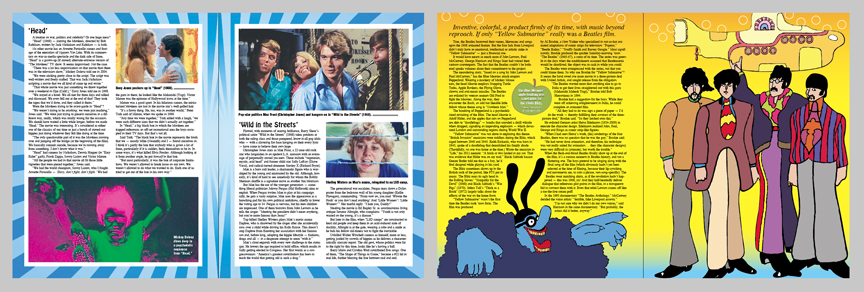

Following are excerpts from a section on movies presented in

“Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture” (TwoMorrows Publishing)

Far out flicks

You know a groovy movie when you see one. Chicks dancing in miniskirts … “liquid projection” backgrounds … quick-cut editing of wildly dancing youth at weird camera angles … seizure-inducing strobe lights … generic rock with rude fuzz guitar over shimmering Hammond … accoutrements like lava lamps, protest posters, peace medallions …

Of course, in any movie released between, say, 1966 and 1971, grooviness may occur on a dime. It could be a cop drama, a James Bond flick, even a Bob Hope movie. The protagonist — in search of a clue or a missing offspring or a drink — may stumble into a hippie nightspot, and suddenly, he’s bathed in that liquid projection. It happened all the time back then, and discovering these moments is like a treasure hunt.

But I’m talking about movies that are groovy through and through … groovy to the core. Such as? Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blow-Up” (1966) is a mod twist on Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” in which a fashion photographer in swinging London (David Hemmings) may or may not have inadvertently captured a murder with his camera. Adding to the swinging-ness is the Yardbirds (with Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page) wreaking Who-style destruction in a nightclub. The fact that Antonioni was an Italian director filming in England makes “Blow-Up” something of a voyeuristic experience.

Roger Vadim’s sci-fi comedy “Barbarella” (1968) sparked a debate: objectification of women or postmodern sendup? It raised eyebrows when Vadim’s then-wife, Jane Fonda, willingly bared all in what could be construed as titillation. Barbarella is a sex object, but Fonda deftly keeps the viewer in on every joke in this playful celebration of human desire.

Old-schoolers Jackie Gleason, Carol Channing and Groucho Marx apparently sought to impress their grandchildren by appearing in Otto Preminger’s LSD-themed disaster “Skidoo” (1968). Christopher Jones is “punished” by a trio of randy gals in Richard Wilson’s “Three in the Attic” (1968). Blake Edwards’ “The Party” (1968) stars Peter Sellers as an awkward interloper at an elite hipster bash in an ultramodern abode.

See also Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s “Performance” (1970), with Mick Jagger as a faded rock star who enters an unlikely relationship with a gangster (James Fox), and Roger Corman’s “Gas-s-s-s” (1970), a farce set in a world where everyone over 25 is dead.

I wasn’t kidding about Bob Hope. Even “Ol’ Ski Nose” made a groovy movie. In “How to Commit Marriage” (1969), Hope’s daughter (JoAnna Cameron) joins a real-life rock group, the Comfortable Chair, and follows the teachings of the Baba Zeba (Irwin Corey, sending up Maharishi Mahesh Yogi). Hope in mutton-chop sideburns, Nehru jacket and love beads is every bit as uncool as it sounds.

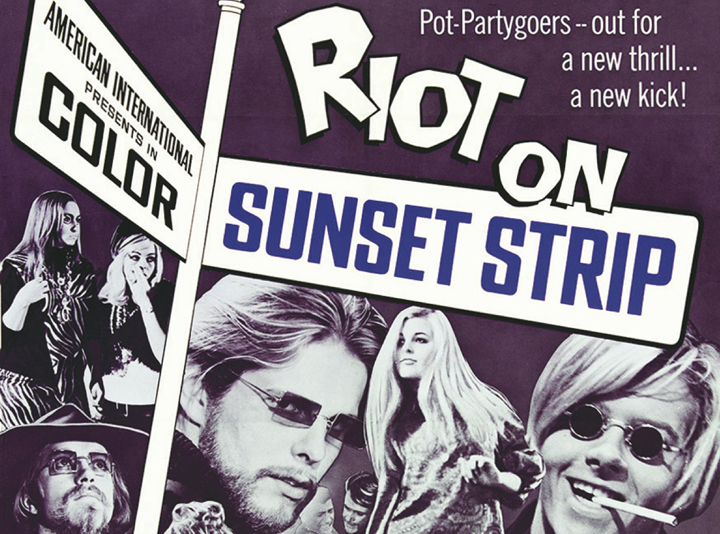

‘Riot on Sunset Strip’ (1967)

