Following are excerpts from a section on groovy comics presented in

“Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture” (TwoMorrows Publishing)

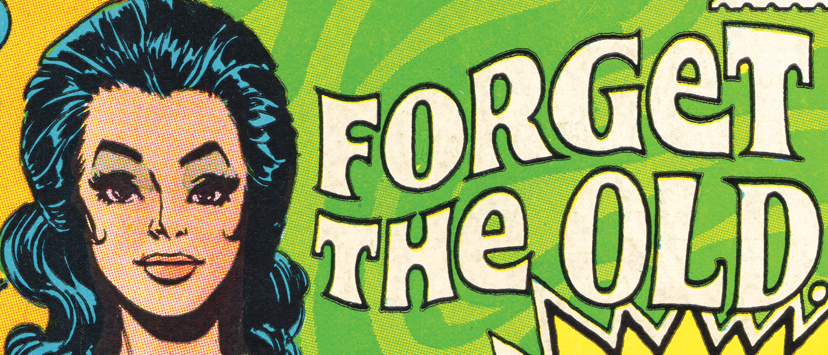

When Wonder Woman became Mrs. Peel

“Forget the old … The new Wonder Woman is here!”

So goes psychedelic lettering on the cover of Wonder Woman #178 (1968). The art, by Mike Sekowsky — once described as a “frustrated fashion artist” by fellow DC Comics artist Murphy Anderson — shows Diana Prince in an up-to-the-minute getup (complete with thigh-high boots) that would make Diana Rigg envious. Behind her is a poster in which the “old” Wonder Woman and her alter-ego, Diana (unsexy in spectacles), are crossed out with paint.

For the next 25 issues, Diana fought evil wearing mod threads; ran a trendy boutique; studied martial arts under mysterious blind instructor I Ching; and generally associated with hippies, bikers and beautiful people. Very “Austin Powers” and, for its time, revolutionary in comics.

More than any other artist then working for DC Comics, Sekowsky (1923-89) -— the founding Justice League of America artist derisively called a “speed merchant” by one inker — captured the look and sensibility of the late 1960s.

In a scene in John Schlesinger’s 1969 film “Midnight Cowboy,” Jon Voight is riding a bus to New York when he spots a little girl reading a comic. The child is clearly reading Wonder Woman #178, with that wild Sekowsky cover.

To a tiny faction of comic-book geeks, the significance of the scene is deep and resonant. Here was a comic book that reflected the changing mores of society, grabbing screen time in a movie that also reflected those changes.

The likely reality? Don’t tell those comic-book geeks, but Schlesinger’s assistant director probably sent a gofer to the closest drug store to buy any current comic book that a young girl might read. Perhaps Betty and Veronica was sold out, so Wonder Woman again saved the day.

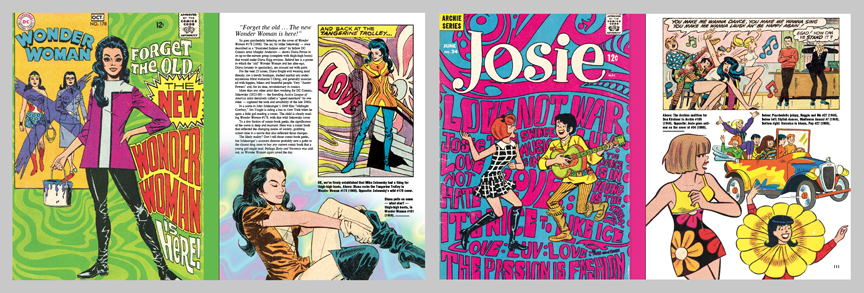

Jim Steranko vs. the old guard

As art got trippier in the 1960s, it was only natural that comic books would follow. There was one problem. Comics were then run by old-timers who dated back to the 1930s.

