Following are excerpts from “Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships Nov. 4).

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.

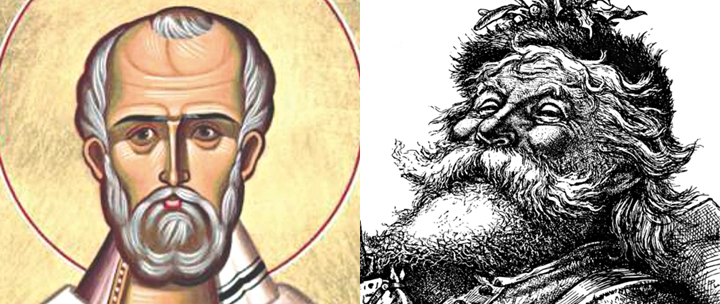

Before Nicholas became Sinterklaas

The patron saint of sailors, pawnbrokers, brewers, and repentant thieves. Sounds like a saint who didn’t mind getting his hands dirty.

But St. Nicholas was also the patron saint of children. And one constant in Nicholas’ life view is shared by the “Santa Claus” we often call “Old St. Nick”: giving gifts anonymously.

Santa makes his Christmas Eve deliveries under cloak of darkness, when children are asleep. He doesn’t hang around until morning to bask in their gratitude. The act itself is reward enough.

(This idea shows up in Dickens also. When the redeemed Scrooge sends a prize turkey to the Cratchits on Christmas morning, he delights in the fact that they won’t know the benefactor.)

St. Nicholas — born in 270 A.D., died in 342, as far as is known — was a Christian monk who lived in what is now Turkey, and at age 30 became the bishop of Myra. It is believed his parents were well-off do-gooders who died while administering to diseased people, having contracted disease themselves. Nicholas used his inheritance to fund his anonymous — and nocturnal (just like Santa) — gift-giving. One story has him tossing three bags of gold, on consecutive nights, into the home of a destitute man who was on the verge of selling his daughters into prostitution.

But wild legends were assigned to Nicholas also. One sounds like it could have been written by Stephen King (proposed title: “The Pickled Children”). In it, Nicholas resurrects three children who were murdered by a butcher and pickled in brine to be sold as — gross-out warning — pork.

Another legend in this vein has Nicholas chopping down a tree possessed by a demon. (Suddenly, the 1959 Mexican film “Santa Claus,” in which Santa matches wits with a devil, doesn’t seem so weird.)

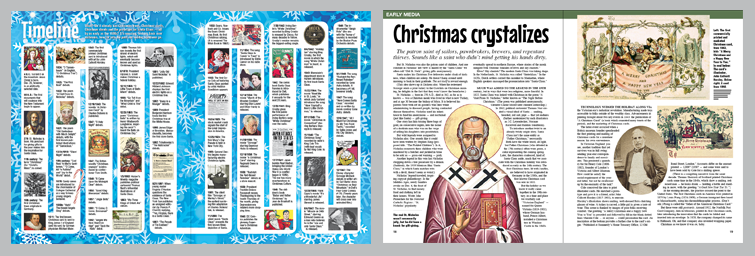

It was in the cards

Technology nudged the holiday along via the Victorian era’s industrial revolution. Manufacturing made toys accessible to folks outside of the wealthy class. Advancements in printing brought about two key events in 1843: the publication of “A Christmas Carol” (a book which cemented many tenets of the period), and the marketing of Christmas cards.

The latter event occurred when a British museum founder spearheaded the first printing and mailing of Christmas cards for a mundane reason: his own convenience. In Victorian England, you see, another tradition that yet survives was in full swing: sending year-end correspondence to family and associates. This presented a quandary for Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882), founder of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. How could he satisfy the social requirement of the year-end letter, but not be swallowed up by the enormity of the task?

