated some of Japan’s insane Batman manga.) As with Astro Boy, 8 Man was made into a black-and-white animated series (1963-64), which was dubbed into English as “8th Man” (1965). In the origin story, the life essence of a detective killed in the line of duty is transferred into a robot body. (You’re a thief, RoboCop!) In his secret identity, 8th Man has a girlfriend who doesn’t know he is a robot. (How does that work?)

“Gigantor” (1963) adapted artist Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s manga series of 1956. The animated show was dubbed into English for American television in 1966. It is one of three, count ’em, three TV shows from the period about a boy who controls a giant robot via remote control. (The other two: “Johnny Sokko and His Flying Robot” and “Frankenstein Jr.”)

Pre-order at TwoMorrows | Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Target | Previews World

See 62-page preview HERE

Read 13th Dimension’s preview HERE