I was a guest on “Castle Talk,” BleedingCool.com’s “Castle of Horror” podcast hosted by Jason Henderson, author of HarperCollins’ Alex Van Helsing novel series. Jason and I spoke about how “Leave It To Beaver” reflected monster culture; how Batman fought monsters on trading cards; and the “alternate universe” presented in Dan Ross’— or was that Marilyn Ross’— series of “Dark Shadows” novels. Jason podcasts from Denver; he posted our conversation on April 18, 2017.

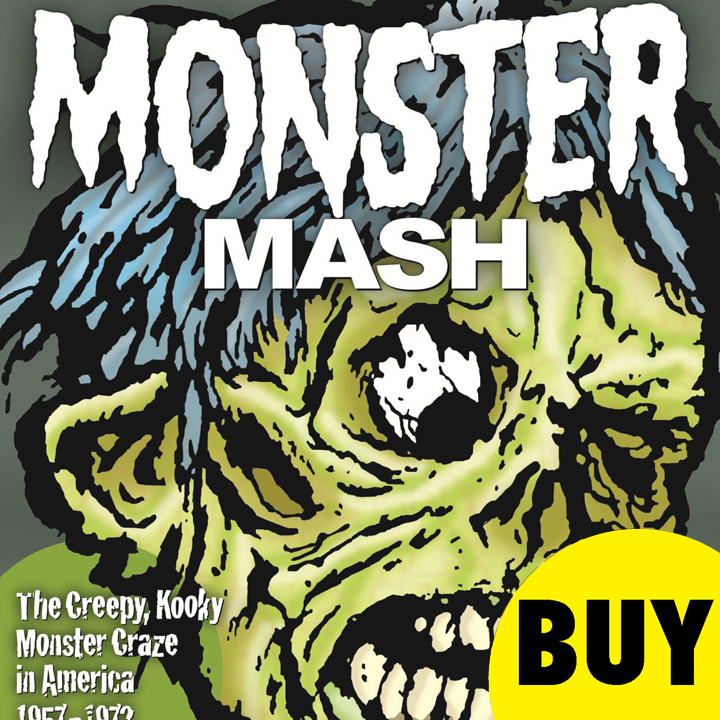

JASON: I’ve been looking at this book for a while. It’s just so fun. It’s kind of a grown-up version of Famous Monsters of Filmland. It is a hardback tour of monster culture. Why is it called “Monster Mash”?

JASON: I’ve been looking at this book for a while. It’s just so fun. It’s kind of a grown-up version of Famous Monsters of Filmland. It is a hardback tour of monster culture. Why is it called “Monster Mash”?

MARK: Well, of course, I’m trying to evoke the song title, by Bobby (Boris) Pickett. Because the whole thing was — in the ’60s, they were making this stuff kid-friendly, they were making it palatable to children. So it really was creepy and kooky. It was very scary, but there was something funny about it, too — the monster models and the comic books and the comedy TV shows and even that song.

JASON: Interesting. You say, on the cover, that you’re covering the Monster Craze that began in 1957 and ends in 1972. You’re saying that part of it involves a kind of innocence, I guess. Why ’57 to ’72? What’s going on there?

MARK: That’s a good question, Jason. It’s always easy to pick when a trend like this begins. Everybody can agree. Showcase #4 in ’56, with the new Flash, kicked off the Silver Age (of comics). People can agree on the “big bang.” It’s when it ends that is trickier to pinpoint, because there’s not a big bang for its ending. So some people have disagreed with my call to end it in ’72. But I have my reasons. One thing is that it’s a clean 15-year period. But also, “The Exorcist” came out in ’73. I don’t want to get too vulgar, but you know what she does with a crucifix — things that Van Helsing never would have done. That’s where the innocence was lost. “Dark Shadows” was cancelled in ’71. All these little things started happening. Famous Monsters started to really slide; they kept publishing through ’83, but they started to rely more and more on reprinted material, and they weren’t quite keeping up with the times. So I think that the golden era was over by ’72. But, of course, like any good trend, it kept going. Beatlemania kept going.

