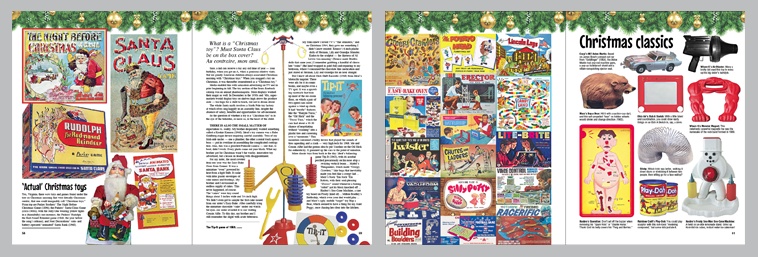

Following are excerpts from “Holly Jolly: Celebrating Christmas Past in Pop Culture” by Mark Voger ($43.95, TwoMorrows Publishing, ships Nov. 4).

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.

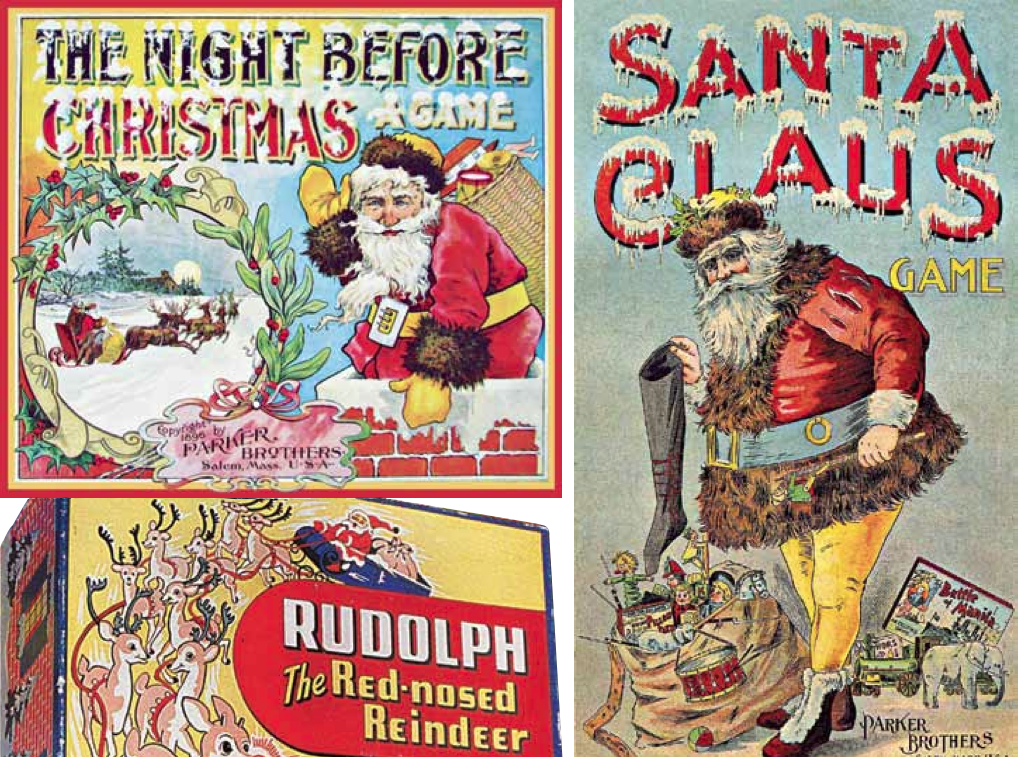

Defining ‘Christmas toys’

What is a “Christmas toy”? Must Santa Claus be on the box cover?

Au contraire, mon ami.

Sure, a kid can receive a toy any old time of year — your birthday, when you get an A, when a generous relative visits. But we greedy American children always associated Christmas morning with “Christmas toys.” When you snagged a toy on Christmas, it was thereafter remembered as a “Christmas toy.”

Media enabled this with saturation advertising on TV and in print beginning in fall. The toy section of the Sears-Roebuck catalog was an annual phantasmagoria. Store displays worked their magic as well. In December in the 1950s and ’60s, supermarkets would display toys on shelves high above the produce aisle — too high for a child to touch, but not to dream about.

The whole Santa myth involves a North Pole toy factory at which elves sing happily in an assembly line, despite the absence of salary, benefits and opportunities for advancement.

So the question of whether a toy is a “Christmas toy” is in the eye of the beholder, or more so, in the heart of the child.

