It only took 56 years

By Mark Voger, author

“Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture”

Spoilers follow.

I bought the novel “Dracula” in 1965, when I was in the second grade. I had every intention of reading it, really I did. But the language was a bit too old-timey for a 6-year-old. And nothing monster-y was happening. It was just some guy talking endlessly about his trip to visit Dracula. I lost interest pretty quickly, and never got past the first chapter.

I’m now 63, and earlier this week — ta da! — I finally finished reading “Dracula.”

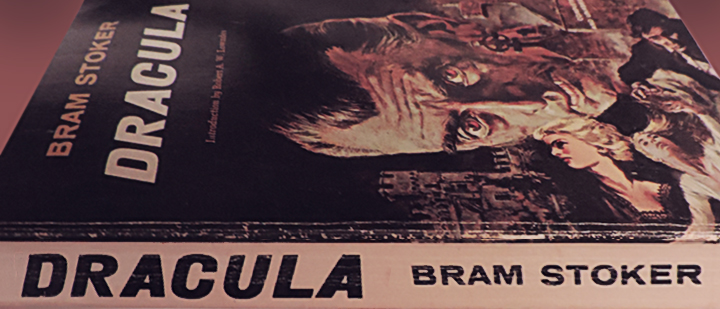

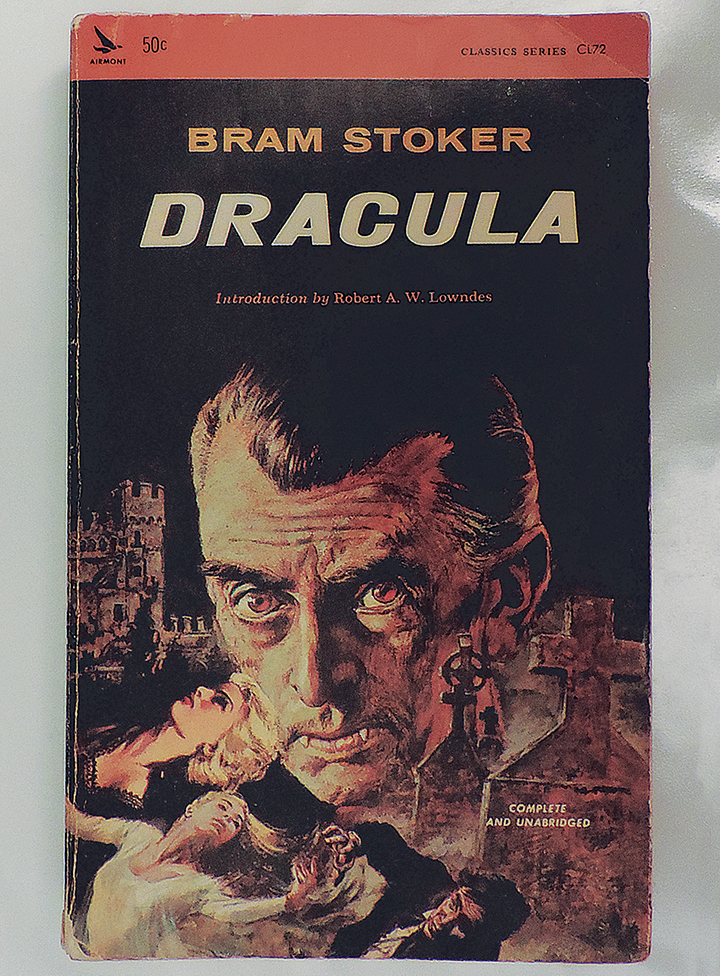

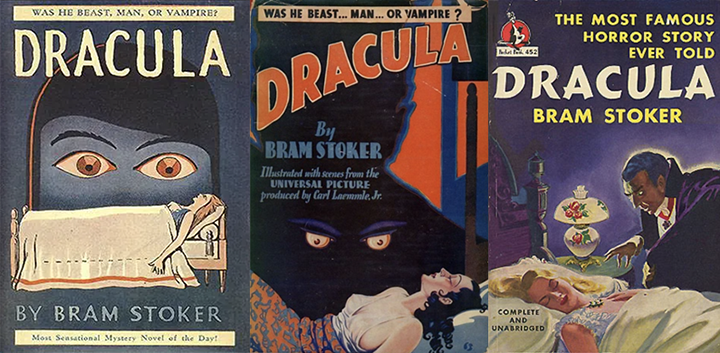

It only took 56 years for me to try again, and then three months to read it. (It became my “traveling” novel for out-of-town trips.) The fact that I was reading a copy of the 1965 paperback edition issued by Airmont Publishing of New York City — the same edition I owned when I was 6 — was meaningful for me. (I found a copy on the eBay. It cost 10 bucks, as compared to the 50 cents I paid in ’65.)

