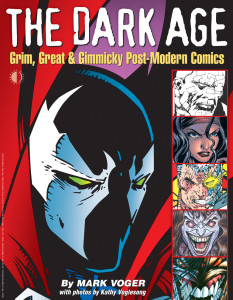

“The Dark Age” (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2006) covered the period of comics that began with a resurgence triggered in the middle 1980s, which led to an epic boom (silver-embossed covers and #1 issues sold like hotcakes, regardless of quality); then an inevitable bust; and thereafter, an incremental return to the medium’s storytelling roots (though lasting damage was done). Traditionalist that I am, I was never particularly enamored of the period, and am less so now. Heck, as I write this (in 2015), I’m reading a Rawhide Kid reprint hardback by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers that is rocking my world more than Pitt ever could. But The Dark Age yielded some masterpieces (Watchmen, Maus, Epileptic), and it’s certainly a period to remember, if only for what not to do in comics sometimes. Following are three “Dark Age” excerpts. The first, from my introduction, lays out the events of the period. (The accompanying illustrations are collages I concocted for an eight-page color section in the book.)

“The Dark Age” (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2006) covered the period of comics that began with a resurgence triggered in the middle 1980s, which led to an epic boom (silver-embossed covers and #1 issues sold like hotcakes, regardless of quality); then an inevitable bust; and thereafter, an incremental return to the medium’s storytelling roots (though lasting damage was done). Traditionalist that I am, I was never particularly enamored of the period, and am less so now. Heck, as I write this (in 2015), I’m reading a Rawhide Kid reprint hardback by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers that is rocking my world more than Pitt ever could. But The Dark Age yielded some masterpieces (Watchmen, Maus, Epileptic), and it’s certainly a period to remember, if only for what not to do in comics sometimes. Following are three “Dark Age” excerpts. The first, from my introduction, lays out the events of the period. (The accompanying illustrations are collages I concocted for an eight-page color section in the book.)

The good, the badass and the ugly

“I remember the day Superman died, back in ’92,” you may tell your grandkids one day. “It was in Superman #75. What a beauty! It was polybagged with a poster and a trading card and an obituary and an arm-band and stickers — all for $2.50! Those were the days.” To which your grandkids will look up at you with undisguised annoyance and say, “Polybagged? What the hell is that?”

![Batman relishes the sting of battle in Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986). Insets, from top right: Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, Silk Spectre and Nite Owl from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen (1986). [© DC Comics]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK2-235x300.jpg)

And happen, they did: The 900-line vote for Robin’s death … the blockbuster 1989 movie Batman … the record-setting Spider-Man #1, X-Force #1 and X-Men #1 … the rise of independents such as Valiant and Image Comics … and, of course, gimmicks, gimmicks, gimmicks. It was clearly an era unto itself, right up there with what we comic book geeks call the “Golden Age” and “Silver Age” of comics.

How would you describe the Dark Age to someone who wasn’t there? Someone for whom this period really is history? Printing-wise, comics never looked better, thanks to fantastic strides in technology. But lurid form often superseded literate content; the industry may have reached financial zeniths, but not always artistic ones. With conscience-deprived heroes indistinguishable from their adversaries, the Dark Age was typified by implausible, steroid-inspired physiques, outsized weapons (guns, knives, claws), generous blood-letting and vigilante justice. While heroes of the Golden and Silver Ages depended solely on their wits and powers to vanquish their adversaries, heroes of the Dark Age were not above flaunting a weapons advantage. Their guns got bigger and bigger. It seemed the bigger the guns, the smaller the heroes’ heads.

![Superman mourns his cousin Kara. Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 (1985). Art: George Perez. Robin goes to pieces in Batman #428 (1988). Art: Mike Mignola. Lois takes it hard in Superman #75 (1993). Art: Dan Jurgens, Brett Breeding. [© DC Comics]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK3-236x300.jpg)

Comic book “speculating” — the act of buying up comic books, not to read or to save or to cherish, but purely in anticipation of their resale profit — was hardly an invention of the Dark Age. But during that time, it took off like a Batman #600 out of Hellboy #1. What threw Dark Age speculation into overdrive was the fact that occasional flurries of media attention inspired “civilians” — people who normally never darkened the doorway of a comic shop — to scarf up copies of books perceived to be surefire collectibles. Superman, dead? Must buy copies! Cyclops and Marvel Girl, married? Must buy copies! Spider-Man #1? Must buy copies! Anything #1? It’ll put my kids through college!