The early hippie flick “Riot on Sunset Strip” has much in common with those old, alarmist “cautionary tales” like “Reefer Madness” and “Cocaine Fiends.”

Bluntly put, “Riot on Sunset Strip” is squaresville, man.

Not only that — it doesn’t even have a riot.

There’s a lot of finger-wagging and “tsk tsk”-ing in Arthur Dreifuss’ film, which is calculated to alternately assuage, titillate and unnerve middle-aged audiences — to make the straights feel good about hatin’ on the hippies.

“Riot” — “the most shocking film of our generation!” —employs stern narration, a la “Dragnet.” The movie’s messages are: (Most) hippies are bad. Father knows best. Especially when father is a cop. And LSD makes you a really bad dancer.

‘The Trip’ (1967)

“The Trip”: An LSD movie starring Peter Fonda, Susan Strasberg, Bruce Dern and Dennis Hopper? Written by Jack Nicholson? And directed by Roger Corman for American International Pictures? That’s gotta be a slam dunk, right? Well …

Despite this high-powered talent, and the film’s catnip-y subject matter, “The Trip” is somewhat aimless.

Plot: TV commercial director Paul (Fonda) is successful but unfulfilled, and to boot, going through a complicated divorce from wife Sally (Strasberg, who should have counted her lines in the script before signing on). Paul’s overly attentive psychiatrist, John (Dern), does what any medical professional would do to treat Paul’s malaise: prescribe an LSD trip. They score acid from a friendly neighborhood supplier (Hopper), whose domicile is a non-stop pot party. Back at John’s spread — with its magnificent mountain view and indoor-outdoor pool — Paul drops the acid while John hovers, smiling and observing. (Like I said: overly attentive.) Paul freaks out, splits from John’s place and runs around, loose and bug-eyed, in Los Angeles.

That’s pretty much the whole movie.

Although, “The Trip” gets interesting when Paul, tripping out of his mind, interacts with the real world. He infiltrates a suburban home at bedtime, pouring a glass of milk for a trusting little girl whose sleep is interrupted. Later, Paul has a whacked-out conversation with a female laundromat patron who has low self-esteem. (Why else would she wear curlers and eat fried chicken in public on a weekend night?) She is amused by Paul, but screams when he “frees” her laundry from the drier.

‘Psych Out’ (1968)

You can’t visit Oz, Gotham City or Mayberry.

You can, however, visit San Francisco, just not the one in your mind. You know — the one with the dancing hippies on every block, the psychedelic posters in every window, the acid-rock bands playing in every tavern.

So here’s to an earnest, if sometimes a bit silly, movie titled “Psych-Out.” If there’s one flick that can transport you back to a groovy, late-’60s San Francisco that may never really have existed, it is Richard Rush’s “Psych-Out.”

It’s weird seeing king of Hollywood Jack Nicholson pretend to rock out on guitar, and even weirder that he stole his stage moves from Davy Jones. (Well, Nicholson did write “Head” for the Monkees that same year.)

‘Wild in the Streets’ (1968)

Flawed, with moments of searing brilliance, Barry Shear’s political satire “Wild in the Streets” (1968) takes potshots at both the ruling class and those pampered, know-it-all pop idols who — with a slavering fan base hanging on their every lyric — have come to believe their own hype.

Christopher Jones stars as Max Frost, a 22-year-old rock star who languishes in an opulent L.A. mansion with an entourage of perpetually stoned yes-men. Max is a born cult leader, a charismatic figure who is worshiped by the young and mistrusted by the old. Although, honestly, it’s kind of hard to see somebody for whom the Bobby Sherman shuffle is a signature move as another Jim Morrison.

