Like the video films we saw

After David Bowie’s “BlackStar” video came “Lazarus.” No more videos will come, with the possible exception of lovingly edited posthumous ones. Those can be nice, but they don’t really count. From a performer whose bread and butter was always rock — but one who was truly a multimedia artist and a willing adopter of the music-video format — “Lazarus” is the final work.

Like “BlackStar,” “Lazarus” has moments that are heartbreaking, hilarious, rocking and deeply significant. The video reflects Bowie’s contemplation of death in his final months. (Reportedly, the week “Lazarus” was shot, Bowie was informed his condition was terminal, and treatment was discontinued.)

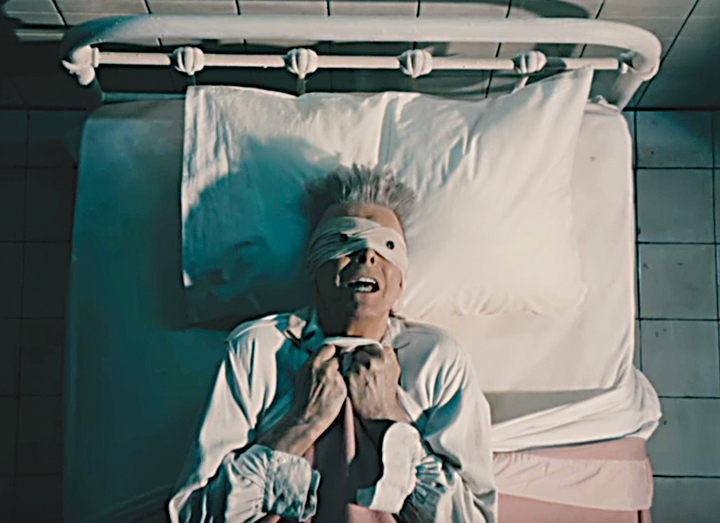

The first time we see Bowie in “Lazarus,” it’s a shock, like when you visit a loved one in the hospital who you haven’t seen for a while, and you were unaware of how much this person’s condition deteriorated.

The first time we see Bowie in “Lazarus,” it’s a shock, like when you visit a loved one in the hospital who you haven’t seen for a while, and you were unaware of how much this person’s condition deteriorated.

Bowie sings from a hospital bed — no beating around the bush here — wearing the same “Button Eyes” bandages from “BlackStar.” His hands are, if you’ll pardon the graphic description, veiny and purple. He looks like a flailing prisoner of illness as he sings, “Look up here, I’m in Heaven / I have scars that can’t be seen.”

A theme of the video seems to be lucidity. Bowie’s character is confused by drugs (“I’m so high it makes my brain whirl”) and his understandably haywire emotions.

But, as with “BlackStar,” “Lazarus” has a lucid “rock star” passage. In “BlackStar,” the strutting David Bowie of old rematerialized for two full verses. In “Lazarus,” he comes back for only one lyric, “By the time I got to New York, I was living like a king,” which he sings with a joyful smile, looking directly at us. Our hearts are warmed, but only fleetingly.

But, as with “BlackStar,” “Lazarus” has a lucid “rock star” passage. In “BlackStar,” the strutting David Bowie of old rematerialized for two full verses. In “Lazarus,” he comes back for only one lyric, “By the time I got to New York, I was living like a king,” which he sings with a joyful smile, looking directly at us. Our hearts are warmed, but only fleetingly.