“I came out of a design background,” artist Jim Steranko told me in 2002. “I was also interested in film. I tried to incorporate those elements and contemporary ideas such as pop art into the comics. Up to this time, comics, I guess, were pretty stiff.

“The format of comics were the same in 1966 as they were back in 1928. I thought other things could be done in terms of telling a story.”

Case in point: Steranko illustrated a nine-issue run of “Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” for Marvel Comics’ Strange Tales.

“It was one huge serial,” he said. “I knew I had to pay this off in some spectacular fashion. But how to do it? I mean, how do you top Jack Kirby? And I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if I could imitate the climax of a James Bond movie?’ With those huge sets — you know, when Bond comes crashing into the villain’s stronghold?

“I thought it might be done by using a four-page spread that required two comic books, which you would put side-by-side in order to see all four pages at one time. In other words, I forced my reader to buy two copies.”

Marvel’s then-publisher, Stan Lee, didn’t embrace the concept — at first.

Said Steranko: “He didn’t quite get it until I said, ‘Stan, you’ll sell twice as many copies of this book as you would ordinarily.’ Then he said, ‘Jim! I love it!’ ”

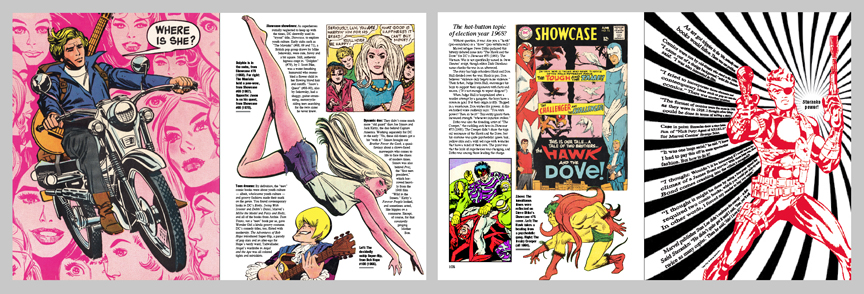

Sex, drugs and self-expression

Fredric Wertham died in 1981, so it’s possible the self-appointed Blamer-of-All-Societal-Ills-on-Comic-Books may have looked at Zap Comix.

But since there were no reports of Wertham’s head having exploded, it’s safe to assume he never read Zap.

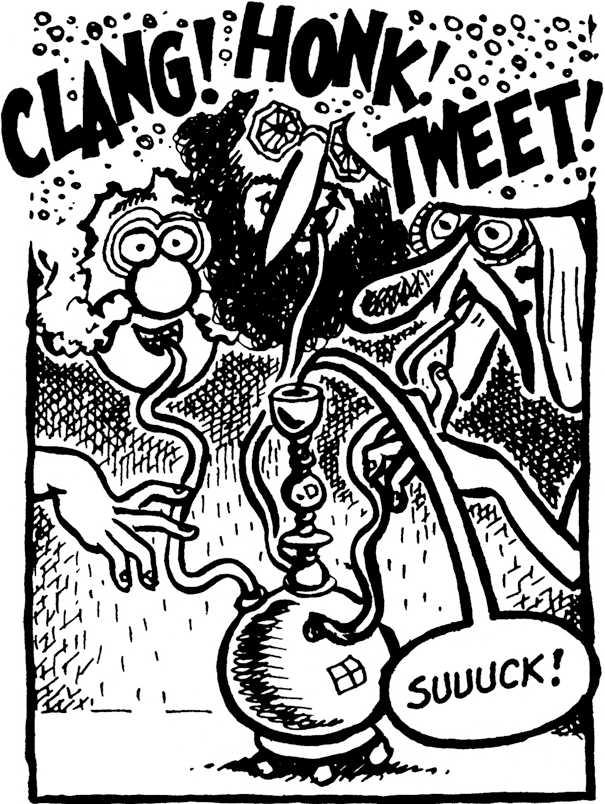

Wertham often saw decadence where there was none. But the underground cartoonists who proliferated from the mid ’60s on really did put the bad (good?) stuff in.

