Following are excerpts from “Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships Nov. 4).

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.

‘The Honeymooners’ (1955)

More than any other TV show — or movie, for that matter — “The Honeymooners” Christmas episode, which is mostly set on Christmas Eve, makes the viewer feel like it actually is Christmas Eve. Those who watched the original performance live (on stage in New York City and in living rooms across America) were literally seeing it on Dec. 24th.

It has something to do with the intimacy of the live audience … it is a living, breathing, laughing, coughing organism … the laughter is the opposite of “canned” … some gags hang on the precarious thread of audience recognition … but the audience melds with the players as another cast member … it’s almost mystical …

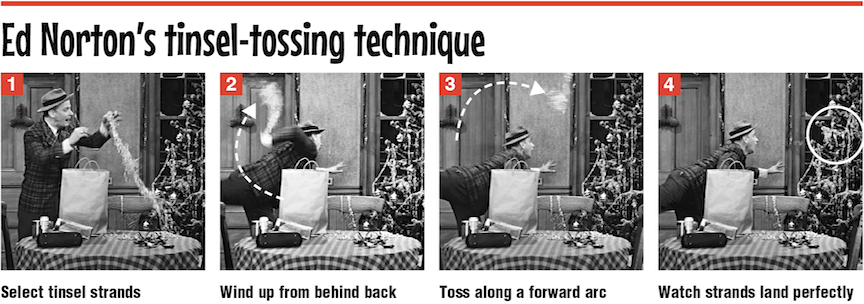

“The Honeymooners” — starring Jackie Gleason as everyschlub Ralph Kramden, a Brooklyn bus driver with big ideas and a waistline to match — began in 1951 as a recurring skit on the Gleason-hosted “Cavalcade of Stars.” The show is best remembered for its so-called “Classic 39” episodes (1955-56), which co-starred Audrey Meadows as Ralph’s long-suffering wife Alice; Art Carney as dimwitted sewer worker Ed Norton; and Joyce Randolph as Trixie, Ed’s wife and Alice’s sounding board.

Ralph and Alice live in a tiny Bensonhurst flat amid worn furniture and ancient facilities. There is love in this household, but the couple squabbles, often about money. During these arguments, Alice — lovely and petite to Ralph’s big and blustery — stands her ground, eyes flashing and hands on her apron-clad hips.

The Classic 39 are noted for their play-like feel and realistic quality. “The Honeymooners” is undoubtedly a show that solidified the situation comedy form. Many critics and fans point to it as the greatest sitcom in the medium of television.

In the Christmas episode, the four-person company is joined by only two guest actors. Together, they enact the simple tale of a gift-exchanging fiasco involving deception, near misses, a bit of slapstick, self-reflection, regret and, ultimately, forgiveness. There’s an O Henry-esque twist, a stirring soliloquy by Ralph on the spirit of Christmas, and an unprecedented (for the series) breaking of the fourth wall. All in under 30 minutes.

‘The Twilight Zone’ (1960)

In an alternate cinematic universe, “Miracle on 34th Street” might have followed the exploits of that drunken, slurring, flask-wielding Santa at the beginning of the film, rather than the perfect Santa who castigates him.

Rod Serling — creator, host, and main writer of the fantasy anthology series “The Twilight Zone” (1959-64) — went there, kind of. Serling’s thoughtful Christmas episode, “The Night of the Meek,” is often dark, occasionally funny, and explores themes of alcoholic despair and Dickensian poverty.

Art Carney — then known as a comedic actor for his role of Ed Norton on “The Honeymooners” — was afforded a dramatic stretch as Henry Corwin, the world’s least likely department-store Santa Claus. And Carney ran with it.

From the look of Henry, it’s a wonder he ever got hired. His beard and costume are filthy. And this unlaundered, unshowered, unloved man probably stinks somethin’ awful.

We first see Henry, in costume, downing shots at a sleazy dive. When neighborhood kids peer into the window, Henry laments, “Why isn’t there a real Santa, for kids like that?” Replies the burly bartender (Val Avery): “You know what your trouble is, Corwin? You let that dopey red suit go to your head.”

Henry arrives at the store late to a crowd of antsy shoppers, and promptly falls on his face. “Look, Mom, Santa Claus is loaded!” a boy exclaims. Henry is fired by his boss, Mr. Dundee (John Fiedler), but doesn’t leave without imparting a farewell speech.