JASON: I think I see where you’re coming from. Because there’s always going to be people you can run into at a car show who will go, “Oh, no, because so-and-so is still keeping the Famous Monsters flame alive!” Or Basil Gogos — it’s not like you can’t actually call him up and get him to come out to a show. But that’s not the same thing as a living trend. This was where the culture was — where if you were a regular kid, you were going to be embracing the monster world. And then there was a point after which, no, you’d have to be kind of what we now call a geek to be into this stuff. A hobbyist. But the culture had moved away. The thing that proves to me the most that the culture was there: You talk about an episode of “Leave it to Beaver.” “Leave it to Beaver,” for the listeners who don’t know — and that’s completely plausible — was an enormously successful and important sitcom about a pair of brothers who are growing up in small-town America, suburban America, I guess you’d say. How did “Beaver” cross over into the monster universe?

MARK: Well, in particular, I wrote about an episode in which Beaver (Jerry Mathers) and all his friends buy monster sweatshirts at a store in downtown Mayfield, where they were growing up. And the name of the episode is “Monster Sweatshirts.” They make a pact to wear them to school, and of course, only Beaver goes through with it. He gets in all kinds of trouble. But the episode itself is filled with all these arcane references to how monster characters were looked down upon. Everybody’s looking askance at them. Because in those days, parents and educators and clergy and politicians all looked down on monster characters. And then in other episodes, too, they (Beaver and his friends) are always staying up to watch monster movies, or going to a terrible monster movie in town. It was at the height of that period, so there were a lot of references throughout the five seasons.

JASON: That’s what I was thinking of with the monster sweatshirts, where he’s wearing kind of a Rat Fink shirt, which is ugly to look at, but it’s nothing, really. It’s just a three-eyed monster. It’s just sort of tasteless — tasteless in kind of an eighth-grader-in-the-’50s kind of way. So, yeah, he gets sent to the principal’s office. But that’s where the culture was. Boys started to get into monsters.

The way you’ve got this book divided up, and it’s amazing to me, you have these sections as you go through — sometimes as little as three pages, sometimes 20 or so pages — where you’re going over different topics. So you spent time, for instance, looking at the model kits from Aurora. They made models that were sold all over the country. And you interviewed the artist who made the paintings for those (model boxes).

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST HERE OR CLICK ON THE VIDEO BELOW.

MARK: Yeah, the great James Bama, who is still living. He’s more famous now for doing paintings that depict the Old West. He does these great American Indians; he does every wrinkle on their faces, every little feather. But he said something funny. He said that the world could come to an end, but people will still remember his Aurora monster model covers. He can’t believe we remember that stuff. But they are so beautiful. So it’s no surprise he turned into a contemporary of Norman Rockwell in later life.

JASON: They are a distinctly American kind of art. Amazing paintings. He uses color in such a daring way, so that there are all these vivid greens and reds. So his painting of the Phantom of the Opera is awash in all of this color. What I love that you bring to this book is your own very esoteric knowledge. So you could recognize that the model that he uses for his painting of the Phantom of the Opera is not Lon Chaney, but Jimmy Cagney. I thought that was hilarious.

MARK: Yeah. He used whatever he thought was appropriate. He wasn’t bound by any sort of: “I should make it Lon Chaney Sr.” He just used whatever image he responded to. On the subject of the colors, Jason, he did say that they were intentionally garish. They weren’t painted to hang in a museum, although they certainly should. He said they were painted just for reproduction. He did a lot of paperback covers. It was the same thing with Basil Gogos. They used the color palette that they knew would sell on the newsstand.

JASON: It really does pop. It takes so much imagination for somebody like Basil, for instance, to look at a black-and-white image of Lon Chaney in “London After Midnight,” and sort of imagine where all the yellows and reds and greens will be in that image. Gogos is fascinating. We got a chance to see him at the Colorado Horror Con just last year.

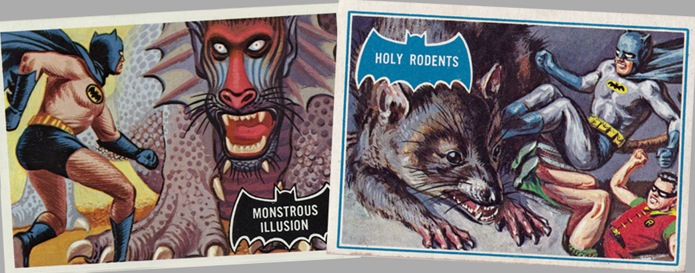

You found something else that I was amazed at. I’d never seen this before. Going through this book was an exercise in, every other page, going, “Oh, wow, I know that. I recognize that. I’ve heard of that.” So you’re re-reading the same stuff — which is exactly the experience of Famous Monsters of Filmland — and sometimes coming across stuff I had no idea about. Like, these weird Batman monster cards. What is up with those? Did you actually find these cards?