I loved it. I was entranced by it. At times, I was actually unnerved by it. The book lived in my mind from night to night. It dawned on me what a pioneering work Bram Stoker, a native of Dublin, created. I began seeing Stoker’s influence everywhere. The bat scratching against the window in a “Dark Shadows” episode … the imagery on a box of Count Chocula … it all began with Stoker’s novel.

I’m not saying “Dracula” is a flawless work. The middle kind of dragged, as the Count kept draining Miss Lucy of her blood, and Prof. Abraham Van Helsing kept filling her up again with blood from various donors. It dragged again near the end of the book, when our six heroes — Van Helsing, Jonathan and Mina Harker, Lord Godalming, asylum head Dr. Seward and visiting Texan Quincey Morris — kept strategizing and pumping each other up to find and kill Dracula. It went on and on. I kept thinking: “Ten pages have gone by, and they’re still talking about how they’re gonna find and kill Dracula?”

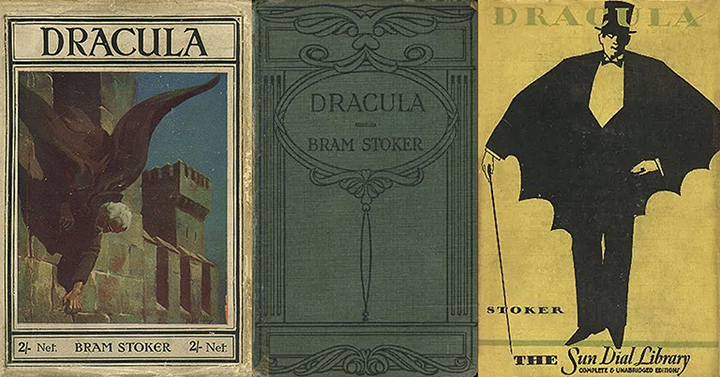

Those are my only two complaints, and they can certainly be ascribed to the huge gap in years between the time Stoker’s novel was published, in 1897, and the time I read it, in 2021. A century and a quarter later, “Dracula” is still a vibrant novel with a modern voice. Or voices.

Stoker is a master of dialect. The book is written in what novelist Wallace Stroby informed me is called an “epistolary” approach. (Don’cha love learning new terms?) “Dracula” is not a narrative told from single point of view such as first person or omniscient narrator (aka third person). It is told in a more or less chronological series of dated letters; diary entries; memorandums; telegrams; invoices; newspaper articles; and other written forms. Thus, Stoker is channeling many voices. My ears loved the queer way of talking that the author employs when “quoting” old salts and working stiffs in remote locales.

Have a listen to Mr. Swales, an elderly sailor met by Miss Mina: “It be all fool-talk … that’s what it be and nowt else. These bans an’ wafts an’ boh-ghosts an’ bar-guests an’ bogles an’ all anent them is only fit to set bairns an’ dizzy women a’belderin’.”

Now to Thomas Bilder, a zoologist interviewed by a reporter for the Pall Mall Gazette: “Here’s you a-comin’ and arskin’ of me questions … and I that grump-like that only for your bloomin’ ’arf-quid I’d ’a’ seen you blowed fust ’fore I’d answer.”

Here’s workman Joseph Smollet, passing valuable information to Harker: “I heard a man by the name of Bloxam say four nights ago in the ’Are an’ ’Ounds, in Pincher’s Alley, as ’ow he an’ his mate ’ad ’ad a rare dusty job in a old ’ouse at Purfleet. There ain’t a many such jobs as this ’ere, an’ I’m thinkin’ that maybe Sam Bloxam could tell ye summut.”

Reading letters between Mina and Lucy feels like eavesdropping on two hip young women, relatively speaking, who confide in one another about their romantic conquests. (Mina is engaged; Lucy is still playing the field.)

Stoker is also a master of suggestion. I love how it slowly dawns on Harker (and us) that he has become Dracula’s prisoner, even as both men keep up the pretense that everything is perfectly normal.