Cole conceived the idea to print illustrated cards. He sketched a prototype and gave it to a friend, artist John Callcott Horsley (1817-1903), to execute. Horsley’s illustration shows smiling, well-dressed Brits clutching glasses of wine. A turkey is carved, a little girl is given a taste of wine. This scene is flanked by images of poor folks receiving comfort. The greeting “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You” is preceded and followed by fill-in-the-blank dotted lines wherein Cole — or anyone — could personalize the card. An inscription at the bottom provides a further clue to the card’s origin: “Published at Summerly’s Home Treasury Office, 12 Old Bond Street, London.” Accounts differ on the amount printed — 1,000? 2,050? — and some were said to have been sold by Cole for a shilling apiece.

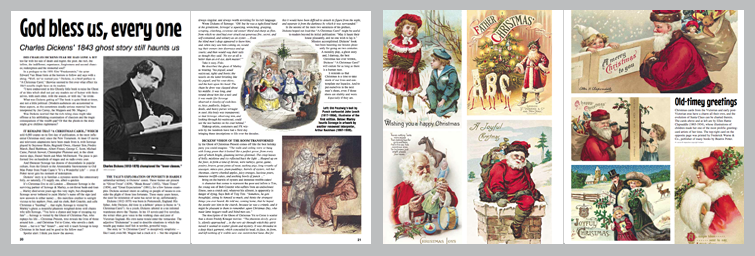

God bless us, every one

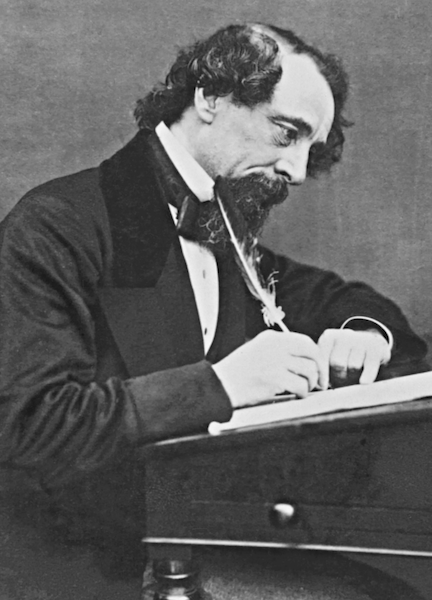

Did Charles Dickens fear he had gone a bit too far with his tale of death and regret; the poor, the rich, the infirm, the indifferent; repentance, forgiveness and second chances; redemption and the immortal soul?

In a prologue to the 1931 film “Frankenstein,” the actor Edward Van Sloan hints at the horrors to follow and says with a shrug, “Well, we’ve warned you.” Dickens, in a brief preface to “A Christmas Carol,” likewise seemed to fret over what effect his 1843 novella might have on its readers.

“I have endeavored in this Ghostly little book to raise the Ghost of an Idea which shall not put any readers out of humor with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me,” he wrote.

What was Dickens getting at? The book is quite bleak at times, and not a little political. (Modern audiences are accustomed to these aspects, as this sometimes deadly serious material has been interpreted by Jim Carrey, the Muppets and Mr. Magoo.)

Was Dickens worried that the rich ruling class might take offense at his unblinking examination of classism and the tragic consequences of the wealth gap? Or that the ghosts in the story might give children nightmares?

It remains that “A Christmas Carol,” which sold 6,000 copies on its first day of publication, is the most influential Christmas story since the New Testament. At least 15 movie and television adaptations have been made from it, with Scrooge played by Seymour Hicks, Reginald Owen, Alastair Sim, Fredric March, Basil Rathbone, Albert Finney, George C. Scott, Michael Caine, Patrick Stewart, Christopher Plummer and, in the silent movie days, Daniel Smith and Marc McDermott. The piece is performed live on hundreds of stages and on radio every year.

And Ebenezer Scrooge has dozens of descendants in popular culture, from the Grinch to the Abominable Snowmonster to Old Man Potter from Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” — even if Potter never gets his moment of redemption.

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.