Popoca returns (three times)

By Mark Voger, author

‘Britmania: The British Invasion of the Sixties in Pop Culture’

In opening narration, an authoritative voice informs us that “The Aztec Mummy” (1957) is based on a real-life experiment from “the Institute of Hypnotherapy of the University of Los Angeles.” (Google turned up the similarly named Hypnosis Motivation Institute in Los Angeles, so I suppose the story really happened, as is claimed.)

During a convention of his fellow scientists, earnest Dr. Eduardo Amada (Ramon Gay) extols the glories of regression therapy. One attending scientist, Eduardo’s buddy Pinacate (Crox Alvarado), is what we gringos call a “nerd.” (Poindexter hair and Mr. Magoo spectacles are the giveaways.) Eduardo’s lovely fiance Flor (Rosita Arenas), daughter of learned Dr. Sepulveda (Jorge Mondragon), volunteers to be placed under hypnosis for Eduardo’s next experiment.

During Flor’s regression therapy treatment, we time-travel with her to an ancient Aztecan ritual with lots of feathers, torches, dancing, percussion, and a virgin princess named Xochi who — whaddaya know? — looks a lot like Flor. “I have been consecrated to the party of Toxcatl in honor of the god Tezcatlipoka,” Flor says with eyes scrunched while in her trance. (Program note: The spellings are OK.)

Through Flor, Xochi speaks of being sacrificed in “eight moons,” a period during which she much remain a virgin. But a beefy Aztec warrior named Popoca (Angel Di Stefani) is in love with Xochi, and he doesn’t care who knows it. As punishment for his impertinence, Popoca is forced to swallow an elixir that bestows eternal life, and he is sentenced to guard Xochi’s tomb for all eternity. (Yep, the ancient Aztecs were no more lenient than the ancient Egyptians.)

In this flashback, when the high priest knifes Xochi, Flor also “dies.” Thankfully, Eduardo and his fellow observers manage to revive her. All of this occurs under the watchful eye of a hidden character: the Bat (Luis Aceves Castaneda), a masked criminal mastermind with a seemingly endless supply of henchmen.

Eduardo resolves to find the tomb of Xochi, in order to acquire the golden, jewel-encrusted breastplate and bracelet she was interred with. Flor urges against this, lest the gods put a curse on her fiance. Even their butler Jose, who is of Aztecan descent, warns against the idea. Eduardo — as any mummy movie fan knows — will regret not heeding these warnings.

The Bat, too, covets Xochi’s bling. He is convinced that ancient hieroglyphics (are there any other kind?) on the breastplate will lead him to the legendary Aztec treasure.

Flor, drawing on Xochi’s memories obtained via regression therapy, leads an expedition to the Aztec temple, where they find the pieces — not to mention the reanimated Popoca, now a withered, long-haired mummy who is mighty angry at the intrusion. Dr. Sepulveda shoos Popoca away with a crucifix. (Um, is the mummy a vampire? In a later film, he also changes into a bat.) The expedition escapes the temple with the pieces in tow, leaving behind a flailing Popoca.

But all hell breaks loose at Eduardo’s homestead, and honestly, he brought it on himself. Popoca invades the house in search of the breastplate and bracelet, while the Bat’s henchmen kidnap Eduardo’s daughter, Anita (played by an unidentified actress), and Flor. What next?

One, long slog

The three films in the trilogy — all directed by Rafael Portillo — were shot in one, long slog. And they look it. The films have the same characters and sets, and there is much redundant footage. Huge chunks of the Aztec flashbacks are seen in all three, which is fairly excruciating, and even a little bit angering, if you binge-watch the trilogy.

