From “Monster Mash: The Creepy, Kooky Monster Craze in America 1957-1972” (TwoMorrows Publishing) by Mark Voger

![The big three — Dracula, Wolf Man, Frankenstein — were immortalized in Aurora model kits. [© Universal Studios]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-AURORA-TRIO1.jpg)

From the overview on Aurora: When, in 1960, the Aurora Plastics Corporation of West Hempstead, Long Island — manufacturers of car and airplane model kits since 1952 — conducted its first-ever survey to determine what new kits might attract customers, the answer surprised them: monsters. That old bugaboo, fear of parental outrage, gave Aurora pause. The story, whether veracious or embellished over time, goes that the company consulted psychologists on the issue, and said psychologists suggested monster models might even be a healthy thing for kids.

Famous Monsters publisher James Warren said he, too, pushed the idea to Aurora.

![Captain Company’s first-ever Aurora ad. “They looked at me like I was crazy,” said Famous Monsters publisher James Warren of the time he pitched the idea of monster kits to Aurora. [© Warren Publishing]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-AURORA-ADV.jpg)

![The surprise popularity of Aurora’s Frankenstein model kit in 1961 necessitate extra molds and overtime to keep up with demand. [© Universal Studios]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-AURORA-FRANK-125x300.jpg)

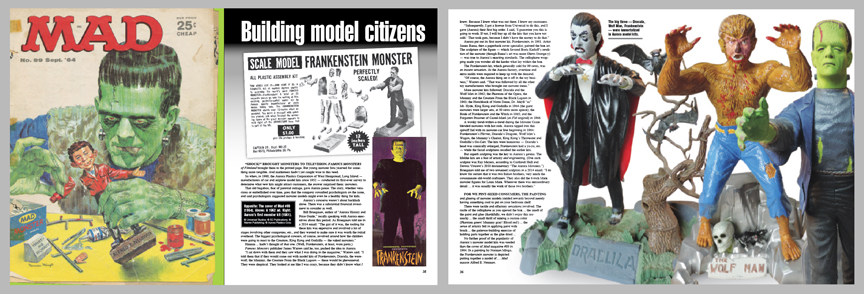

Aurora put out its first monster kit, Frankenstein, in 1961. Artist James Bama, then a paperback cover specialist, painted the box art. The sculpture of the figure — which favored Boris Karloff’s rendition of the monster (though Bama’s art was more Glenn Strange-y) — was true to Aurora’s exacting standards. The cellophane wrapping made you wonder all the harder what lay within the box.

The Frankenstein kit, which generally sold for 99 cents, was an instant sensation. At the Aurora factory, overtime and extra molds were required to keep up with the demand.

“Of course, the Aurora thing set it off in the toy business,” Warren said. “That was followed by all the other toy manufacturers who brought out monster items.”

More monster kits followed: Dracula and the Wolf Man in 1962; the Phantom of the Opera, the Mummy and the Creature From the Black Lagoon in 1963; the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Dr. Jekyll “as” Mr. Hyde, King Kong and Godzilla in 1964 (the giant monsters were larger sets, at 50 cents more apiece); the Bride of Frankenstein and the Witch in 1965; and the Forgotten Prisoner of Castel-Maré (an FM original) in 1966.

![The clearest example of Bama’s use of a movie still was his Dracula box art, which mirrored a publicity photo of Bela Lugosi from 1948’s “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein." For his Phantom box art, Bama used James Cagney in 1957’s “Man of 1000 Faces” (who was playing Lon Chaney Sr. playing the Phantom) rather than Chaney himself. [© Universal Studios]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-AURORA-DRAC-.jpg)

For we pint-sized consumers, the painting and glueing of monster models yielded rewards beyond merely having something cool to put on your bedroom shelf.

There were tactile and olfactory sensations involved. The rustle of the cellophane as you opened the box … the smell of the paint and glue (thankfully, we didn’t enjoy this too much) … the small thrill of mixing a custom color (Phantom green! Mummy gray! Blood red!) … the sense of artistry felt in applying paint with brush … the patience-building exercise of holding parts together as the glue dried …

No further proof of the popularity of Aurora’s monster model kits was needed than the cover of Mad magazine #89 in 1964. In a painting by Norman Mingo, the Frankenstein monster is depicted putting together a model of … Mad mascot Alfred E. Neuman.

![James Bama’s eerie portrait of the Wolf Man. [© Universal Studios]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-AURORA-WOLF.jpg)

Bama on why his box art became so popular: “I was the first one to do the monsters in color, other than what you saw on the movie posters. The movies were all in black-and-white, and so were the stills from the movies. Around 1958, they started showing all of those movies on television, in black-and-white, of course. So these kids had never seen these monsters in color until my box art for Aurora showed up. It was new to them.”