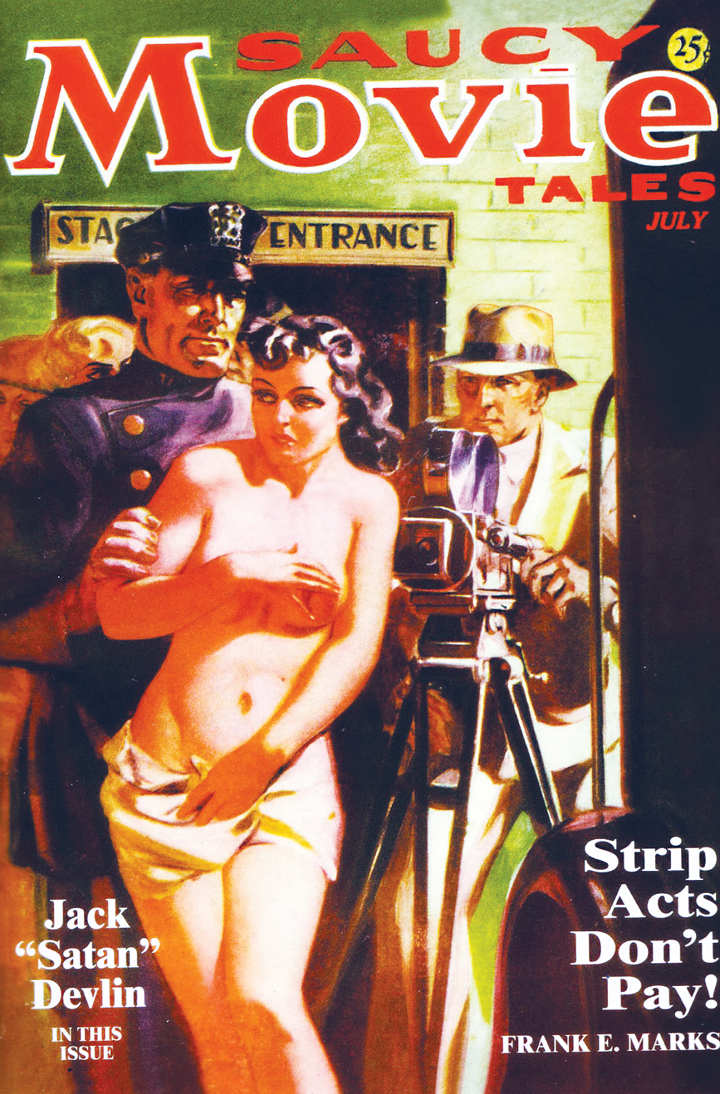

MARK: Jason, I still actually have my collection from 1966. When I was 8 years old, I collected them all. And the reason those are so beautiful is they were done by Bob Powell, who did the pencils sometimes — he was a great comic book artist — and Norman Saunders, who is one of the great pulp artists. He did pulp fiction covers going back to the ‘30s. He did the finishes. They were little paintings. He always used to do girls in ripped blouses stuck in a spider web being pursued by a giant spider. He would do that for the pulp covers. So he was bringing that back. It wasn’t in the Batman TV show. It wasn’t in the Batman comic books. They were bringing the pulp style to Batman. I think that was the reason. Monsters were still hot in ’66. But these guys came from that pulp tradition.

JASON: It’s really amazing. Like this one where Batman is being attacked physically by a giant bipedal catfish. There’s one where he’s tied up by the Joker, and the Joker really looks a lot like the Phantom of the Opera. It’s so cool to see an artist who clearly doesn’t have any personal investment in the subject matter, but has a lot of art style of his own, and has a great desire to bring his own spin on it. It’s amazing. I’m just curious — did you take pictures of your own cards? How did you do these reproductions?

