Following are excerpts from several music sections presented throughout

“Groovy: When Flower Power Bloomed in Pop Culture” (TwoMorrows Publishing)

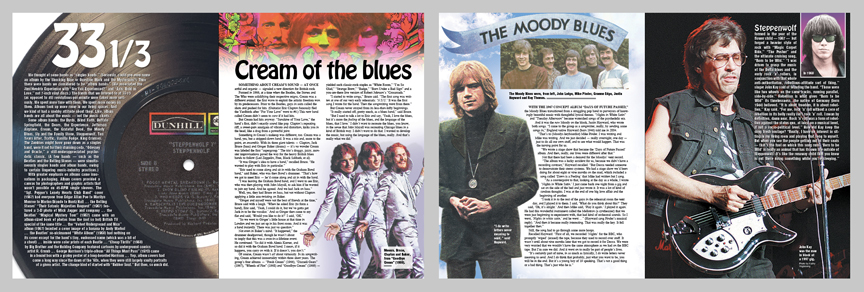

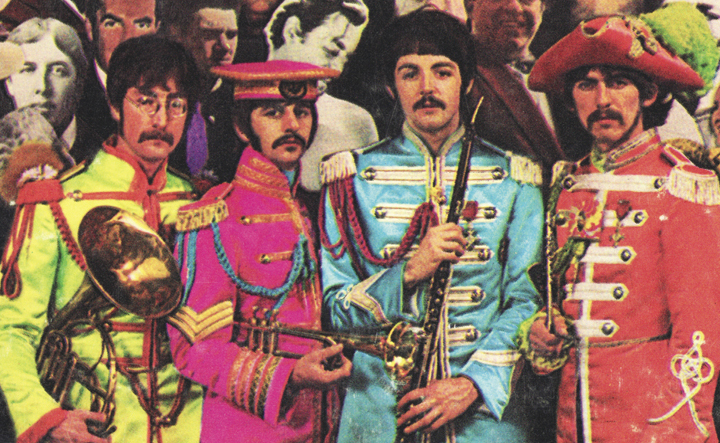

The Beatles: I’d love to turn you on

The “flowering” of the Beatles’ sound couldn’t have happened during the insane days of wanton, screaming Beatlemania.

Who can innovate, when you are four jet-lagged zombies in matching suits and haircuts, struggling in vain to hear yourselves play over a high-pitched, eardrum-splitting din?

It wasn’t until the Beatles extracted themselves from their “prison of fame” — as their producer George Martin called it — that John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr were able to, pardon the expression, let their hair down.