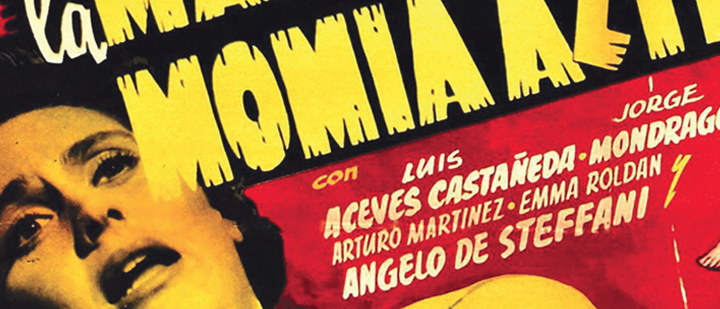

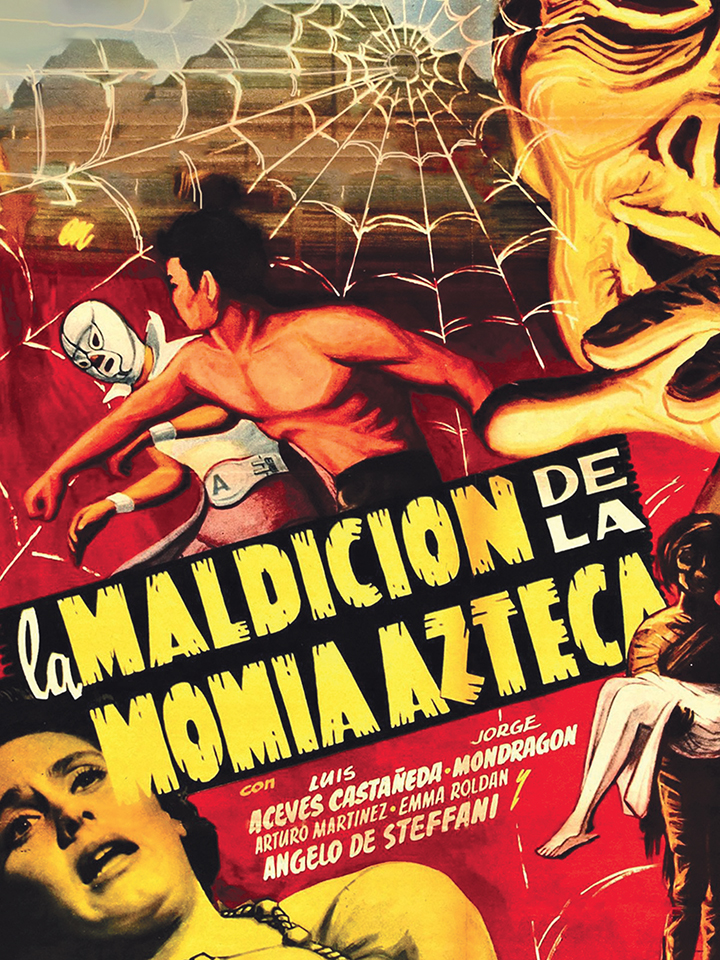

Despite the back-to-back shooting schedule, the movies in the trilogy are distinct from one another. The first film presents the origin story of the Aztec mummy. The second film, “The Curse of the Aztec Mummy” (1957), introduces the masked hero the Angel, who lends the series a luchador feel. I won’t spoil the identity of the Angel, but it’s a real shocker.

(OK, it’s Pinacate. The shock is that there’s, like, a 70-pound difference between Pinacate and the Angel.)

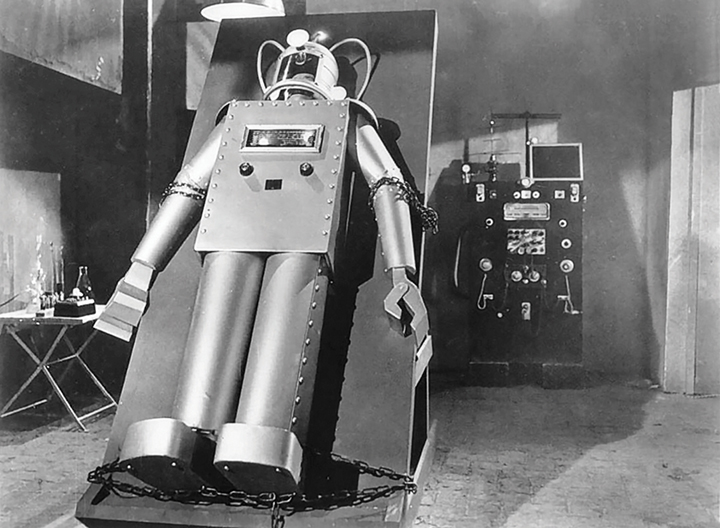

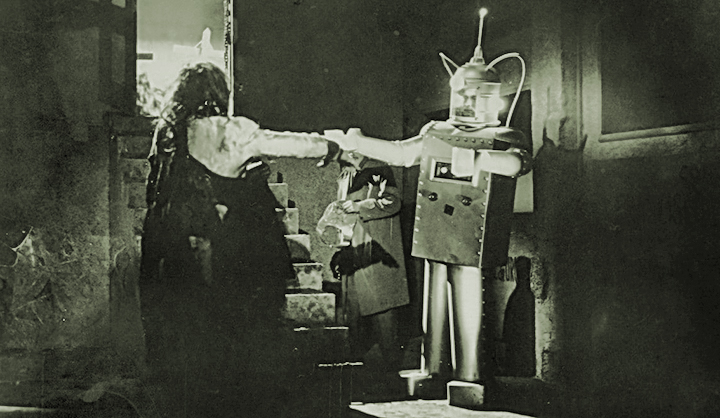

The third (and best known) film, “The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy” (1958), shows us new — no pun intended — digs for Popoca, who settles into a historic cemetery, specifically the crypt of “Francisco de Urquijo, Count of Oaxaca, Last Descendant of Aztec King.” (It says so on the entrance.) But mostly, “TRVTAM” is about the battle royale between the title titans.

OK, “titans” is hyperbole. That robot looks like a guy wearing a big cardboard box spray-painted with Rustoleum, festooned with old radio parts purchased at a garage sale. “Metropolis,” this ain’t.

But, not for nuthin’, that sensationalistic title puts “TRVTAM” in a category with “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man,” “King Kong vs. Godzilla,” “Dracula vs. Frankenstein” and “Freddy vs. Jason.” If you’re feeling generous.

Post script

There were more Aztec mummy movies, but this is “the trilogy.” The first such film to follow Portillo’s original three was Rene Cardona‘s “Las Luchadoras Contra la Momia” (1964). This sequel to Cardona’s “Doctor of Doom” (1963) presents an entertaining revisiting of Popoca’s world with fresh flashbacks (thankfully) photographed at what appears to be the same pyramid exterior. It also boasts a new character design for the Aztec Mummy, with more detail — almost approaching Mrs. Bates territory — and facial articulation.

It’s an improvement, undoubtedly, but I wouldn’t trade the original Popoca for all the coffee in Oaxaca.

MOVIES

Above is “Curse of the Aztec Mummy” in Spanish with subtitles. Monster movies are an international language, yo!

“The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy.” Time to nuke some popcorn.