Empowerment or exploitation?

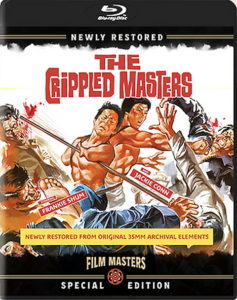

‘The Crippled Masters: Special Edition’

‘The Crippled Masters: Special Edition’

Film Masters

$24.95 (Blu-ray), $19.95 (DVD)

91 minutes plus special features

Not rated

By Mark Voger, author

‘Zowie! The TV Superhero Craze in ’60s Pop Culture

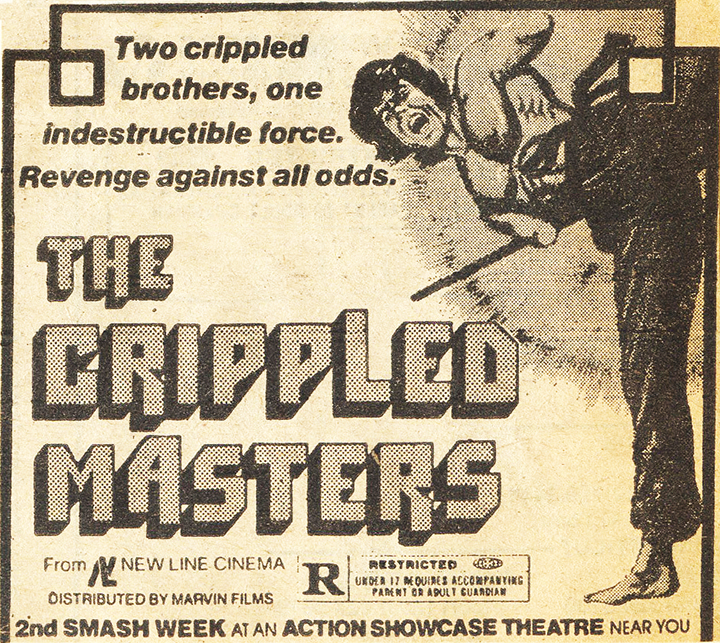

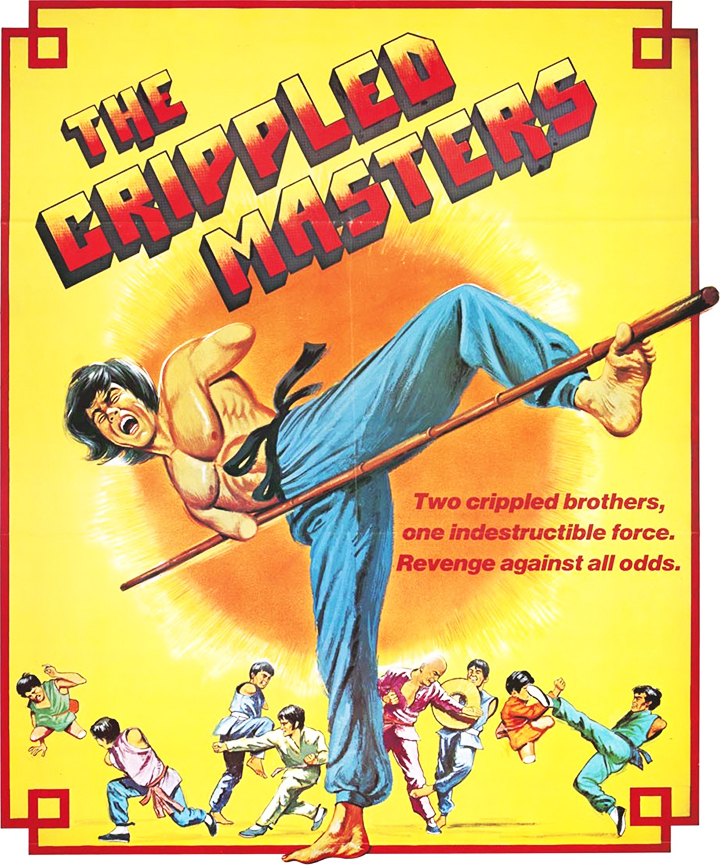

An under-the-radar cult film from 1979 not seen in America until 1982 is suddenly getting its biggest mainstream exposure. This week, Film Masters has released a restored print of the kung fu movie “The Crippled Masters” to home video.

As its problematic title might indicate, this is not your run-of-the-mill kung fu movie.

