‘Promise, no tears’: The Duke’s final ride

By Mark Voger, author, “Monster Mash: The Creepy, Kooky Monster Craze in America 1957-1972″

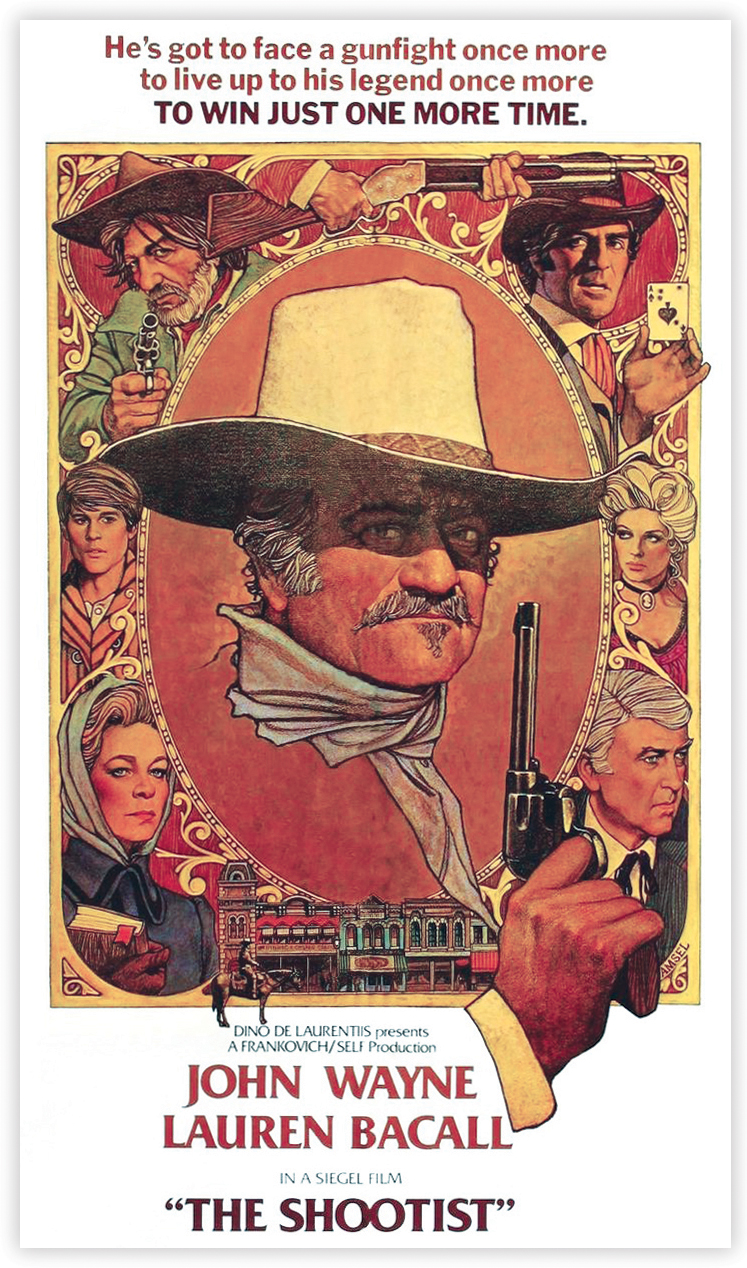

For fans of John Wayne, his final film “The Shootist” is a miracle.

Think about it. His last movie could have been “Brannigan.”

But somebody up there liked ol’ Duke — and especially ol’ Duke’s fans — and gave us Don Siegel’s “The Shootist,” a thoughtfully written, acted and directed film with a moving performance by Wayne and a cast straight outta Hollywood Heaven.

Mind you, “The Shootist” was a tough shoot for its star and its director.

Filming was a constant tug-of-war between Wayne and Siegel. Wayne was ill, impatient, and questioned many of Siegel’s calls. Wayne especially thought Siegel asked for too much “coverage” — that is, extra takes of a given scene.

(When Batjac, Wayne’s production company, made movies, they would settle for one take if it looked good enough. Batjac’s films often came in ahead of schedule and under budget.)

Wayne couldn’t understand why Siegel kept ordering more takes. It turns out, the old man was dead wrong.

Wayne’s performance in “The Shootist” is, I daresay, his best on film. The world doesn’t agree. Most fans and critics, if they care to discuss Wayne’s acting at all, point to his hard-hearted Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s “The Searchers” (1954).

But I choose “The Shootist” because in it, Wayne achieves pure poignancy. He makes every line of dialogue from this story about a gunfighter diagnosed with cancer sound like it’s coming from within. (Sometimes it is; cancer was all-too-familiar territory for the actor.)

