Following are excerpts from sections on television presented in “Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture” (TwoMorrows Publishing)

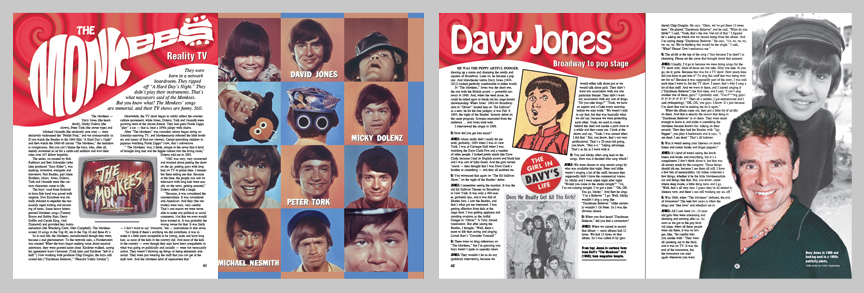

‘The Monkees’: Reality TV

They were born in a network boardroom. They ripped off “A Hard Day’s Night.” They didn’t play their instruments. That’s what naysayers said of the Monkees. But you know what? The Monkees’ songs are immortal, and their TV shows are funny. Still.

The Monkees — Davy Jones (the heartthrob), Micky Dolenz (the clown), Peter Tork (the stoner type) and Michael Nesmith (the relatively sane one) — were derisively nicknamed the “Prefab Four,” and not unreasonably so. If you watch the Beatles in the 1964 film “A Hard Day’s Night” and then watch the 1966-68 sitcom “The Monkees,” the imitation is conspicuous. But you can’t blame the boys, who, after all, merely answered an ad for a cattle-call audition and won their roles over 437 fellow hopefuls.

The series, co-created by Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider (who later produced “Easy Rider”), was madcap, inventive, energetic and irreverent. Part Beatles, part Marx Brothers, Mssrs. Jones, Dolenz, Tork and Nesmith were like cartoon characters come to life.

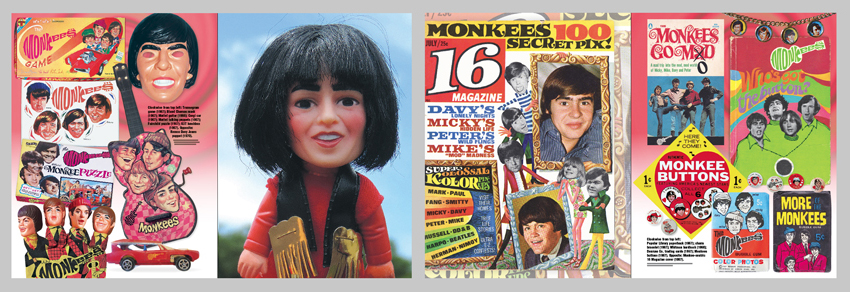

The boys’ road from fictional to bona fide band was paved with surprise. Don Kirshner was initially enlisted to expedite the necessarily rapid writing and recording of tunes. Some heavy hitters penned Monkees songs (Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Neil Diamond) and provided key instrumentation (the Wrecking Crew, Glen Campbell). The Monkees scored 10 songs in the Top 40, six in the Top 10 and three #1’s.

So in real life, the Monkees, manufactured though they were, became a real phenomenon. To the network suits, a Frankenstein was created. When the boys began making noise about musical autonomy, they were granted more clout. Kirshner walked, saying his agreement wasn’t honored. (Tork later said Kirshner “left in a huff.”) Now working with producer Chip Douglas, the boys still scored hits (“Daydream Believer,” “Pleasant Valley Sunday”).

Meanwhile, the TV show began to subtly reflect the counterculture movement, while Jones, Dolenz, Tork and Nesmith were growing tired of the sitcom format. They had guest Frank Zappa “play” a car — that is, beat a 1940s jalopy with chains.

After “The Monkees” was canceled, reruns began airing on Saturday-morning TV, and Monkeemania infected the little brothers and sisters of first-run viewers. Cereal-munching children in pajamas watching Frank Zappa? Now, that’s subversive.