There’s the report in The Dailygraph newspaper of the Demeter — a Russian schooner with a corpse tied to its wheel and no living crew — mooring itself in Whitby following a wicked storm, and of a dog bolting from the Demeter and vanishing into Whitby. (Dracula in wolf form?) In the ship’s log, the captain wrote of growing superstition among crew members who encountered a “tall, thin man” (Dracula?), and who disappeared one by one.

There were the incremental changes in Miss Lucy’s behavior and appearance — first her gums became more prominent, then there seemed to be an ever so slight sharpening of her teeth — reported by Van Helsing and others. It all preys on your psyche.

As I read, I kept revisiting the vampire movies I’ve watched all my life. When Harker witnessed Dracula crawling down the side of his castle like a spider, I could see Christopher Lee climbing up the castle in “Scars of Dracula.”

When Dracula employed aliases — even posing as Harker while wearing his clothes — it reminded me of all the aliases used by movie Draculas, such as Lon Chaney Jr. in “Son of Dracula” (Count Allucard); John Carradine in “House of Frankenstein” and “House of Dracula” (Baron Latos); and Francis Lederer in “Curse of Dracula” (Czech artist Bellac).

When Van Helsing and Seward behead Miss Lucy, I can see Peter Cushing lopping off Ingrid Pitt‘s head in “The Vampire Lovers.” (Stuffing her mouth with garlic is a nice touch … like a Thanksgiving tip.) When Harker encounters three female vampires during his castle incarceration, I see Dracula’s trio of brides from the 1931 film starring Bela Lugosi.

1897 vs. 1931

Speaking of the 1931 film, it’s a fun game to spot the ways in which “Dracula,” the novel, and “Dracula,” Tod Browning’s 1931 film, differ. (We play this game, of course, knowing that with any movie adaptation, there’s likely to be simplification, deletion and composite characters. Keep in mind also that the ’31 “Dracula,” scripted by Garrett Ford, drew from the stage adaptation written by Hamilton Deane and later revised by John L. Balderston, as well as F.W. Murnau‘s 1922 silent “Nosferatu.”) Here goes:

#1. The traveling real-estate lawyer Harker and the spider-gobbling asylum inmate Renfield in the Stoker are handily combined into one character played by the horror film’s premier lunatic, Dwight Frye (though David Manners portrays a rather conventional hero named “John” Harker).

#2. There’s more Van Helsing in the book than in the movie, and he’s (somewhat) cuddlier in Stoker’s telling. (Somehow, I can’t picture Edward Van Sloan saying things like, “Friend John, I pity your bleeding heart; and I love you the more because it does so bleed.”)

#3. Dracula’s new home in England is called Carfax in the Stoker, and Carfax Abbey in the movie (a slight, though telling, liberty).

#4. Dracula’s infiltration of London society in the movie — his attending the opera, for instance — is nowhere to be found in Stoker.

#5. In the book, Dracula is killed with two big knives wielded by Harker and Morris on a trail in the snowy Carpathians; in the movie, the deed is done with a wooden stake wielded by Van Helsing in the catacombs of Carfax Abbey.

#6-8. There are three aspects from the novel that I don’t recall seeing in any Dracula movie, let alone the Lugosi film: the telepathic monitoring of Dracula’s movements via the nightly hypnotizing of Miss Mina; the violent standoff with the Szgany (Romani workmen) hired to transport Dracula’s coffin back to his castle as dusk neared; and the problem of Count Dracula’s putrid breath. (I’m grateful the halitosis thing never made it into the Lugosi film. That was a rough passage to get through.)

Harbinger of Hammer

And here’s something that really knocked me for a loop. Five vampires are killed in the Stoker. The Count’s death — which is described in a mere three sentences — is almost anticlimactic following all of that buildup. But the killing of Miss Lucy is so gruesome, so graphically described, that it comes off more like ’70s colour Hammer than ’30s black-and-white Universal. Don’t take my word for it:

“The thing in the coffin writhed, and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions. The sharp white teeth champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam.”

Speaking of gruesome, Dracula friggin’ throws a sack containing a live baby to the three vampire ladies, as if it was takeout he picked up on the way home from work! That sh*t is harsh, yo!

Anyways, most of the above is stuff people have known for 100 years. But it was all news to me.

So I carried “Dracula” around for three months. When I was within the final 20-odd pages, I also carried my 1963 Airmont edition of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel “Frankenstein.” As planned, I read the first sentence of “Frankenstein” the moment after reading the final sentence of “Dracula.” So, in another three months or so, I’ll give you my report on “Frankenstein,” God willing.