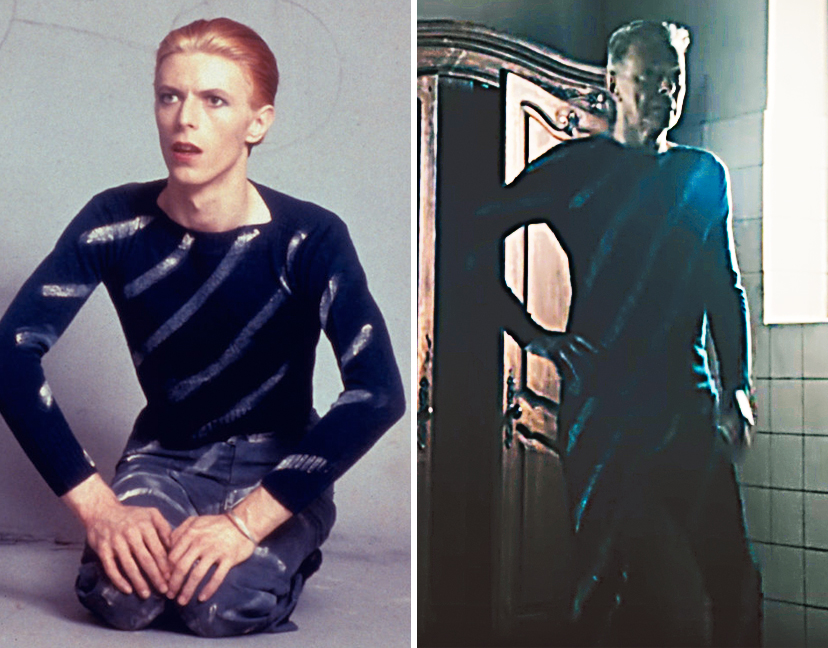

The character suddenly drifts into bewilderment and lament, both in Bowie’s lyrics and his pantomime. Wearing the same diagonal-striped costume he posed in during a 1974 session with photographer Steve Schapiro, Bowie looks tired and frail where he was once appeared vital and invincible. The stark contrast is quite intentional.

The character suddenly drifts into bewilderment and lament, both in Bowie’s lyrics and his pantomime. Wearing the same diagonal-striped costume he posed in during a 1974 session with photographer Steve Schapiro, Bowie looks tired and frail where he was once appeared vital and invincible. The stark contrast is quite intentional.

Bowie’s not finished yet. This persona, his last, then sits at a desk adorned with the jeweled skull from “BlackStar,” and writes. In my interpretation, he is writing his memoirs. Alas, he’s begun them too late. Death is rapping at his chamber door as he struggles in vain to remember his life and put it down on paper.

Bowie’s not finished yet. This persona, his last, then sits at a desk adorned with the jeweled skull from “BlackStar,” and writes. In my interpretation, he is writing his memoirs. Alas, he’s begun them too late. Death is rapping at his chamber door as he struggles in vain to remember his life and put it down on paper.

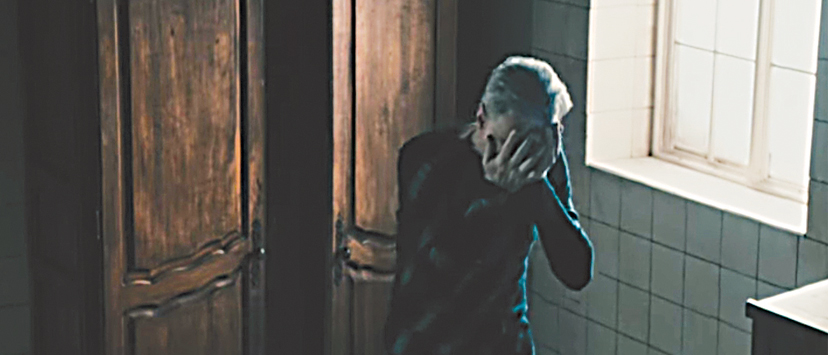

Finally, the character accepts the inevitable. Bowie’s face drops into a resigned expression, and he backs into a chifforobe that represents the portal between life and death. As he shuffles backward, he is as determined as ever. Only this time, it’s to die.

Finally, the character accepts the inevitable. Bowie’s face drops into a resigned expression, and he backs into a chifforobe that represents the portal between life and death. As he shuffles backward, he is as determined as ever. Only this time, it’s to die.

THE VIDEO