‘Mummy’ beauty Zita Johann’s daring followup

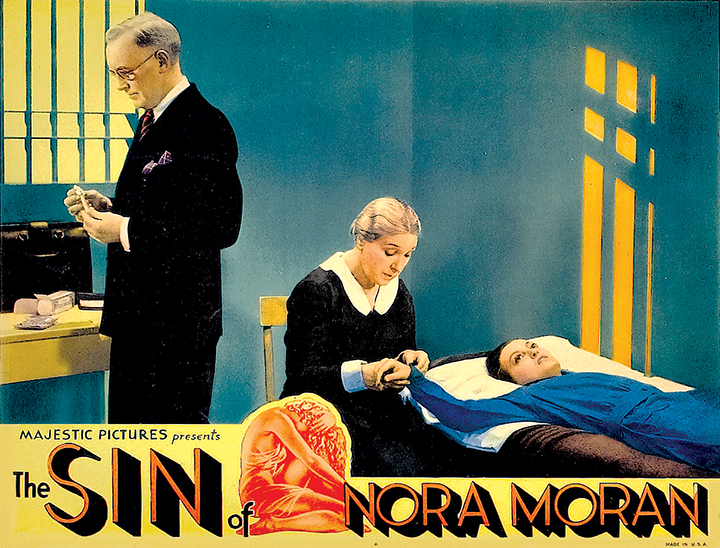

‘The Sin of Nora Moran’

The Film Detective

$24.99 (Blu-ray) and $19.99 (DVD)

65 minutes with 20 minutes of special features

Not rated

By Mark Voger, author

“Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture”

The little-known, largely unseen, low-budget curiosity “The Sin of Nora Moran” (1933) is not a horror film. But aficionados of vintage horror need to see it.

There’s one very good reason: Zita Johann.

She’s the unusual beauty with huge, magnetic eyes who, in Karl Freund‘s “The Mummy” (1932), embodied her role as a fashionable socialite possessed by an Egyptian princess. Ankh-es-en-amon may have died 3,000 years ago, but her lover Im-Ho-Tep (Boris Karloff) still carries the torch for her — literally and figuratively.

Phil Goldstone’s “Nora Moran” is a “pre-code” Hollywood film — that is, it was released prior to the enforcement of the infamous Hays Code, which ushered in a long period of prissy censorship among film studios. Like many movies from the immediate pre-code era, “Nora Moran” boasts surprisingly adult themes, and some daring visuals. The film is now available in a restored edition from The Film Detective.

Johann stars as the titular character who, after her adoptive parents are killed in a car accident, uses her modest inheritance to take dancing lessons. Nora’s dearest wish is to become a nightclub dancer, but when that dream fails to pan out, she joins a traveling circus. After she is sexually assaulted by a skeezy lion wrestler (John Miljan), Nora flees the circus.

She returns to the nightclub milieu, and this time lands a dancing gig. Nora is noticed by handsome, well-to-do Dick Crawford (Paul Cavanagh), who sweeps her off her feet, setting her up in a cozy cottage that he, of course, frequents. The snag: Unbeknownst to Nora, Dick is a married man who happens to be running for governor of a neighboring state, and whose brother-in-law John Grant (Alan Dinehart) is the district attorney hell-bent on avoiding scandal. When a dead body turns up in Nora’s living room, that seems like an impossibility.

You can almost call the film protofeminist. Long before Womens’ Liberation and the MeToo movement, “Nora Moran” explored how powerful, wealthy men can exploit young women — about how, when it suits them, these men can paint women as unworthy of fair consideration. The district attorney, for instance, assumes that Nora is a gold-digger. How wrong he is.

Earlier, I said that “Nora Moran” isn’t horror. But it is an existential fantasy at times. Most of the story is told in a kind of braided flashback, with shifting perspectives, dream sequences and what you might call “visions.” The film is notable for its creative camera movement and many inventive montages. And you can’t take your eyes off Johann, who looks ravishing and delivers an earnest performance, given the melodramatic material.

“The Film Detective’s” print, restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, looks pristine, especially considering the low-budget, “indie” origins of “The Sin of Nora Moran.” This level of scrubbing is usually reserved for better-known big-studio stuff. (“Nora Moran” was released by the short-lived “poverty row” outfit Majestic Pictures, the studio behind “The Vampire Bat” and “The World Gone Mad.”)