MARK: Well, I’m also a graphic artist. I’ve worked in newspapers all my life. I turned pro in ’78 when I was 19 years old. And I’ve always written and designed. So I’ve acquired all the tricks. So, for instance, for the Batman cards, I scanned those from my original collection. I’m also very proficient in Photoshop, so I can perfect an image. Or, even better, I can leave the nasty stuff in. So if you look through “Monster Mash,” you’ll see that there’s a lot of, like, scratches or tears. Because I’m really trying to make the reader feel like they’re looking at almost a mummified edition of the original. But if there’s a scratch in an awkward place — if there’s a scratch over a face or something — I would take that out. But for the most part, I really tried to let the nastiness breath.

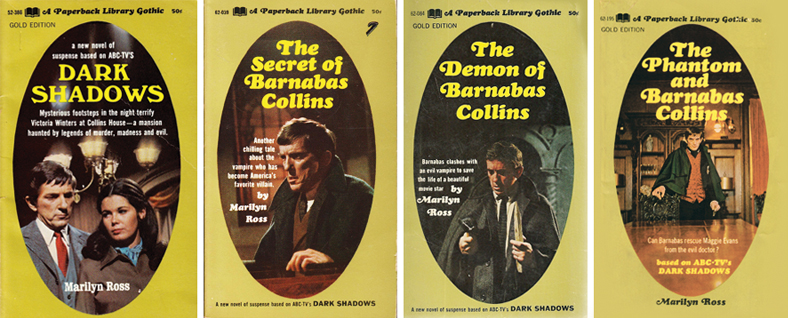

JASON: You have a section on Dan Ross’ “Dark Shadows” books — basically, Gothic romances set in the “Dark Shadows” universe. I love those books. I collect them. I have the absolutely terrible “Barnabas Collins in a Funny Vein,” which was not written by Dan Ross, as you point out. Those are really cool. You must have a heck of a collection of these things.

MARK: I do have the entire set of the “Dark Shadows” novels. They’re fun because — quote, unquote — “Marilyn Ross” decided not to just do novelizations of episodes. He just went in his own direction. He created almost an alternate universe of the Collins family.

JASON: It really is. It’s absolutely an alternate universe. It’s an utterly different “Dark Shadows” that has a lot of the same characters, but other characters who also don’t exist (on the TV show), and the house is called something different (Collins House). He was writing so fast that he didn’t have time to keep track of what, exactly, was going on on the show. So by the time he was several books in, he had completely diverged from the continuity of the show. It’s pretty amazing. It’s cool stuff.

OK, I have one more thing to ask you about, and that’s “Shock Theater.” What was “Shock Theater,” and why is it still remembered?

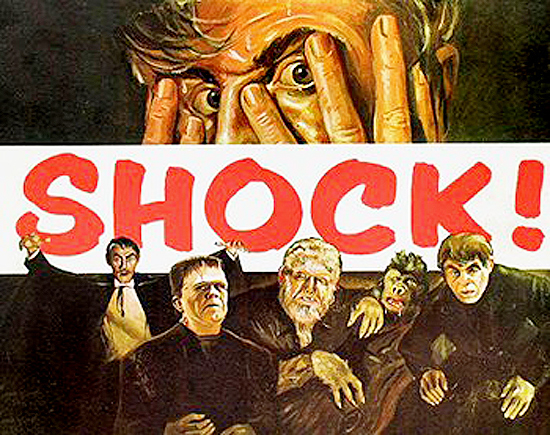

MARK: Well, Jason, earlier we were talking about the “big bang” that started this. There’s absolute consensus on that, that it happened in ’57. What happened was, Screen Gems made a package. These movies had never been on television before. And obviously, in 1957, television hadn’t really been around that long, as commercial television. But Screen Gems put together a package of 52 horror and horror-ish movies, and made them available to television. But they didn’t — and this is telling — they didn’t offer them to the networks. The networks wanted nothing to do with them, because they had these deep-pocket advertisers. They didn’t want parents complaining to the sponsors that, “These movies gave my children nightmares.” So (Screen Gems) offered them to the local little independent stations in every city. They (the stations) grabbed it, because they were just hungry for content. They didn’t have big budgets for programming. And in one case, one station reported — I believe it was a 1,125 percent increase in the ratings in the same time slot from a week earlier. So this really hit a nerve immediately. Immediately, people took notice that the ratings were so powerful.