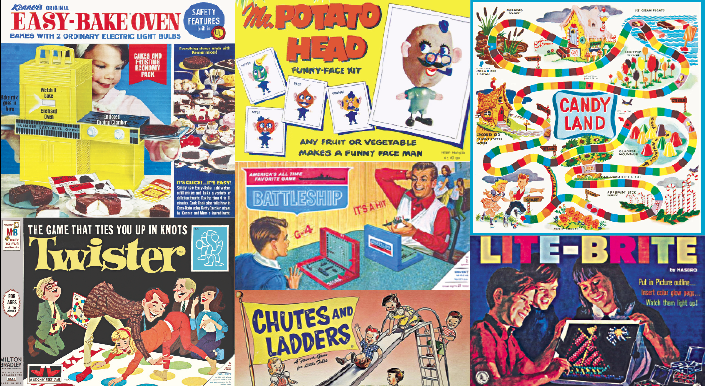

There is also the small matter of expectation vs. reality. My brother desperately wanted something called a Kookie Kamera (1968). Ideal’s toy camera was a Rube Goldberg-esque device requiring careful assembly. Two of my Irish-side uncles — one a plumber, the other a rental truck agency boss — put in overtime in assembling the complicated contraption. Alas, this was a glorified Polaroid camera — one that, to boot, didn’t work. Every photo came out pure black. What my brother got for Christmas wasn’t the wacky, innovative toy advertised, but a lesson in dealing with disappointment.

For my sister, the most coveted item one year was the Easy-Bake Oven from Kenner. It was a miniature “oven” powered by heat from a light bulb. It came with little plastic envelopes of cake mixes and frostings. My brother and I envisioned an endless supply of cakes. This never happened, of course. The “cakes” were tiny round things about 3 inches wide and 3/4-inch high. We didn’t even get to sample the first cake issued from our sister’s Easy-Bake. After carefully icing the miniature chocolate “cake” under our watchful eyes, our sister awarded it to our visiting Cousin Alfie. To this day, my brother and I still remember the slight with acute bitterness.

My folks knew I loved TV’s “The Munsters,” and on Christmas 1964, they gave me something I didn’t know existed: Remco’s 6-inch plastic dolls of Herman, Lily and Grandpa Munster. Kudos to the sculptor — the likeness of Al Lewis was amazing! (Remco made Beatles dolls that same year.) I remember grabbing a handful of chocolate “coins” (the kind wrapped in gold foil) and repairing to my bedroom, where I consumed the chocolate like medication and just stared at Herman, Lily and Grandpa for an hour straight.

But I knew all about Stick Shift Racerific (1968) from Ideal’s Motorific imprint. There were ads for it in comic books, and maybe even a TV spot. It was a sprawl- ing racetrack that took up most of the rec-room floor, on which a pair of two-speed cars raced against a wind-up clock. It had “terrific” features like the “Hairpin Turns,” the “Oil Slick” and the “Terror Turn,” which the cars had about a 50-50 chance of negotiating without “crashing” into a plastic tree and careening over a “mountain.” This mountain contained a bulky device that played the sounds of tires squealing and a crash — very high tech for 1968. Me and Cousin Alfie had the genius idea to put Vaseline on the Oil Slick for authenticity. It gummed up the cars to the point of ruination.

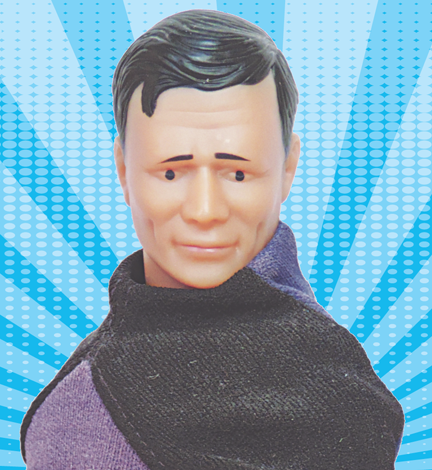

Captain Action to the rescue

One reason so many people relate to the 1983 movie “A Christmas Story” is its central theme of the little boy’s obsessive desire for a Christmas gift in the form of a Daisy Air Rifle. Nerdy Ralphie (Peter Billingsley) has fantasies in which, clad in a spangly cowboy getup, he protects his family from ornery outlaws using Daisy’s popular BB gun. In Ralphie’s mind, the air rifle becomes something more than a mere toy. It represents his very sense of self. At that tender age, we all yearn to be something, but we don’t yet know what.

The toy I wanted more than any other — my version of “A Christmas Story’s” Daisy Air Rifle — was Captain Action. He was like G.I. Joe, but with superhero costumes and accessories instead of military uniforms and accessories. Cap could become Batman, Superman, Aquaman, Captain America, Buck Rogers, the Phantom. (An interesting aside for fellow comic-book geeks: Captain Action was the first-ever DC/Marvel crossover, an important distinction usually bestowed upon the 1976 comic book Superman vs. the Amazing Spider-Man. But I digress.) During the week before Christmas 1966, when I was 8, I thought about Captain Action at every waking moment. If I hadn’t gotten Captain Action for Christmas, I would still wear the psychic scars.

But there he was on Christmas morning, with his confident expression and spiffy cowlick, sitting in a chair at his Batcave-like console, ready for, well, action. (The Captain Action console was a Sears-exclusive accoutrement, I’ll have you know.) My no-nonsense, World War II-veteran dad, who I doubt had many toys growing up, set up this little tableau for his undeserving son.

PRE-ORDER “Holly Jolly” at TwoMorrows, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and other online outlets.