Innovations in animation

Just watching a Fleischer Studios animated short — such as the ’30s-’40s Popeye, Betty Boop and Superman cartoons — one senses that something different, something innovative, was going on. A simple moment like the spinning Christmas tree in the Fleischers’ charmingly weird “Christmas Comes But Once a Year” (1936) is so inventive that a half-century later, it was still influencing animators who strove to advance 3D realism in the medium.

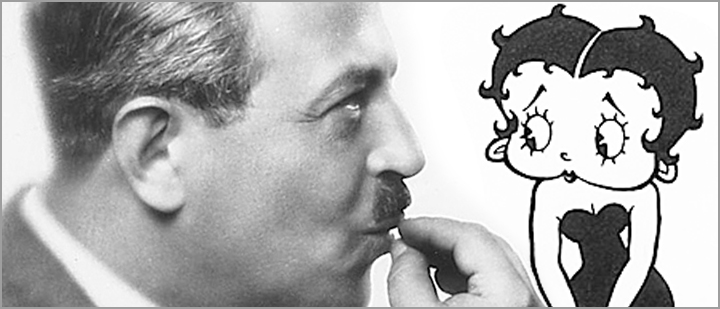

I recently corresponded with Cam MacMillan, an animator and author of the charming, decidedly Hawaiian children’s book “Pineapple Poet and the Curse of the Smoothie Man.” He told me I was mistaken when, in “Holly Jolly,” I wrote that the spinning Christmas tree was achieved via “rotoscoping” (tracing live-action frames to effect a 3D look), a process pioneered by studio head Max Fleischer. The truth is even better. I’ll let MacMillan explain.

“I took classical animation at Sheridan College, and was one of the originators of 3D character animation,” he wrote me. “So — rotoscoping was used by Fleischer back in the Betty Boop days; actually, they started with rotoscoping before they developed ‘keyframe’ animation. (Walt) Disney was always playing second fiddle to them technically, frequently making less-good cartoons while trying to figure out and imitate their work. If you compare what Fleischer was doing in 1934 to where Disney was, it’s obvious that Disney was way behind them.”

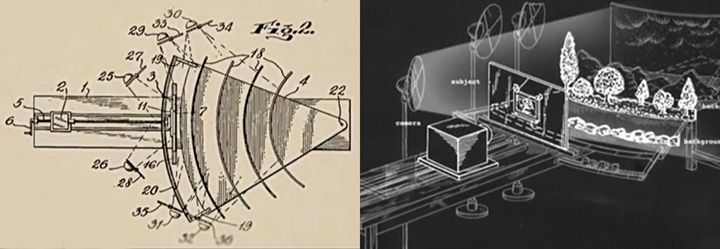

Continued MacMillan: “The animated Christmas tree you refer to was not an example of rotoscoping. Rather, it was an amazing example of their 3D rotating flatbed invention. The idea was simple and brilliant: just film the animation horizontally, not vertically, with the camera pointing straight out, instead of aiming down onto the artwork below it.

“The whole table could rotate — like the big circular tray in the middle of the table at a Chinese restaurant — allowing the background to move when the characters walk in any direction. The tabletop buildings were painted and constructed to match the cartooniness of the scene. We tried building one at school, and it was freakin’ difficult.”

Wow. MacMillan supplied some diagrams and videos to help explain the process.

“For the tree, they simply put a big sculpture of it at the center focal point, and spun it a 1/4-inch at a time per frame,” MacMillan wrote. “I’m really obsessed with the whole process, because we tried to crack how they did this and it led to all sorts of spin-off ideas, like mixing 3D and cel animation.”

MacMillan again: “Here is a video that goes into detail about how Fleischer did their 3D sets, but don’t blink. This was shot in their new Florida studios; they used to work in the Flatiron Building in New York, until that got a bit tight for them. The video shows how they shot horizontally, laying it all out flat, but then bringing it up in front of the camera on a giant hinge. I think this is the only surviving film of the (now lost) process.”

MacMillan also shared the above short, director Dave Fleischer‘s “Poor Cinderella” (1934), which MacMillan deems the best of the 3D Fleischers. “It’s a Betty Boop cartoon shot in two-strip color,” he wrote. “It’s a classic — sexy and hip, self-referential and incredibly well drawn. At the seven-minute point, Betty giggles and dances across a 3D set. The lighting here puts them in slightly darker shade that pushes the realism and romance of the scene. Using stage lighting techniques is something you can only do with these 3D sets.”

Above is “Christmas Comes But Once a Year,” also directed by Dave Fleischer. This the best print I’ve ever seen of the woefully under-remembered ‘toon. It should be on everyone’s holiday must-see list alongside “Charlie Brown,” “Rudolph” and “The Grinch.” The spinning Christmas tree is at 7:56.

Emulating the Fleischers

As for MacMillan and his cohorts’ attempts to emulate the Fleischers: “We tried to figure these 3D sets out when we were at the Sheridan School of Animation. Ric Sluiter, Joe Sherman and I were determined to make a full working 3D setup, but we finally sat down with pencil and paper, worked out the size and tools involved, and figured it would take us all summer, so screw it!

As for MacMillan and his cohorts’ attempts to emulate the Fleischers: “We tried to figure these 3D sets out when we were at the Sheridan School of Animation. Ric Sluiter, Joe Sherman and I were determined to make a full working 3D setup, but we finally sat down with pencil and paper, worked out the size and tools involved, and figured it would take us all summer, so screw it!

“Joe went on to use the technique in a few commercials made at Nelvana Studios in Toronto. Ric went on to be the layout director for Disney’s original ‘Mulan’ movie (1998), strangely enough at their Florida studios.

“I wrote and produced the last full animation that Fleischer animators Johnny Gent (Gentilella) and Earl James ever worked on: ‘Pot O’ Luck’ at the New York Institute of Technology. It was the first all-digital visual and soundtrack cartoon ever made. This would have been about 1985. Earl started on the black-and-white Betty Boops in the early 1930s in the Flatiron Building. I went to his wake.”

My thanks to Cam MacMillan. Find out more about his book, which was illustrated by Don Gauthier, HERE.

Post script

The video about the inner workings of Fleischer Studios made it clear that many women were employed at the facility. This was unusual for the 1930s, when sexist hiring practices were still rampant. It brought to mind something that has been a lifelong regret for me.

In 1998, I met a woman named Lorraine Thomas who had once been an “in-betweener” for Fleischer Studios. I was profiling her husband, Worth Thomas, then 87, for the Asbury Park Press. He was the artist who painted the iconic clown face of “Tillie” onto the Palace Amusements building in Asbury Park (see photo above). He even designed and installed the neon for the face. (Not to brag, but my article was a scoop. For decades, the identity of the Tillie artist was unknown to the public.)

So, what is an in-betweener? MacMillan defined the role for me: “An in-betweener is someone who gets handed the key frame drawings, say every fourth drawing, and has to draw all the rest. The head animator draws the main motions — like, an arm at rest, then picking up a phone. They tell the in-betweener that six more drawings are needed, and how fast/slow they should go. All of which means Lorraine was actually a very good artist and an extremely talented animator. In-betweeners have to be excellent draftsmen, often better than the key animators.”

Nuts! My time with the Thomases that day was limited, but I wish I had taken at least a few minutes to interview Lorraine about her Fleischer days. Worth Thomas died at age 90 in 2003; Lorraine Thomas died at age 94 in 2011.

“Regret of neglected opportunity is the worst hell that a living soul can inhabit.” — Rafael Sabatini