In the pages of Zap Comix, Snarf, Big Ass Comics, Despair, Bijou, Rip Off Comics, Trashman, Subvert Comics, Slow Death, Wimmen’s Comix, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary and many others, no sexual act was too obscene, no language too lewd, no depiction of drug use too graphic, no idol too lofty to topple.

Also, it seemed, no artist was too stoned to draw. Reading certain underground comics was like tagging along on someone else’s acid trip.

Underground comics offered total freedom to artists because they were published completely outside of the mainstream. Publishers were usually fellow hippies. Distribution occurred in head shops, urban record stores, iffy cafés and book stores, even on street corners. Advertising, and censorship, were non-existent.

Major underground scenes sprang up in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, Milwaukee and — that scene of so many scenes — San Francisco.

Mere mention of the artists’ names conjures their styles and signature characters: R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural and Fritz the Cat; S. Clay Wilson’s smirking demons; Kim Deitch’s Méliès-esque moons and cats; Trina Robbins’ inclusive feminism and reverence for comics history; Spain Rodriguez’s machine gun-brandishing Trashman; Jay Lynch’s Mutt and Jeff-like Nard n’ Pat; Justin Green’s über-brat Binky Brown; Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, with their motto: “Dope will get you through times of no money better than money will get you through times of no dope.”

These were the pen-and-pipe pioneers.

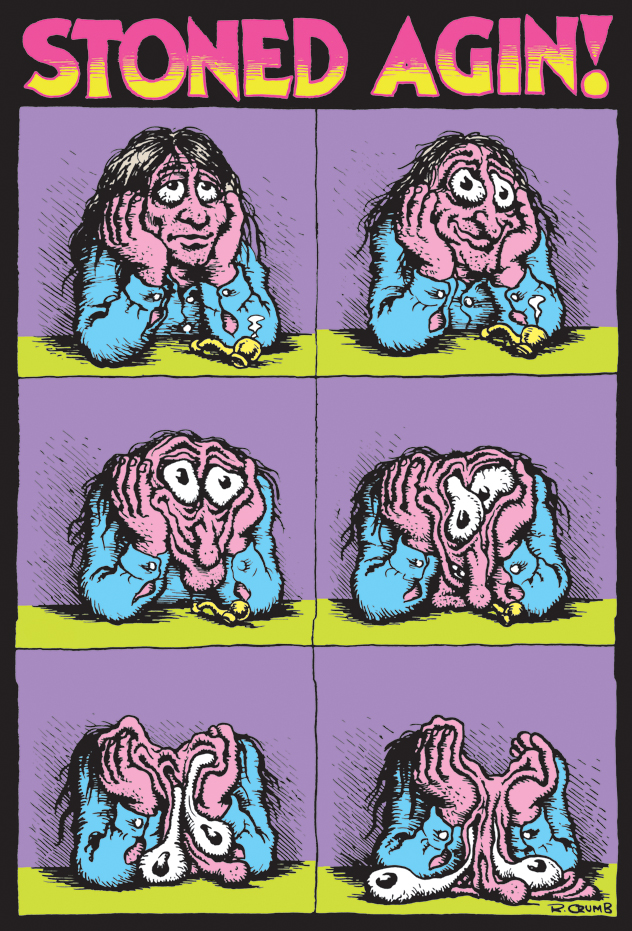

Robert Crumb: Depicting the id

The fetishy sex. The acid trips. The objectification of women. The profanity. The racism and misogyny. The self-flagellation.

These shocking elements in the work of underground cartoonist Robert Crumb certainly commanded attention.

But if R. Crumb had been nothing but a shock artist, would we remember him?

Whether or not you are personally offended by Crumb’s frequently raunchy comics, you must make certain concessions about his work. He is funny. He is accessible. He is deceptively sophisticated. (Allusions to earlier artists, and artistic movements, inform his work.) And above all, he is honest.

