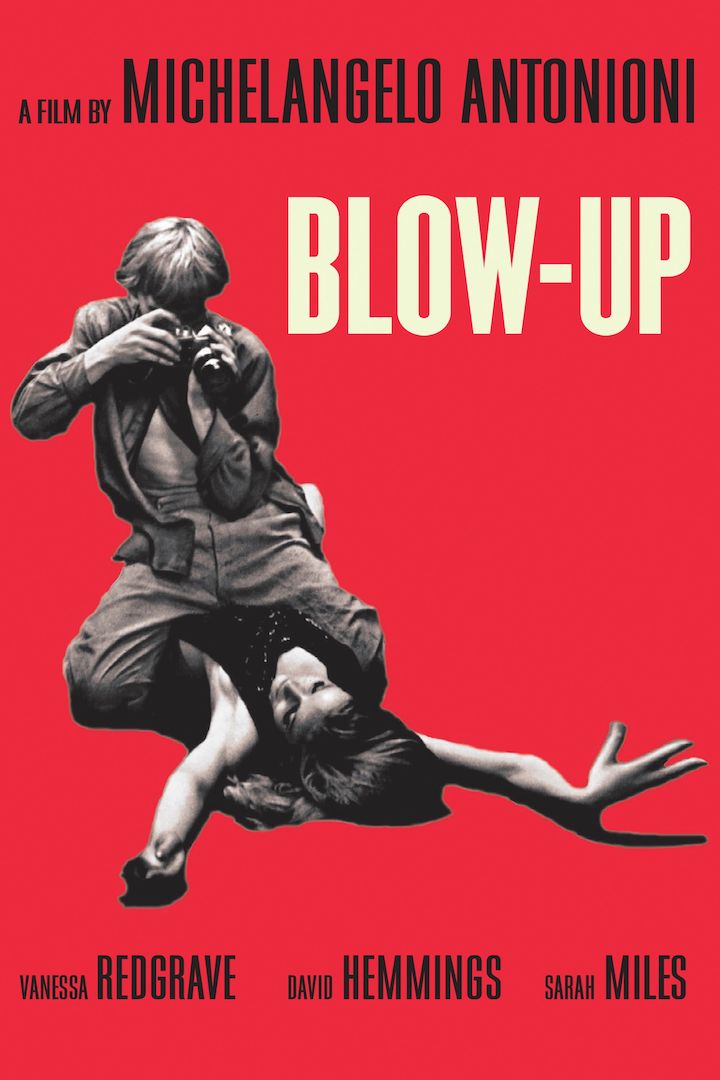

Antonioni: Stranger in a strange land

By Mark Voger, author

“Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture”

Rock ‘n’ rollers recall Michelangelo Antonio‘s “Blow-Up” for one reason, chiefly: It presents a performance by the Yardbirds, with two guitar giants of the period, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, trading licks. (Eric Clapton was also once in the Yardbirds, making this band a springboard for guitarists without equal.)

But there are other reasons to put “Blow-Up” on one’s watch list.

In his first English-language production, Antonioni crafted a film largely about voyeurism in which the director himself is very much a voyeur. Though Antonioni is always in control of what we see on the screen, he is a stranger in a strange land.

Strange, indeed. “Blow-Up” is akin to Alfred Hitchcock in its basic premise: A fashion photographer may or may not have captured a murder with his camera. You could almost picture Cary Grant or James Stewart in such a role. But Antonio sets “Blow-Up” in a modern milieu, what we now wistfully call “swinging London,” and he brings us as close as he can to the action — the clubs, the parties, the pretty people, the pot-smoking, the sex.

However, this is Antonioni, and anything he shows us must be filtered through his metaphorical lens. Take the Yardbirds sequence. The band’s audience is joyless and listless, if not catatonic, until Beck smashes a guitar, Who-style, and throws its remnants into their midst. The suddenly animated audience fights over the unsalvageable shards. This is largely interpreted as Antonio’s statement on disaffected youth. Whatever the symbolism, you would scarcely have found an audience of such sad zombies at a real-life Yardbirds show.

