Following are excerpts from a section on psychedelic art in

“Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture” (TwoMorrows Publishing)

Waiting to take you away

Psychedelia was a genre exclusively bound to no format. It was music. It was fashion. It was movies. It was photography. It was dance.

And it was, um, recreational imbibing.

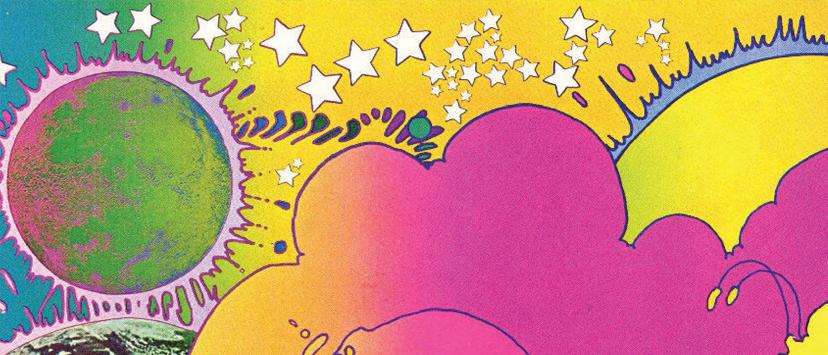

But there was one medium that seemed to inform all others, one that set the crazy-colored, anything-goes tone for the genre. And that was … art.

The wildest of psychedelic music seemed bent on evoking the visual. In that imbibing department, there was much talk of “tasting colors.” Fashions, album covers, typography and set design in film all borrowed liberally from visual themes in psychedelic art. Art was — as the hippies used to say — where it’s at.

Where did psychedelic art begin? Cave paintings from as far back as 38,000 B.C. may have been inspired by hallucinogens. The kaleidoscope — an enchanting invention which likely provided the earliest examples of what can confidently be called psychedelic art — was invented in 1816 by Sir David Brewster, a Scottish scientist.

The Modernism art movement, which defied centuries-old art conventions with experimental, free-form approaches — originated in the late 19th century. Modernism paved the way for other groundbreaking movements, such as Dadaism, abstract expressionism, surrealism, cubism, pop art and op art.

Among the best-remembered boundary-pushing artists of post-Modernism are Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Salvador Dali (1904-89), Pablo Picasso (1908-73), Jackson Pollock (1912-56), Roy Lichtenstein (1923-97) and Andy Warhol (1928-87).

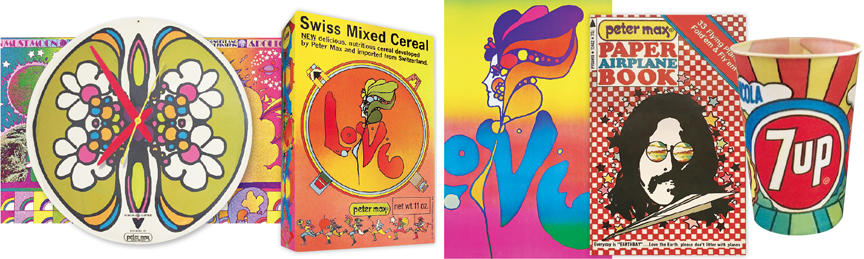

Psychedelia as we know it was commercialized for a mass market once pop and rock musicians began experimenting with hallucinogens — hence their music, hence their album covers, hence their clothes and lifestyles. Rock became the vehicle of delivery globally and locally.

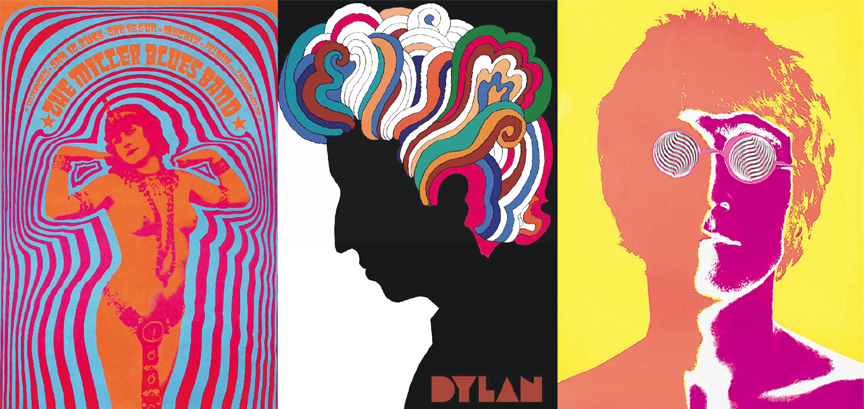

Posters that advertised rock concerts in San Francisco (especially), Los Angeles, New York and other cities proliferated from the mid to the late ’60s, and took psychedelic art into even crazier climes. The often distorted lettering on the posters — you almost had to be high to read it — handily weeded out mismatched potential patrons of such events. If you can’t read the poster, mannn, this show isn’t for you.

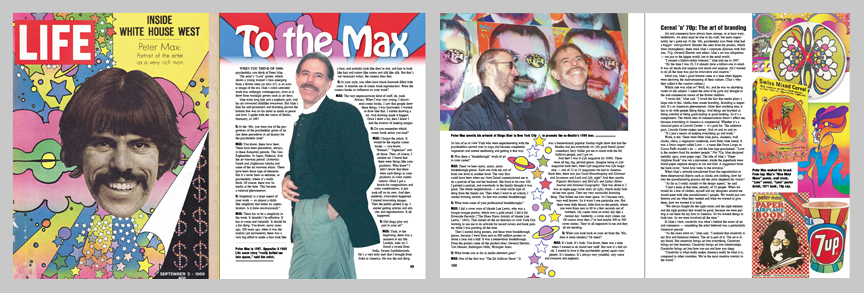

Peter Max on precedents to psychedelia in art history: “There have been precedents, always, in these Romantic periods. The Neo-Raphaelites. In Japan, Hokusai. And the art nouveau period: (Antonio) Gaudi and (Alphonse) Mucha and some of the art nouveau artists. There have been those type of elements. But it’s never been so extreme, so psychedelic, where it’s really fresh. Of course, there was no media at the time. This became a national phenomenon.”

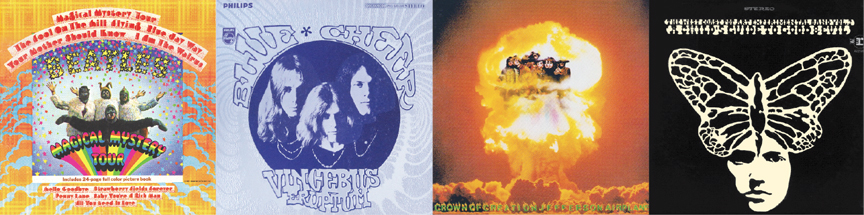

Graphic artist John Van Hamersveld on designing the “Magical Mystery Tour” U.S. album cover: “What happened was this: (the Beatles’ manager) Brian Epstein died. Between the (Capitol Records) vice president and myself, his problem was that the record was not a hit there. The TV movie registered as ‘unliked.’ He was in a bind, because normally (British record company) EMI provided the artwork for the covers. He said, ‘Try to make this psychedelic, and get back to me.’ I went back to my studio. I had been working on posters for (the promoter) Pinnacle Rock Concerts. So I had graphic information that I brought into the cover — the dots and the typography and the curvatures and the negative-and-positive figures.”

SEE: ‘Groovy’ preview HERE

ORDER: ‘Groovy’ at TwoMorrows, Amazon, Target, Walmart

READ: More ‘Groovy’ excerpts HERE