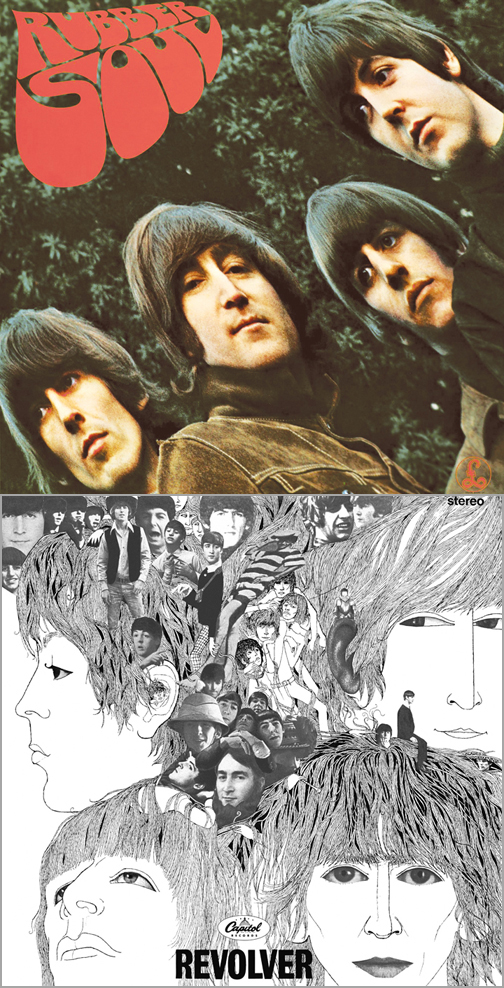

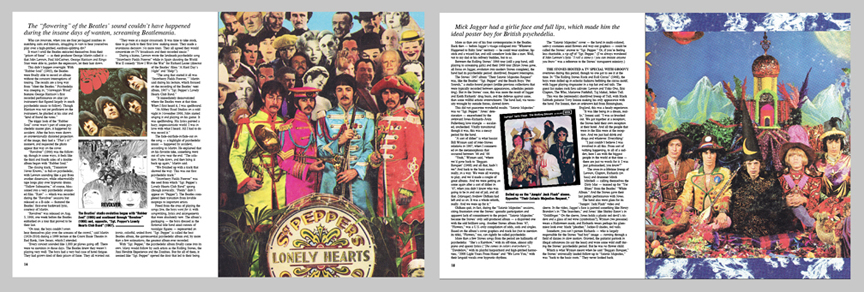

This didn’t happen overnight. With “Rubber Soul” (1965), the Beatles were finally able to record an album without the constant interruptions of touring. The results are a long way from “Meet the Beatles.” Psychedelia was creeping in; “Norwegian Wood” features George Harrison’s first recorded performance on sitar (an instrument that figured largely in much psychedelic music to follow). Though Harrison was not yet proficient on the instrument, he plucked at his sitar and “kind of found the notes.”

“Revolver” (1966) was the follow-up, though in some ways, it feels like the third and fourth sides of a double-album begun with “Rubber Soul.”

The closing track, “Tomorrow Never Knows,” is full-on psychedelic, with Lennon sounding like a guy from another dimension, while otherworldly tape loops play over hypnotic drums. “Yellow Submarine,” of course, blossomed into a very psychedelic animated film. “Rain” — which was recorded during the “Revolver” sessions but released as a B-side — featured the Beatles’ first-ever backward lyric, courtesy of Martin.

“Revolver” was released on Aug. 5, 1966, one week before the Beatles embarked on a tour that proved to be their last. “On tour, the boys couldn’t even hear themselves play over the screams of the crowd,” said Martin (1926-2016) during a 1999 lecture at the Count Basie Theatre in Red Bank, New Jersey, which I attended.

“Every concert sounded like 1,000 jet planes going off. There were no monitors in those days. The Beatles knew they weren’t playing very well. The boys had a very bad case of hotel fatigue. They had grown tired of their prison of fame. They all wanted out.

“They were at a major crossroads. It was time to take stock, time to go back to their first love: making music. They made a unanimous decision: No more tours. They all agreed they would concentrate on TV broadcasts and their recorded music.”

During a hiatus, Lennon wrote the landmark psychedelic song “Strawberry Fields Forever” while in Spain shooting the World War II comedy “How I Won the War” for Richard Lester (director of the Beatles’ films “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!”).

“The song that started it all was ‘Strawberry Fields Forever,’ ” Martin said during his lecture. “It immediately demonstrated where the Beatles were at that time. When I first heard it, I was spellbound.

“At Abbey Road Studios on a cold night in November 1966, John started singing it and playing on his guitar. It was spellbinding. His lyrics painted a hazy, impressionistic world. I was in love with what I heard. All I had to do was record it.”