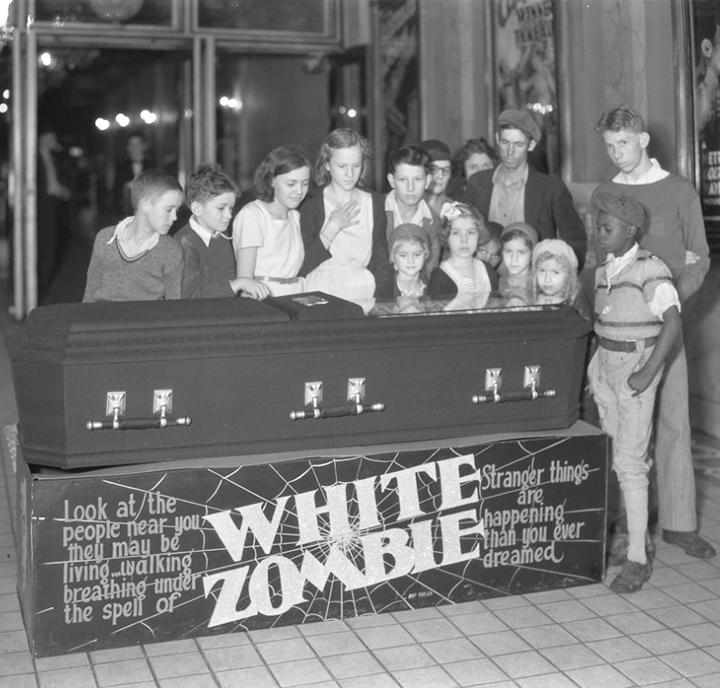

JASON: So it was horror material, and they came up with this inspired technique for presenting it — to give a fresh coat, basically, to this horror material. Which is what people remember the most, really, because the movies — some of them were good, some of them were not so good. I’m just wondering: How did they come up with this notion? Basically (in a commanding voice), “You in Duluth, you in Dallas, you in Santa Monica, you’re going to find somebody, and you’re going to fill in these doughnuts, these bumpers, right before the commercials.” I wish we could get to the guy who was sitting around, bouncing his baseball against the backstop at the office at some studio somewhere, and said, “I’ve got it! We’re going to send these out around the country, and let people create bumpers to go around ‘The Fly,’” or whatever.

MARK: Well, there was a tradition that it sort of dovetailed off of. It was called “ballyhoo.” A lot of times, when they were trying to promote movies — theatrical films that would be in movie theaters — the movie studios would send press kits, advertising “slicks” and publicity materials to the theaters. But it would be suggested — for instance, if it was an Esther Williams film — they might say, “Have a girl in a bathing suit out front waving to everybody.” I made up that example, but they would do things like that, suggest things like that. So Screen Gems suggesting that you have your own horror host to introduce it was just another form of the ballyhoo that had begun in the movie era. It was great, Jason, because it made (watching monster movies) feel like an event. And monster nerds are lonely people. So it made us feel like we had a friend.

JASON: I grew up with one. Channel 11 in Dallas-Fort Worth. There was the guy — it was Cecil Creape, I believe. Is that right? You know what? Someone’s going to write in and say, “No, you moron, that wasn’t Cecil Creape.” But it was the guy who hosted “Slam Bang Theatre” — the same guy who hosted the cartoon show and the monster show when I was growing up. (Laughs) And that’s probably true in a lot of suburbs. Anyway, you have this long section. You have an interview with Zacherley (John Zacherle). You have all of this Zacherley material. I mean, this is really a labor of love. I really want people to take a look at this thing and see this book, because I just never get tired of picking it up and flipping through it.

VIDEO: Watch the “Monster Mash” trailer below.

MARK: Jason, from your lips to God’s ears.

JASON: (Laughs) Well, Mark, gosh. It’s been so great talking to you. The book is called “Monster Mash: The Creepy, Kooky Monster Craze in America 1957-1972” by Mark Voger, and it’s from TwoMorrows Publishing. “Monster Mash” — you absolutely have to check this thing out. Thank you so much. I really appreciate you coming on.

MARK: Thank you, Jason. I had a blast. And good luck with your next project, sir.

JASON: Oh, yeah. You know what? I might ask you about everything it takes to gather up content for a non-fiction book. Because I have to turn in a book about tiki culture by the end of the summer (laughs). So you and I will discuss that.

After we went off the air, I gave Jason the best advice I could think of regarding his forthcoming book on tiki culture: Hollow out a pineapple, and fill it with booze.