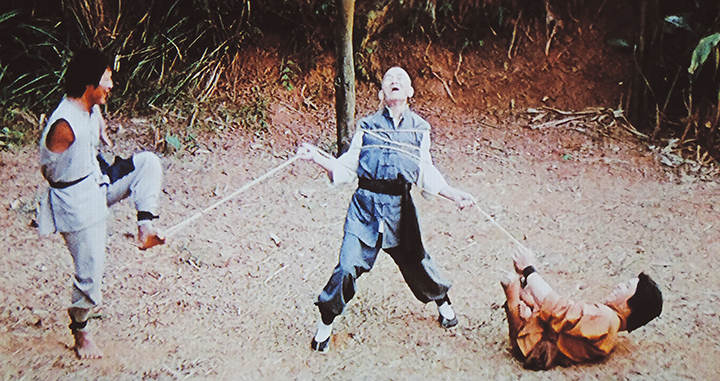

The Taiwanese film concerns two fighters — one without arms, the other without working legs — who seek revenge against the gangster responsible for their disabilities.

There’s no faking it here. The actors — Frankie Shum and Jackie Conn (their Americanized names) — lived with these disabilities. Whether you view director Joe Law‘s “The Crippled Masters” as a gawkfest or an exercise in empowerment is entirely up to you.

But if you love this genre, you may lean toward the latter categorization. Kung fu movies are all about amazing choreography and stunt work. Or, put another way, physical achievement. As you watch Shum twirl a staff with speed and precision … or Conn elude an attacker’s blows by running on his hands … or both team up to become one fighter with arms and legs … well, you can’t help but root for them.

Everybody Chang Kung

Plot: In the village of Pua Chi, the fearsome mob boss Lin Chang Kung (Li Chung-Chien) rules with an iron fist. Displeased with Lee Ho (Shum), an escort in his employ, Lin directs underboss Tang Su Ching (Conn) to have Lee’s arms cut off.

Lee survives the dismemberment, and stumbles around trying only to live. At an eatery, he is ridiculed by a waiter (Pei Di-Yun) and beaten up by a pudgy bouncer (Pang San). Left for dead, Lee ends up in the workshop of a coffin maker (Tai Liang) who encourages him to make a fresh start. Lee finds work on a farm, where he totes water, lugs timber, and operates a rice mill with his legs. He even performs feats of dexterity to entertain the local children.

Meanwhile, Lin turns his ire upon Tang, who he believes has not been sufficiently subservient. As punishment, Lin pours acid on Tang’s legs, rendering them useless. Tang is in a terrible state, rolling around the countryside in agony, when he encounters Lee — the very man whose arms he gave the order to be severed.

So the tables have turned. Lee immediately decides to take revenge by killing Tang slowly. But fate intervenes when the two men are joined by a somewhat comical elderly teacher (Ho Chiu) with seemingly superhuman flexibility. The old-timer can fold himself into just about any position. Luckily for Tang, the teacher has one question for Lee: “Why don’t you forgive him?”

He then trains Lee and Tang how to fight as a single unit, and urges them to take revenge on the true culprit: Lin Chang Kung.

Cinematic precedents

You have to admire the on-screen achievements of Shum (a survivor of thalidomide syndrome) and Conn. And lest you write off “The Crippled Masters” as mere exploitation, take note that it has some credible precedents.

In Tod Browning‘s 1932 horror film “Freaks,” real-life sideshow “oddities” — this was a different time — were cast as members of a traveling circus. In William Wyler‘s “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946), veteran-turned-actor Harold Russell won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role as a returning soldier who lost his hands during World War II, as Russell did in real life. I would argue that both of these films treated their differently enabled characters with dignity.

In a booklet accompanying Film Masters’ release is an essay written by Lawrence Carter-Long, a kung fu movie aficionado and curator who lives with cerebral palsy. Writes Carter-Long: “With the passage of time, ‘The Crippled Masters’ has survived to occupy a unique, seminal, and essential shift in the cinematic representation of disability by obliterating conformist narratives that for far too long, and far too often, relied almost entirely on antiquated tropes and yawn-inducing stereotypes.”

Film Masters is leaning in by noting that July is Disability Pride Month. We’ll soon learn the buying public’s verdict on “The Crippled Masters.”

Special features include lively commentary by Will Sloan and Justin Decloux of the Important Cinema Club; “Kings of Kung Fu,” Ballyhoo Motion Pictures’ short documentary about the introduction of kung fu movies in the United States; a collection of kung fu trailers from Something Weird; the 1982 trailer; that trailer recut with restored film elements; and the raw scan of “The Crippled Masters” — a scratchy English dub with French and Dutch subtitles that helps you appreciate the quality of the restoration.