![What, only three guns for Stryker’s four arms? Cyber Force #2 (1993). Art: Marc Silvestri [© Image Comics]. Lobo frags away. Lobo #8 (1994). Art: Val Semeiks, John Dell [© DC Comics]. Now, that’s a gun. Cable #17 (1994). Art: Steve Skroce [© Marvel Comics].](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK5-236x300.jpg)

But many comic books of the Dark Age commanded our attention the old-fashioned way: They earned it. Owing to the form and tone established by Miller in The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons in Watchmen, the graphic novel format thereafter retained the basic components of comics — sequential art with word balloons — but offered serious storytelling in a literate presentation. Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale — a World War II memoir in which Jews are portrayed as mice and Nazis as cats — became the first comic book to win the Pulitzer Prize. Miller topped himself with his gritty series Frank Miller’s Sin City. Once the final gimmick faded, you see, the focus of comics returned to storytelling.

The second excerpt is about a certain exhaustive (or exhausting?) miniseries that sometimes hurt my head to read, but has since acquired a nostalgic patina.

On Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985)

If the adage “less is more” is wrong — if, indeed, more is more — then DC Comics’ 1985 “maxi-series” Crisis on Infinite Earths was a lot more.

More character crossovers. More character deaths. More new characters. A story that spans from the dawn of time to the 30th century, with visits to King Arthur’s day, the Old West and World War II.

And a hot blonde in a peek-a-boo costume.

![A swishy Supes. Superman #123 (1997). Art: Ron Frenz, Joe Rubinstein. [© DC Comics]. Thor + leather jacket + ponytail = Thunderstrike #1 (1993). Art: Ron Frenz. [© Marvel Comics]. Would-be Batman Azrael shows no mercy. Batman #500 (1993). Art: Kelley Jones. [© DC Comics]. Future shock. Spider-Man 2099 #25 (1994). Art: Rick Leonardi, Al Williamson. [© Marvel Comics]](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK4-235x300.jpg)

The creators of the series — writer/editor Marv Wolfman; plotters Wolfman, Robert Greenberger, Len Wein and George Perez; penciler Perez; and inkers Dick Giordano (then a DC vice president), Mike DeCarlo and Jerry Ordway — didn’t conceal the fact that Crisis was a goal-oriented enterprise. The mission: Clean up the messy DC Universe, and do it in time for DC’s 50th anniversary.

Wolfman explained the goals of Crisis in an essay he wrote which appeared in Crisis on Infinite Earths #1.

“Change, real, permanent change, is on the way,” Wolfman promised readers. “Changes that will affect our top line of heroes. If you think even Superman is immune, you’re in for a big surprise. That’s a promise!”

By 1985 — the year in which Crisis on Infinite Earths was set as well as published — DC had established many Earths. The ‘‘Silver Age’’ Justice League of America dwelled on Earth-1; the “Golden Age” Justice Society of America on Earth-2; the JLA’s mirror-opposites, the Crime Syndicate, on Earth-3.

![Rebel superheroes were spawned — pun intended? — by feisty publishers. Insets from top left: Pitt [© Dale Keown]; Bloodshot [© Acclaim Comics]; Savage Dragon [© Erik Larsen]; Ripclaw of CyberForce [© Marc Silvestri]. Main image: Spawn [© Todd McFarlane].](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK12-227x300.jpg)

Some Earths were even seen for the first time in Crisis on Infinite Earths — just in time for them to be destroyed. (You could take this to mean that the Crisis team was still contributing to the problem, even as they were solving it.) Among Crisis-centric Earths were Earth-6, home of Lady Quark (who resembled ’80s food guru Susan Powter drained of estrogen), seen in Crisis #4, and the home Earth of perennial sad sack Pariah, seen in Crisis #7.

Feeling confused? It was hoped that these infinite problems would be solved by Crisis on Infinite Earths.

Love it or hate it, you’ve got to give Crisis its due as a gargantuan task ably met.