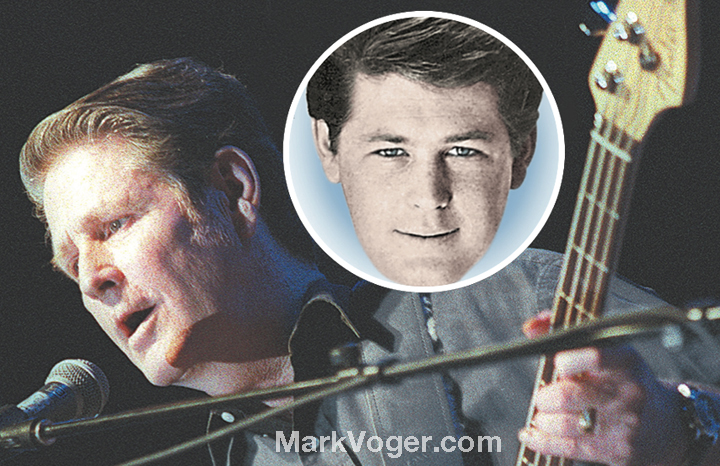

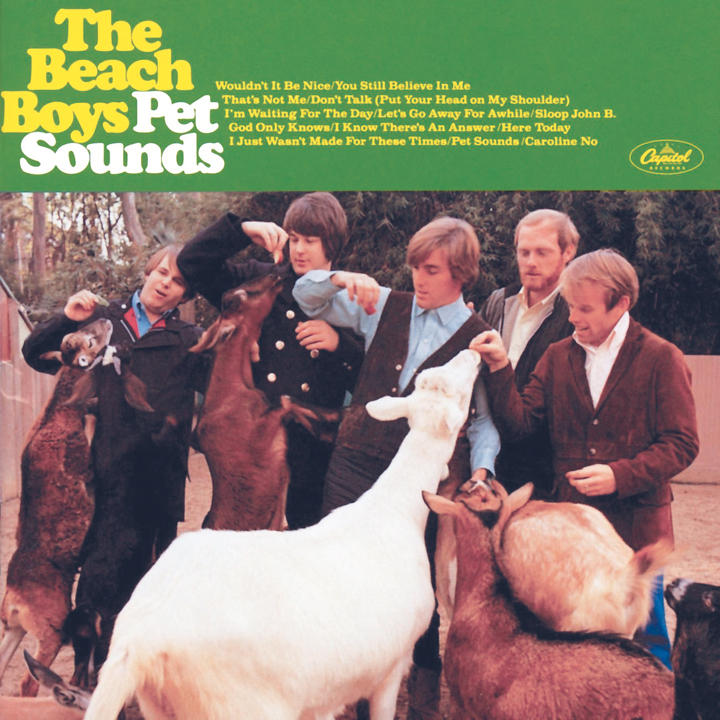

‘Pet Sounds’: Wouldn’t it be nice?

There’s much symbiosis behind the creation of art. In this way, “Rubber Soul” led to the Beach Boys’ masterpiece, “Pet Sounds.”

Brian Wilson, the architect of the Beach Boys’ sound, was inspired by the Beatles’ “Rubber Soul” to use innovative instrumentation to craft an album as a cohesive listening experience. To create “Pet Sounds,” Wilson stayed behind while the rest of the Beach Boys — Brian’s brothers Carl and Dennis, his cousin Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Wilson’s replacement Bruce Johnston — went on tour.

“Brian was the guy,” Love said. “He left the road in 1965 to devote himself to writing and producing, rather than splitting his time between writing, producing and touring. So Brian was just bursting at the seams, waiting to get into the studio. And that’s what he did. He spent all his time at home, for better and for worse — ‘better’ being musically, at the time, to develop his trade and get in with great musicians and do wonderful tracks.

“He actually developed most of the tracks while we were doing other things, like traveling and doing shows and concerts. He would be in the studio developing tracks; we would come back and collaborate. We’d do all the vocals, and we’d collaborate with some of the writing. But Brian was by far the person most responsible for the music of ‘Pet Sounds.’ ”

“He actually developed most of the tracks while we were doing other things, like traveling and doing shows and concerts. He would be in the studio developing tracks; we would come back and collaborate. We’d do all the vocals, and we’d collaborate with some of the writing. But Brian was by far the person most responsible for the music of ‘Pet Sounds.’ ”

“They were on the road, and I made all the tracks and the backgrounds,” Wilson said. “So when they got back, I taught them the voice parts, and they did all the voices.”

Was the group cooperative when they returned from the road? “They didn’t like it as much at first,” Wilson said, “but then they started liking it after they heard it back.”

“Obviously, Brian was growing faster than the speed of light,” the newcomer to the group, Johnston, told me in 2002. “I watched a lot of the tracks being recorded. Just listening to the chord changes in the tracks — the way he voiced his chords with the threes and the fives on the bottom — I knew this was way beyond anything that had ever been done in pop music that might be played on the radio.

“This was 180 degrees from ‘Help Me Rhonda.’ I just assumed that this would be another big Beach Boys album. Sometimes, ignorance is bliss. I just showed up and sang. It was one of the greatest musical experiences of my life.”