Included is a special feature narrated by Samuel M. Sherman about twists and turns leading to the rediscovery of “The Sin of Nora Moran.” Sherman is a looming figure in the cult film world, as a co-founder of Independent-International Pictures (“Satan’s Sadists,” “Dracula vs. Frankenstein”), and onetime editor of Screen Thrills Illustrated magazine (from Warren Publishing, the company that brought you Famous Monsters of Filmland). Sherman recounts how he obtained a print of “The Sin of Nora Moran” in the 1960s, befriended Johann, and coaxed her out of retirement to make a cameo in his 1986 horror cheapie “Raiders of the Living Dead.” (Although, from the looks of the footage shown, perhaps Johann would have been better off staying home that day.)

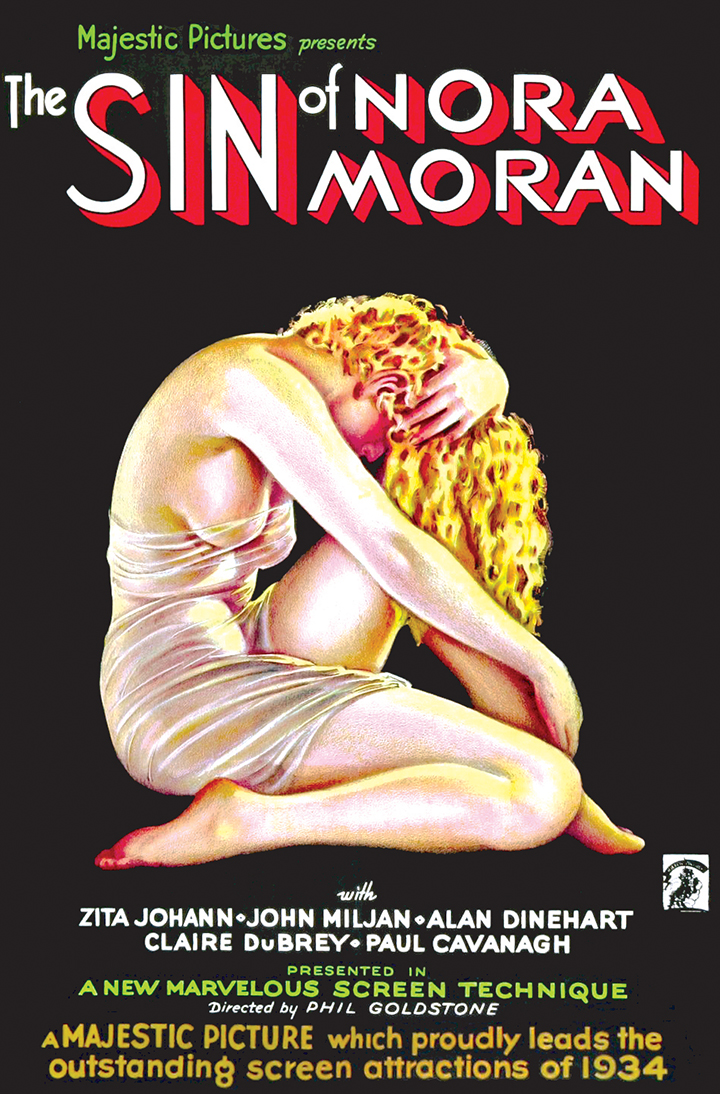

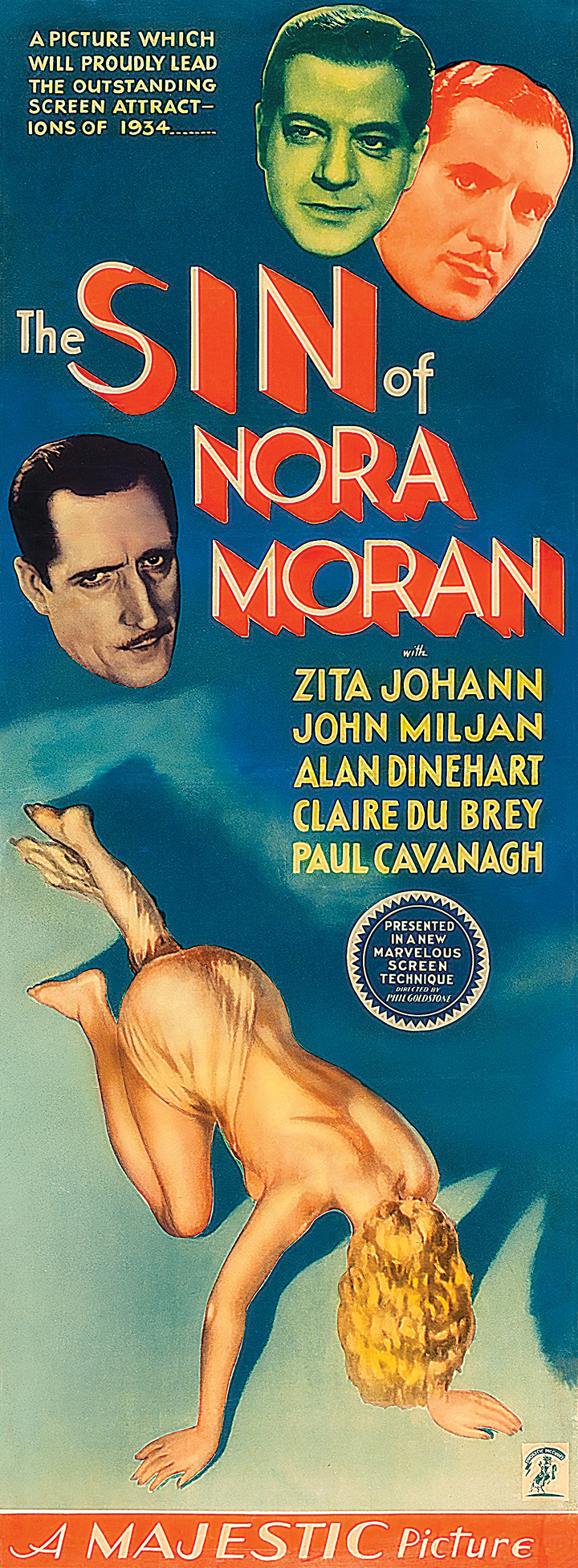