Nearly in tears, Henry says of the boy’s mother: “Someone should remind her that Christmas is more than barging up and down department-store aisles, pushing people out of the way.” He speaks of poor souls for whom “the only thing that comes down the chimney on Christmas Eve is more poverty.”

Then comes the “Twilight Zone” twist.

‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ (1964)

What is “Rudoph” about, really?

Is it about one foggy Christmas Eve, when Santa asks a reindeer with a nose so bright to “guide my sleigh tonight?”

The true answer is as plain as the (red) nose on Rudolph’s face.

Rankin/Bass’ 1964 TV special “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” is about outcasts — the ostracized, the isolated, the bullied, the ridiculed, and even the self-loathing.

But the puppet-animation special calls them a word that is a bit more child-friendly: “misfits.” (This was an early instance of “owning” a pejorative in order to weaken its effect.)

As for the misfits in the TV special: There’s Rudolph, whose “non-conformity” gets him kicked out of reindeer games, forbid- den to see his girlfriend, and banished from Santa’s sleigh team. There’s Hermey, an elf who would rather be a dentist than a toymaker, and is told by his boss, “You’ll never fit in.”

And then there’s an entire island of misfits. It’s called, a-hem, the Island of Misfit Toys.

In a masterstroke, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” places Santa Claus — the jolliest, most toy-givingest guy on the planet — on the wrong side of history. Santa is (gasp!) one of the haters.

So if you were a child who didn’t quite fit in, “Rudolph” had your back.

‘A Charlie Brown Christmas’ (1965)

“I think there must be something wrong with me, Linus. Christmas is coming, but I’m not happy. I don’t feel the way I’m supposed to feel.”

So says Charlie Brown to Linus, in the first words spoken in “A Charlie Brown Christmas” — a sign, right off the bat, that this Christmas TV special was going to shatter some norms.

Did any prior Christmas special explore the theme of holiday depression? For that matter, did any Christmas special before, or since, name-drop hypengyophobia, ailurophasia, climacophobia, thalassophobia, gephyrobia and pantophobia?

Not that the producer, director, sponsor and writer-artist behind the first special based on the comic strip “Peanuts” were patting themselves on the back once the special was completed. Quite the opposite. The men were convinced they had a bomb on their hands.

The rest of the world would think differently.

“Peanuts” creator Charles M. Schulz on how the holidays can be a sad time for some people: “I suppose it has something to do with our inability to rise to the occasion. We see TV shows and movies and magazine articles and wonderful photographs of people having a great time, and it simply isn’t true. Most of the time, our lives don’t live up to those expectations. There are a lot of lonely people.”

‘How the Grinch Stole Christmas’ (1966)

Chuck Jones kept asking Theodor Geisel to let him make a TV special out of Geisel’s 1957 book “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss, kept saying no.

It’s not like Geisel wasn’t aware of Jones’ many accomplishments in the field of animation. Jones (1912-2002) was a driving force behind Warner Bros.’ “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” animated shorts featuring Bugs Bunny and cohorts.

It also wasn’t like Geisel hadn’t already known Jones as a collaborator. During the years of World War II, the two men partnered on 11 out of 26 “Private Snafu” cartoon training films made between 1943 and 1955, with Jones as director and Geisel as writer.

But Jones finally wore Geisel down, and we are the richer for it.

The 1966 animated special “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” — written by Geisel, directed by Jones — accomplished two seemingly disparate things at once. It was wholly true to Geisel’s 1957 book. And it was a marked departure from same.

First on Jones’ itinerary was to flesh out the book to accommodate the special’s running time. He called upon Geisel to make additions to the book’s “script” in the form of extra verses, names for the Whos’ toys, and lyrics for three songs.

It then fell to Jones to create animation-friendly character designs and — the most significant liberty of all — add color to Geisel’s intrinsically black-and-white world. Jones’ Who-ville is practically psychedelic.

Casting horror-movie star Boris Karloff as the narrator (and the voice of the Grinch) was an inspiration. The Grinch is unrepentantly evil; he’s a bigot (he hates Whos for being Whos); treats his dog Max more like a slave than a pet; and steals candy from babies. Karloff played some diabolical characters in his career, but the Grinch can stand alongside Hjalmar Poelzig, Mord the executioner and the Wurdulak.

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.