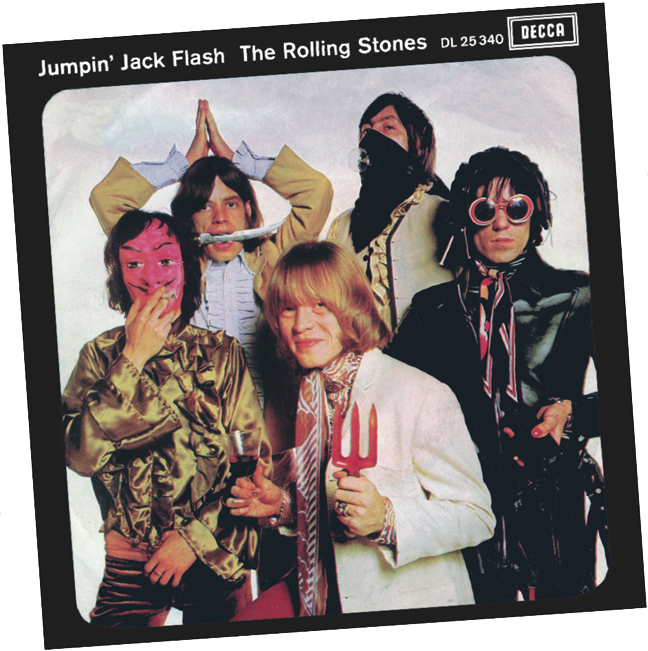

The Stones’ flowering: It’s a gas, gas, gas

Mick Jagger had a girlie face and full lips, which made him the ideal poster boy for British psychedelia.

More so than any of his four contemporaries in the Beatles. Back then — before Jagger’s visage collapsed into “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane” territory — he could wear eyeliner, lipstick and a wizard hat, and still somehow look like a man.

Between the Rolling Stones’ 1966 tour (still a pop band, still playing to screaming girls) and their 1969 tour (Brian Jones gone, all focus on Jagger, evolution into modern Stones complete), the band had its psychedelic period: shortlived, frequent interruptus.

The Stones’ 1967 album “Their Satanic Majesties Request” was, like the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper” and the Beach Boys “Pet Sounds,” a studio-bound project (unlike previous collections that were typically recorded between appearances, schedules permitting). But in the Stones’ case, this was more the result of Jagger and Keith Richards’ drug busts, and the defense against same, than some willful artistic entrenchment. The band had, via necessity wrought by outside forces, slowed down.

This did not guarantee wonderful results. “Satanic Majesties” was no “Sgt. Pepper.” Jones’ deterioration — exacerbated by the awkward Jones-Richards-Anita Pallenberg love triangle — escalated, unchecked. Vitally transitional though it was, this was a messy period for the band.

“A sort of dither” is what bassist Bill Wyman said of inter-Stones relations in 1967, when I commented on the metamorphosis that occurred between ’66 and ’69.

“Yeah,” Wyman said, “where we’d gone back to ‘Beggars Banquet’ (1968) and all that, hadn’t we? And back to the basic roots, really, in a way. We were all wanting to play, and we’d made a couple of great albums. And we were getting on some again after a sort of dither in ’67, when you didn’t know who was going to be in and out of jail, and all that. (Manager) Andrew Oldham had left and so on. It was a whole rebirth, really. And we were up for it.”

Groovy quotes from groovy musicians

Tommy James on the tremelo vocals on “Crimson and Clover”: “At the very last minute, when the record was basically finished and we were going to put on the fade, we said, ‘Let’s run the fade through the tremolo of the guitar amplifier just like we did the guitar.’ So it was basically the vocals run through the guitar amplifier with the tremolo on.”

Mark Lindsay on Paul Revere and the Raiders wearing Revolutionary War costumes: “It was like dressing up in disguise. You could get away with anything. It was just that I was kind of hiding behind this costume. The whole tenor of the band changed.” Another upside: “It’s hard to have a bad time wearing a lace dickey.”

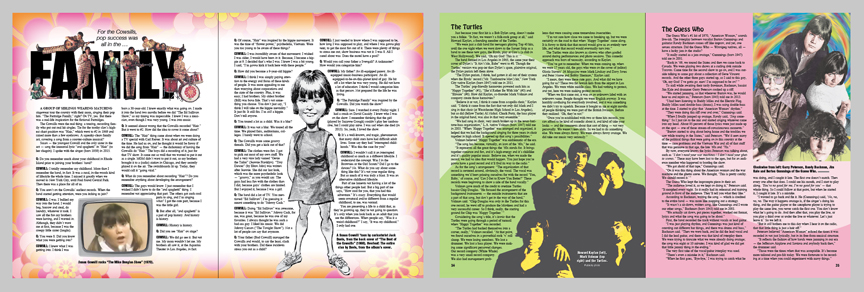

Susan Cowsill on joining her brothers’ band at age 8: “I bullied my way into the band. I would beg, borrow and steal, do laundry, whatever it took. I saw all the fun my brothers were having, and I wanted in.”

Howard Kaylan on the Turtles’ self-deprecating humor: “When we were 17 years old, the guys who were on the cover of (editor) Gloria Stavers’ 16 Magazine were Mark Lindsay and Davy Jones and Peter Noone and Bobby Sherman. I mean, they were these cute guys. And what did we have going for us? These two fat Jewish kids from the airport in Los Angeles.”