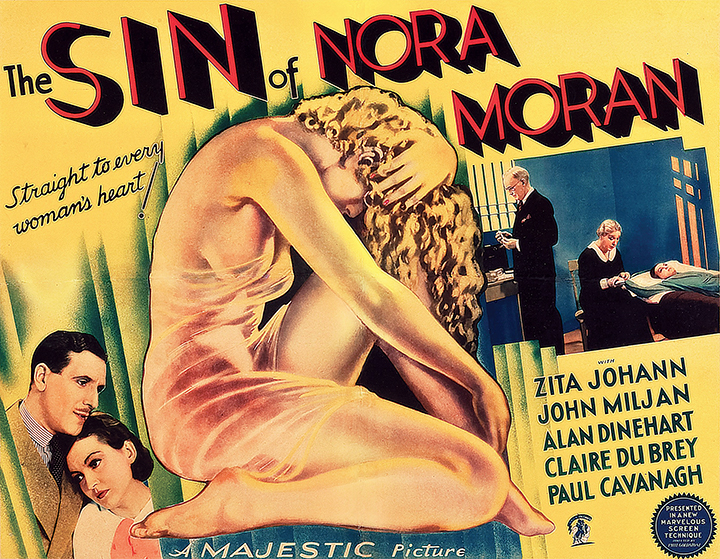

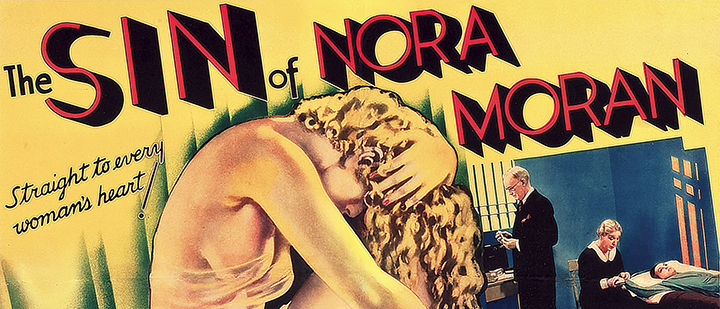

The Film Detective’s box art is derived from the movie poster by artist Alberto Vargas, later a mainstay of Playboy magazine. Along with the likes of Gil Elvgren and Enoch Bolles, Vargas was a master of the “pinup” — that is, paintings of sexy ladies in revealing outfits. (This was the time before Pornhub and Cardi B videos.) We have to be clear-eyed about Vargas’ artwork here. It doesn’t resemble Johann in the least (not that aficionados will complain). More to the point, you’d be hard-pressed to defend the poster as something that represents the film thematically. To be honest, Vargas’ illustration is transparent (no pun intended) titillation.

But what are movie posters for? (Answer: To sell movies.)

More about Zita Johann HERE.