Crumb seems to hold nothing back. (“Depicting the id” is how his second wife, Aline Kominsky, described his process.) Crumb’s comics are frequently autobiographical, but he never sugar-coats his twisted thoughts, nor does he flatter himself physically. The Crumb you saw in real life, and the one on the printed page, were one and the same: magnified eyes peering through “Coke bottle” specs, slouchy posture, face contorted into a perma-grimace. He was, virtually, a cartoon character come to life — and the ultimate loner exacting revenge on the cold, cruel world through the printed page.

Crumb always wore his artistic influences on his ink-stained sleeve: John Stanley (Little Lulu), Carl Barks (Donald Duck), Harvey Kurtzman (Mad), even 19th-century political cartoonist Thomas Nast (a master of the shading technique known as “cross-hatching”). Thematically, Crumb’s work betrays his fixation for big-bottomed girls, as well as his lingering bitterness over his pre-fame lack of luck with the ladies. Crumb’s comics may be considered pornographic by some readers, but in the artist’s defense, they were never created with the intention to titillate.

Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Crumb apparently had an older sibling to thank for his career. “My brother Charles forced me to draw comics,” wrote Crumb in 1997. “If I didn’t draw comics, I was a worthless human being.”

In 1952, he spotted Kurtzman’s Mad #1 on a stand, but it was Basil Wolverton’s “beautiful girl of the month” cover for Mad #11 that “changed the way I saw the world forever,” Crumb wrote.

In 1962, he turned pro working for a greeting card company in Cleveland. While there, he submitted a “Fritz the Cat” strip to Kurtzman’s Mad follow-up, Help! Crumb’s work began to appear in alternative publications such as the East Village Other and Yarrowstalks.

Crumb first dropped acid in 1965. It was a milestone in his life. “The first trip was a completely mystical experience, shocking, frightening and visionary. I wanted to do it again,” he wrote in 1997. “(LSD) altered the way I drew, the arrangement of my ego, why I drew … the LSD thing was the main big inspiration of my life. I stopped drawing from life.”

Quotes from the underground

Denis Kitchen on the term “hippie”: “I had long hair, but I can tell you that we never called ourselves ‘hippies.’ That was a term the media came up with, which we found disdainful. We called ourselves ‘freaks.’ That’s where the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers came from. But over the years, I’ve come to embrace the term. I’m not ashamed to say that I was a hippie. But at the time, I would have glowered at you if you called me that.”

Jay Lynch on how his Chicago-based satire magazine led to underground comics: “At the time, it was rumored that people were smoking bananas. So I published a story about people who were smoking dog poop. The best kind was in Lincoln Park (in Chicago). The people who smoked it were called ‘****heads.’ We sold the magazine in the street. A hippie came up to me and said, ‘Thanks for the tip, man. We’ve been smokin’ dog****, and it’s great!’ I said, ‘No! That’s a satire!’ ‘No it’s not!’ We thought maybe we were overestimating our audience, so we decided to do it as a comic book.”

Trina Robbins on It Ain’t Me Babe (1970), the first comic book produced entirely by women: “Up until that point, underground comics was very much a boys’ club. The guys hung out and drank with each other and networked with each other and asked each other to be in their books. And they weren’t hanging out with us and not working with us and asking us to be in their books. And so we realized that we had to it ourselves. And so we did.”

Kim Deitch on becoming an underground comics artist: “Somebody showed me the East Village Other, which had a strip in there called ‘Captain High.’ I looked at it and figured, ‘Well, I’m no great shakes as an artist, but I can draw as good as that.’ It gave me the confidence to quit my job and go down to the Lower East Side to see what I could do in the way of art.”

SEE: ‘Groovy’ preview HERE

ORDER: ‘Groovy’ at TwoMorrows, Amazon, Target, Walmart

READ: More ‘Groovy’ excerpts HERE.