Synopsizing a movie with such a languid pace — and one that puts such a premium on visuals — is kind of missing the point, but here goes. “Blow-Up” follows an arrogant, unnamed photographer (David Hemmings) for whom life is a game. Hemmings uses affected charm and transactional coercion to get what he wants, both in his work and in his sexual pursuits. And he’s an unmitigated jerk. Though Hemmings is the film’s protagonist, it’s hard to love this guy.

His initial moments in the film usually go unnoticed by first-time viewers; Hemmings is among dozens of rough-looking, down-on-their-luck “sods” who grimly file out of a “doss house” (British-ese for a homeless shelter). Once out of sight of his fellow sods, he hops into a spiffy Silver Cloud III Rolls Royce convertible, stuffing a camera into the glove compartment. (It turns out he was surreptitiously shooting the old-timers for a book of photography that will tell their story — while exploiting them, of course.)

A colorful, somewhat annoying band of fun-loving mimes, who likely represent the rise of “flower power,” parade by. Though their stance is anti-establishment, they’re not above a spot of panhandling. Hemmings makes a contribution to the cause from his Rolls, and drives off.

Then comes the film’s most famous sequence, the Yardbirds notwithstanding: Hemmings photographs a sexy, slinky model (real-life model Veruschka). Put bluntly, the photo session is a pantomime coitus. Hemmings commands, cajoles and even kisses his model to get what he wants. (Mike Myers sent up the sequence to hilarious effect in his “Austin Powers” films.) Still shooting, Hemmings directs Veruschka to lay on her back, and then straddles her. Both are clothed, but the subtext is screaming out loud here.

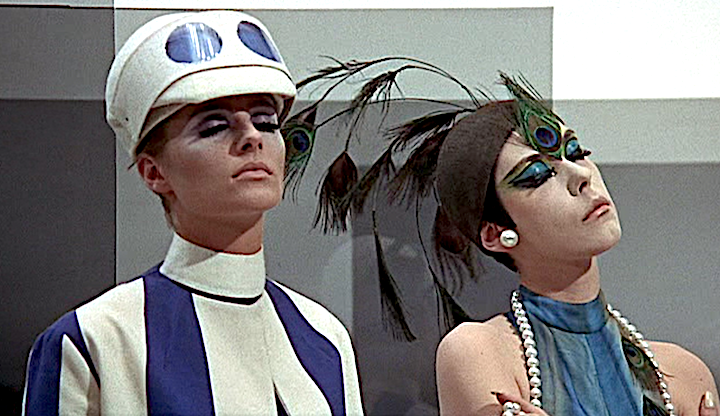

We watch Hemmings gallivant through his day: berating a group of models in supercool ’60s attire during another shoot; visiting an artist friend (John Castle) whose girlfriend (Sarah Miles) has feelings for him; slyly negotiating the purchase price of an antique store (real estate seems to be his side gig); spinning a web to ensnare two naive local girls (Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills) who are desperate to audition for him.

Finally, we come to the film’s Hitchcock moment. While absent-mindedly strolling through a park, Hemmings spots a couple who are, it appears, getting to know each other. She (Vanessa Redgrave) is 30-ish, he (Ronan O’Casey) is 50-ish. From a distance, Hemmings casually photographs them as they frolic, or seem to. Later, after developing the film, Hemmings comes to believes that his camera saw something his eyes did not.

Don’t expect a Hitchcockian resolution. Some have labeled “Blow-Up” an avant-garde film, but I wouldn’t go that far. It’s unconventional, but there is a narrative. Most of its information is doled out, not via exposition, but non-verbally. The film documents a place in time, and its mysteries grow more apparent, albeit ever so slightly, with each viewing. “Blow-Up” is a “journey” movie, not a “destination” movie, to be sure.

VIDEOS

Original 1966 trailer

Modeling sequence with Veruschka

Yardbirds sequence