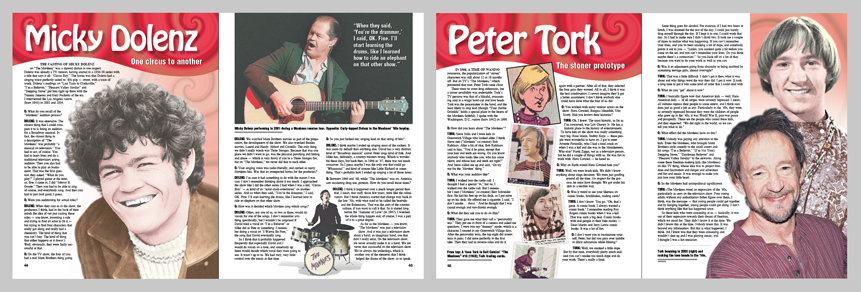

‘Monkee’ chatter

Davy Jones: “I was at Carnegie Hall (in 1964) when I was watching the Dave Clark Five. I looked pretty much like Dave Clark, because I had an English accent and I was sort of baby-faced. And the girls turned ’round — they thought that I was Dave Clark’s brother or something — and they all mobbed me.”

Micky Dolenz: “On the television show, we never actually make it as a band. We are never that successful on the television show. We’re always the underdogs, which is another one of the elements that I think helped the drama of the show, so to speak.”

Peter Tork: “These kids who were screaming at us — basically, it was out of their repression towards their dream of freedom, which we stood for. All I knew was that they were screaming and wouldn’t shut up and I was playing music, and I thought I was a hot musician.”

Michael Nesmith: “I was a Beatles fan, and that meant ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ and I was right on the same page as the producers who wanted to bring that format to TV.”

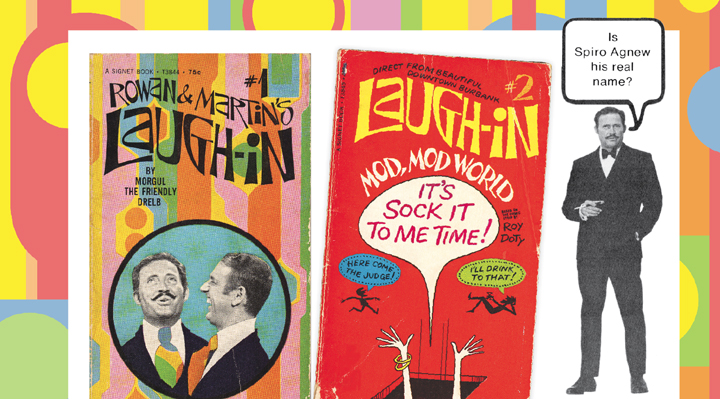

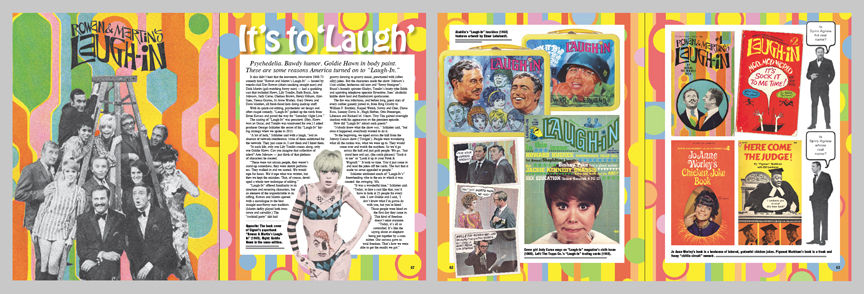

‘Laugh-In’: Hipster humor

Psychedelia. Bawdy humor. Goldie Hawn in body paint. These are some reasons America turned on to “Laugh-In.”

It also didn’t hurt that the irreverent, innovative 1968-73 comedy hour “Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In” — hosted by tuxedo-clad Dan Rowan (chain-smoking straight man) and Dick Martin (girl-watching funny man) — had a sparkling cast that included Hawn, Lily Tomlin, Ruth Buzzi, Arte Johnson, Judy Carne, Chelsea Brown, Henry Gibson, Alan Sues, Teresa Graves, Jo Anne Worley, Gary Owens and Dave Madden, all fresh-faced kids doing madcap stuff.

The casting of “Laugh-In” was prescient. (Hey, Hawn won an Oscar, and Tomlin was nominated for one.) I asked producer George Schlatter the secret of his “Laugh-In” hiring strategy when we spoke in 2011.

“A lot of luck,” Schlatter said with a laugh, “and an absence of network interference. None of them auditioned for the network. They just came in, I saw them and I hired them.

“These were not sitcom people, they weren’t stand-up comedians; they were sketch performers. They walked in and we started. We would tape for hours. We’d tape what was written, but then we kept the mistakes. That, of course, developed a whole new technique of editing.”

“Laugh-In” offered familiarity in its structure and recurring characters, but an element of the unpredictable in its riffing. Rowan and Martin opened with a monologue in the best straight man/funny man tradition. (Martin deftly played both innocence and carnality.) The “cocktail party” skit had groovy dancing to groovy music, punctuated with (often silly) jokes. But the characters made the show: Johnson’s Nazi soldier, lecherous old man and “funny foreigner”; Buzzi’s homely spinster Gladys; Tomlin’s bratty tyke Edith and squinting telephone operator Ernestine; Sues’ alcoholic kiddie show host and flamboyant sportscaster.