John Sebastian on the Lovin Spoonful’s influence: “Paul McCartney has been very gracious in explaining the influence ‘Daydream’ had on ‘Good Day Sunshine.’ Jimmy Page said one of the Led Zeppelin tunes was a rip on ‘Summer in the City.’ I never noticed it, but he was nice enough to point it out.”

Jack Bruce on forming Cream: “I used to talk a lot to Eric (Clapton) and say, ‘Yeah, I love the blues, but it’s more the feeling of the blues, and the language of the blues, that I love.’ I didn’t want to recreate the blues, you know, in the sense that John Mayall was recreating Chicago blues in a kind of British way. I wanted to develop the music, but using the language of the blues, really. And that’s really what we did.”

Ian McLagen on the Small Faces’ “Itchycoo Park”: “It was not all about drugs and getting high. The verses are all about education and privilege. That’s Ronnie Laine for you. He says, ‘Over bridge of sighs’ — which is Cambridge University — ‘to rest my eyes in shades of green, under dreamin’ spires’ — which is Oxford — ‘to Itchycoo Park, that’s where I’ve been.’ It’s all about privilege, money, education, Oxford. England’s green and wonderful and all this — Itchycoo Park, that’s where I’ve been. That’s what I know.”

Donovan on “Hurdy Gurdy Man”: “It was very much a mantra. In the Celtic music that I come from, they have drones, one-chord drones. In the meditation, you can chant, and it centers you. It actually can take you some of the way into this inner world.”

Justin Hayward on the Moody Blues’ “Nights in White Satin”: “It went on to really be part of people’s lives. It’s certainly part of mine, in so much as lyrically, I do write letters never meaning to send. And I do think that probably, just what you want to be, you will be in the end. But it’s a young boy of 19 speaking.”

John Kay on Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild”: ‘It’s like the runaway child that you know is out there doing something while you’re sleeping.”

Three Dog Night singer Chuck Negron on recording “Easy to be Hard”: “I sang it once, and they said, ‘We’re gonna play it back.’ And I said, ‘No, no, no, let’s go again. I’ve really got this song.’ Gabriel Mekler, who was our producer, finally said, ‘No, that’s it. You got it, Chuck. You can’t do better than this. Plus, it’s honest.’ I said, ‘Please, let me do it again.’ He played it back, and I went, ‘Wow.’ And that was it. We used the first take.”

Remembering some we lost

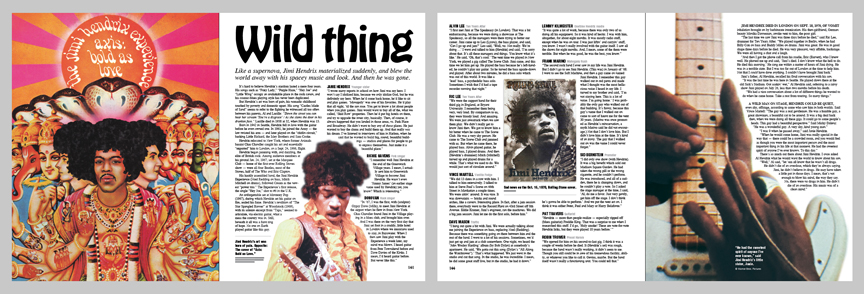

Janie Hendrix on her big brother, Jimi Hendrix: “He had the sweetest spirit of anyone I’ve ever known. To this day.”

Ray Manzarek on the death of Doors singer Jim Morrison: “I think he was just one of those guys who was genetically predisposed to alcoholism. I think in the end, that is what probably did him in in Paris: just too much drinking. That’s ultimately the tragedy of Jim Morrison, is that he started drinking, he loved it, and he couldn’t stop.”

Felix Cavaliere on “People Got to be Free,” the Rascals’ response to the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy: “The record company was really not that thrilled. They thought we were meddling in the wrong place, that it would stir up controversy. Fortunately, we had complete creative control. I was very proud of that song, because it became #1 in all of the oppressed areas of the world. We were in South Africa, we were in Hong Kong, we were in Berlin. It was really kind of an amazing feeling to know that that music got all over the world.”

SEE: ‘Groovy’ preview HERE

ORDER: ‘Groovy’ at TwoMorrows, Amazon, Target, Walmart

READ: More ‘Groovy’ excerpts HERE.