But Max has the ear of the younger generation — something liberal politician Johnny Fergus (Hal Holbrook) aims to exploit. When Fergus invites Max to play at his campaign rally, he gets a nasty surprise; Max uses the appearance as a launching pad for his own political ambitions, chiefly to lower the voting age to 14. Fergus is nervous, but his teen children are impressed. One of them borrows from John Lennon as he tells the singer: “Meeting the president didn’t mean anything, but you’re more famous than Jesus!”

‘Yellow Submarine’ (1968)

The bombing of Pepperland is a psychedelicized revisiting of the Blitz. The head Meanie is Adolf Hitler, and the apples that rain on Pepperland are akin to “doodlebugs” — bombs that sounded a shrill whistle when dropped, signaling an impending explosion — which devastated London and surrounding regions during World War II.

“Yellow Submarine” was not alone in exploring this theme. “British Invasion” musicians were toddlers during the Blitz, which raged between 1940 and 1945. Keith Richards, who was born in 1943, spoke of a doodlebug that demolished his family abode. (Thankfully, no one was home at the time.) Wrote the musician in “Life,” his 2011 memoir: “A brick or two landed in my cot. That was evidence that Hitler was on my trail.” Black Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler told me that as a boy, he’d find shrapnel while playing in his yard. The Blitz sometimes shows up in the British rock of the period, like PTS put to music.

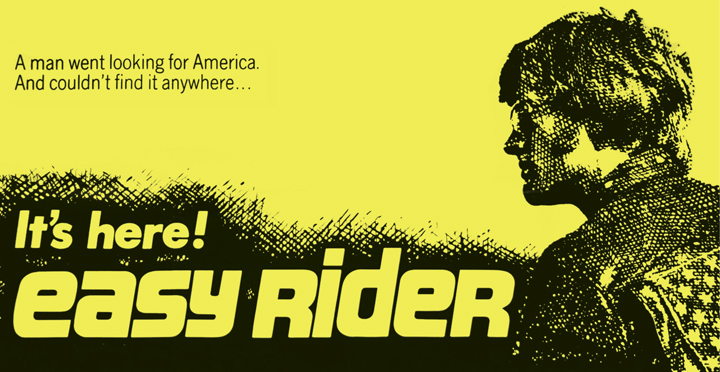

‘Easy Rider’ (1969)

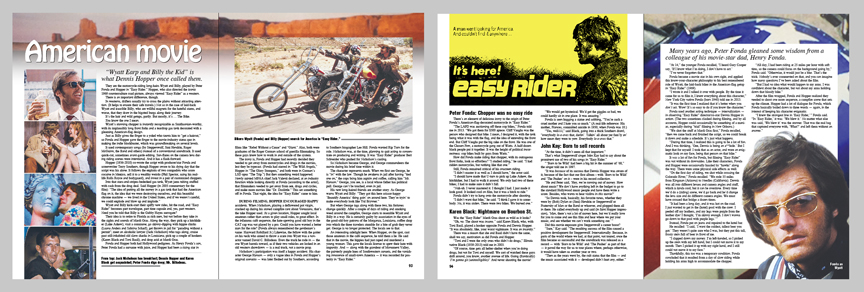

“Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid” is what Dennis Hopper once called them.

They are the motorcycle-riding long-hairs Wyatt and Billy, played by Peter Fonda and Hopper in “Easy Rider.” Hopper, who also directed the iconic 1969 counterculture road picture, always viewed “Easy Rider” as a western.

There is an important difference, though.

In westerns, drifters usually try to cross the plains without attracting attention. (It helps to ensure their safe travels.) Not so in the case of laid-back Wyatt and irascible Billy, who are willful magnets for the hateful stares, and worse, that they draw in the bigoted burgs along their journey.

It’s the hair and wild getups, partly. But mostly, it’s … The Bike.

You know the one I mean.

Wyatt’s stunning chopper is instantly recognizable as Smithsonian-worthy, with its implausibly long front forks and a teardrop gas tank decorated with a gleaming American-flag design.

Fonda on certain Wyatt dialogue: “I knew the strongest line in ‘Easy Rider.’ In ‘Easy Rider,’ it was: ‘We blew it.’ No matter what else was said, ‘We blew it’ was the stunner. That was the real bag that captured everyone with, ‘What?’ and left them without an answer.”

SEE: ‘Groovy’ preview HERE

ORDER: ‘Groovy’ at TwoMorrows, Amazon, Target, Walmart

READ: More ‘Groovy’ excerpts HERE