The fun was infectious, and before long, guest stars of every caliber gamely joined in, from Bing Crosby to William F. Buckley, Raquel Welch, Sonny and Cher, Diana Ross, Sammy Davis Jr., Hugh Hefner, Otto Preminger, Liberace and Richard M. Nixon. Tiny Tim gained overnight stardom with his appearance on the premiere episode. How did “Laugh-In” attract such guests?

“Nobody knew what the show was,” Schlatter said, “but once it happened, everybody wanted to do it.”

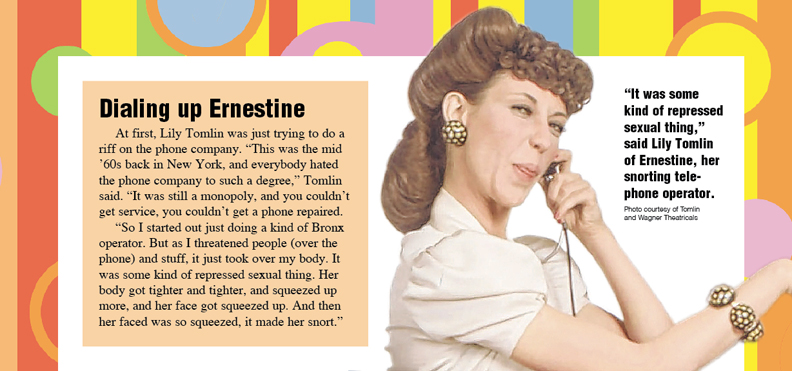

Gladys and Ernestine speak

Ruth Buzzi on ad-libbing on “Laugh-In”: “At the end of almost all the sketches, George Schlatter would say, “Remember, gang, at the end of this sketch, just continue. If somebody thinks of a funnier line than what the writers have written, we’ll leave that on.” So many times, it gave the show a look of, ‘Oh, yeah, we’re making it up.’

Lily Tomlin on creating Ernestine: “I started out just doing a kind of Bronx (telephone) operator. But as I threatened people (over the phone) and stuff, it just took over my body. It was some kind of repressed sexual thing.”

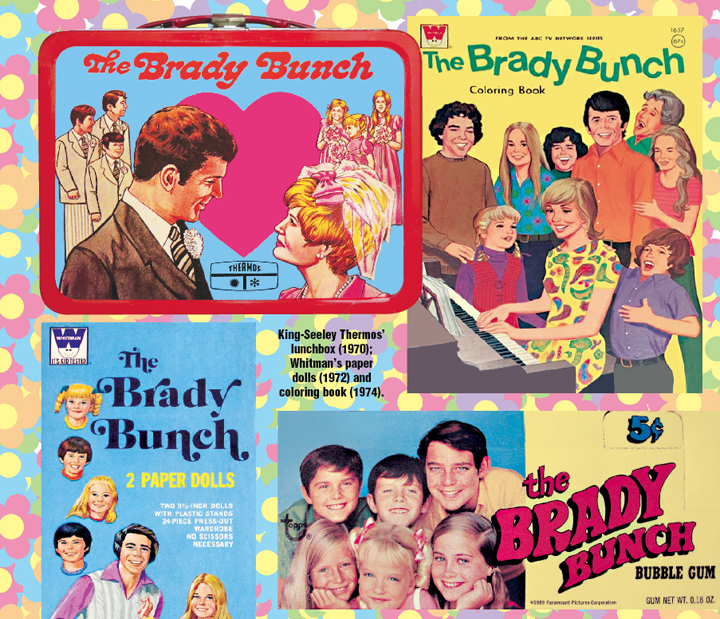

‘Brady Bunch’: (Extended) family fun

Always somewhat behind the times back then, TV still mined grooviness long after its relevance began to fade. Weirdly, it did so with family fare. “The Brady Bunch” (1969-74), a series about six kids in a blended family, got progressively groovier as the children grew older. In later seasons, they formed a pop band. In real life, the actors who played them toured as ,,, a pop band.

“The Brady Bunch” starred Robert Reed and Florence Henderson as Mike and Carol Brady, a newly wedded widower and widow with three kids each — his three brunette boys, her three blond girls — of corresponding ages, yet. The boys: hipster-nerd Greg (Barry Williams), wise guy Peter (Christopher Knight) and little squirt Bobby (Mike Lookinland). The girls: blossoming Marcia (Maureen McCormick), mildly neurotic Jan (Eve Plumb) and lisping kewpie doll Cindy (Susan Olsen). Making the meatloaf was live-in housekeeper Alice (Ann B. Davis), who apparently only removed her blue maid’s uniform in the company of boyfriend Sam the butcher (Allan Melvin).