And “The Shootist” is not so much a western as a human drama set in the last days of the Old West. There’s a climactic shootout, sure, but the movie is about little moments, not big guns.

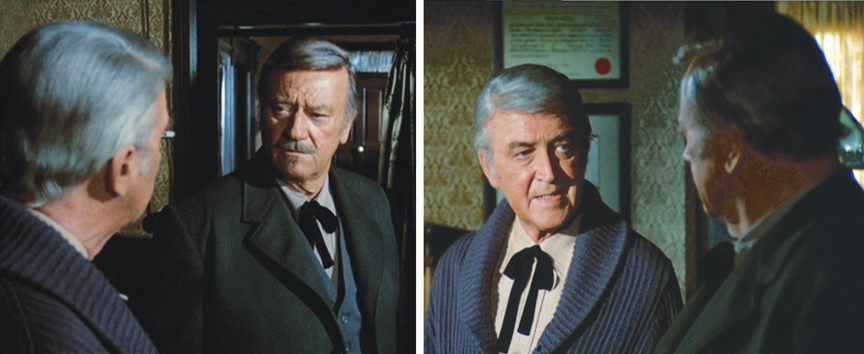

Synopsis: Famous gunslinger J.B. Books (Wayne) rides into Carson City to be examined by a medico he trusts, Dr. Hostetler (James Stewart, Wayne’s co-star in “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”). Hostetler confirms Books’ great fear: he has “a cancer.” Told he has maybe two months to live, Books decides to take a room at the boarding house of a widow, Mrs. Rogers (Lauren Bacall, Wayne’s co-star in “Blood Alley”). He’s already met her ornery son Gillom (Ron Howard) under less-than-cordial circumstances.

Books would prefer to keep his identity, and his diagnosis, to himself. But through various circumstances, it isn’t long before all of Carson City finds out that there is a dying celebrity in their midst — and some come swarming in for a payday.

These include an unsympathetic marshal (Harry Morgan), a shrewd stable boss (Scatman Crothers), an ambitious undertaker (John Carradine, one of Wayne’s co-stars in “Stagecoach”), a designing newspaperman (Rick Lenz) and an old flame (Sheree North).

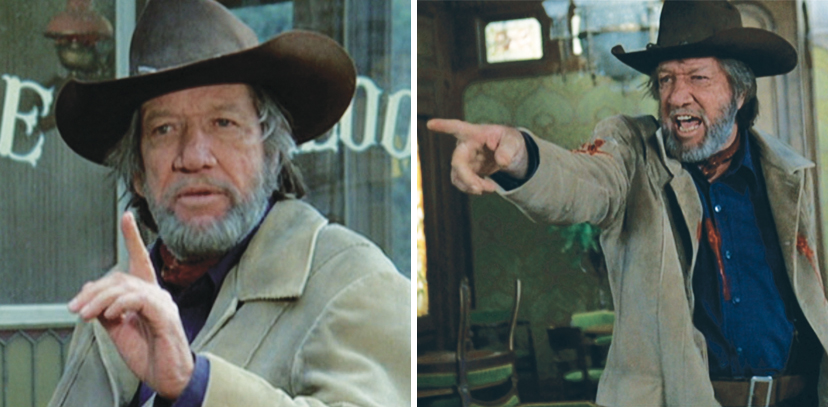

Three men are interested in besting the great J.B. Books in a shooting match: a deadshot faro dealer (Hugh O’Brien); the vengeance-bent brother (Richard Boone) of a previous Books opponent; and the world’s most psychopathic milkman (Bill McKinney).

But the crux of the movie is those aforementioned small moments, such as when Books and the widow Rogers call each other by their first names — he’s “John Bernard,” she’s “Bond” — in an affectionate way that feels like lovers exchanging pet names. Or how Books reacts when Hostetler delivers the bad news — a faraway look as he ponders death, and eventual acceptance. Or how Books becomes, just for a few days, a surrogate father to Gillom.

Or how John Bernard extracts a promise from Bond that there will be no questions, and no tears, when she sees him in his freshly cleaned Sunday-go-to-meetin’ suit on the next, fateful morning. Because, we know without being told, the great J.B. Books is fixin’ to die.

Wayne looks and acts tired in “The Shootist” — as he certainly was in real life — but it plays to the material beautifully. J.B. Books, like the actor who plays him, is a “tuckered out” old man. But, as Books tells his old flame when she proposes a quickie wedding so she can profit from his death, “I still have some pride.”

Books’ credo seems like that of the icon that Wayne played onscreen for five decades: “I won’t be wronged, I won’t be insulted, and I won’t be laid a hand on. I don’t do these things to other people, and I expect the same from them.”