“The Brady Bunch” was created by producer Sherwood Schwartz, whose other major contribution to culture was “Gilligan’s Island.”

“The Brady Bunch” was created by producer Sherwood Schwartz, whose other major contribution to culture was “Gilligan’s Island.”

“That was an instant flash in my head,” Passaic native Schwartz (1916-2011) told me in 2004.

“That came from just three lines in a fill-in column in The L.A. Times in 1965 or ’66. This little item said that 39 percent of all marriages had a child, or children, from a previous marriage. And, boy, the bell went off in my head. I said, ‘Since I’m a writer — and a comedy writer by designation — that opens the door to all kinds of new stories.’ Because that’s the big search for a writer. Where do you get the key to unlock new stories? And there it was, staring me in the face, with those three lines.

“I had originally written in radio. I wrote ‘Ozzy and Harriet.’ I’m an old man now. And here, not only was there sibling rivalry, there was cross-sibling rivalry, if there are kids from both sides of the fence, so to speak.

“So I went to my typewriter — I type with one finger — and I typed out the script. It was the first time I ever wrote the whole script. I was afraid someone would beat me to the punch. But nobody else saw those simple three lines.”

A ‘Bunch’ of quotes

Florence Henderson on Carol Brady: “They were saying, ‘Wear this, wear that.’ They put this big wig on me. I called it my ‘Miami bubble-do.’ I mean, it was just not me. And then they wanted me to wear aprons, and I said, ‘No, I won’t wear aprons.’ ”

Barry Williams on recording “Brady Kids” albums: “I asked, ‘What happens if half of us cannot sing?’ ‘No problem,’ I was told. ‘We’ll fix it.’ Their idea of fixing it, for those of us who were a little bit off-key, was to turn some of our microphones up and others off completely.”

Maureen McCormick on the “Brady Kids” tour: “It was hard, because some of the people couldn’t sing. And that was painful, because singing has always really been a love of mine. But we had a great time.”

Eve Plumb when asked her theory as to why so many identify with Jan, the “middle” sister: “I’m not a sociologist.”

‘Partridges’: Come on, get ratings

One year following the Bradys’ debut came “The Partridge Family” (1970-74), which cut to the chase: The Partridges were a pop band out of the box, touring the countryside in a Mondrian bus, wearing matching red-velvet costumes with lace dickeys.

Shirley Jones starred as Shirley Partridge, yet another widow, who defied child labor laws by playing nightclubs with her kids: 16 Magazine-ready Keith (David Cassidy), cutie pie Laura (Susan Dey), fast-talking Danny (Danny Bonaduce) and nondescript kidlings Chris (Jeremy Gelbwaks and Bryan Foster) and Tracy (Suzanne Crough). All were shepherded by skittish manager Reuben Kincaid (Dave Madden).

Shirley Jones starred as Shirley Partridge, yet another widow, who defied child labor laws by playing nightclubs with her kids: 16 Magazine-ready Keith (David Cassidy), cutie pie Laura (Susan Dey), fast-talking Danny (Danny Bonaduce) and nondescript kidlings Chris (Jeremy Gelbwaks and Bryan Foster) and Tracy (Suzanne Crough). All were shepherded by skittish manager Reuben Kincaid (Dave Madden).

Cassidy sang lead vocals, and Jones sang backing vocals, but otherwise, the cast couldn’t even convincingly pretend to play their instruments. Nevertheless, the Partridges had seven real-life Top 40 hits between 1970 and ’73, including “I Think I Love You” (#1), “Doesn’t Somebody Want to Be Wanted” (#6) and “I’ll Meet You Halfway” (#9), all bouncy, well-crafted pop songs.

The songs were so good that Cassidy — who became a teen idol in real life, to his chagrin — continued to perform them at his shows decades later, even as he fled the spectre of Keith Partridge.

‘Partridges’ sing

David Cassidy on Keith Partridge: “He’s totally the antithesis of who I was.”

Danny Bonaduce on ‘Partridge’ stage wear: “You’re standing there in these matching suits. Not only are they red-velvet suits, but they’ve got the big frilly collars and stuff. I think it was David Cassidy who said, ‘Oh, my God, I’m a gay pirate.’”

Shirley Jones on applying her Rodgers-and-Hammerstein-trained voice to pop: “It was like a foreign language to me.”

SEE: ‘Groovy’ preview HERE

ORDER: ‘Groovy’ at TwoMorrows, Amazon, Target, Walmart

READ: More ‘Groovy’ excerpts HERE