Sometimes, Crisis seems like a religion. When the Anti-Monitor travels back to the dawn of time in order to prevent creation itself, well, that’s pretty heavy stuff — and a long way from Little Dot in Dotland.

Many heroes were gathered in Crisis on Infinite Earths, but the true hero of Crisis is George Perez. The artist spared no effort, fudged no crowd scene, skimped on no costume.

In illustrating Crisis on Infinite Earths, Perez seemed to operate under the theory: Why draw 10 superheroes when 100 would do?

The third excerpt is about the two series that kicked off the Dark Age of Comics. One unfairly suffered because it was endlessly imitated; the other yet holds up as a touchstone of the comics.

On Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen (both 1986)

It’s a bit ironic that within a year of Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC Comics released two superhero series that proved to be the most memorable of the era — both of which wantonly brushed aside the fresh-start continuity so painstakingly established by Crisis.

![Even ‘‘Cartoon Pam’’ is fun to watch in action. VIP #1 (2000). Art: Tom Grindberg, Charles Barnett III. [© TV Comics]. Nice definition there, Selina! Catwoman #2 (1993). Art: Jim Balent, Dick Giordano. [© DC Comics]. Modeling Frederick’s of Hell. Lady Death in Lingerie #1 (1995). Art: Steven Hughes, Jason Jensen [© Chaos! Comics].](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK7-229x300.jpg)

It’s easy to underestimate or forget the impact that Batman: The Dark Knight Returns had on the medium of comics. Yes, by 1986, the industry was already well into an upswing in readership and quality. But writer/artist Miller’s powerful four-issue series (inked by Miller and Klaus Janson, colored by Lynn Varley) seduced former readers into trying comics again, and attracted new ones. The story of a bitter, alcoholic, directionless Bruce Wayne coaxed back into his old costume became a metaphor for old readers coaxed back into comics.

Batman, and Batman fans, were born again.

Beginning in 1979, Miller’s brief run penciling Spectacular Spider-Man won the attention of then-Marvel head Jim Shooter, which led to Miller winning the assignment to pencil Daredevil. Before long, Miller was plotting and then outright scripting the exploits of the blind, red-clad “Man Without Fear.” With Daredevil, Miller first exhibited his penchant for reinventing a superhero by basing him in a no-nonsense reality. Under Miller’s aegis, liberties were taken. One of the most memorable was the introduction of DD’s Irene Adler, foxy ninja Elektra.

![Luscious –and handy with a sword. Gen13 #5 (1995). Art: J. Scott Campbell [© Aegis Entertainment]. Silver Sable gets a leg up. Silver Sable and the Wild Pack #1 (1992). Art: Steven Butler, Jim Sanders III [© Marvel Comics]. Heroine – or exotic dancer? Shadow State #2 (1996). Art: Dave Cockrum, Frank McLaughlin [© 2006 Broadway Comics].](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK8-233x300.jpg)

“Batman is as good and pure a superhero as you can find,” Miller told Kim Thompson in The Comics Journal #101 (1985). “He’s actually a good character, as compromised as the idea has become, as corrupted by shifting political attitudes and 50 years of monthly publication. … What I’m trying to demonstrate in the Dark Knight series is that superheroes do come from a good idea, by portraying the city in somewhat more realistic terms and showing … the way I think things actually happen in society and why they happen.”

These many years later, some of The Dark Knight Returns seems cliched or old hat. At one point, Batman actually tells a baddie: “I’m the worst nightmare you ever had” — a line that may have sounded fresh in ’86, but today would prompt Bruce Willis to demand a rewrite. Even the word ‘‘dark’’ itself became so overused in comics in the ensuing years.

So keep in mind that a lot of what Miller was doing had never been done before in comics. The tone, if not the quality, of The Dark Knight Returns was recycled in so many comic books to follow that the original was, inevitably, watered down.

![A collage from the back cover of “The Dark Age” (minus the type) featured Superman in art by Ron Frenz and Joe Rubinstein; Catwoman in art by Jim Balent; Dr. Manhattan in art by Dave Gibbons; Lobo in art by Val Semieks and John Dell; and Batman in art by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley [© DC Comics].](https://markvoger.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MVCOM-DARK9-300x282.jpg)

Like Crisis, Watchmen was set in 1985, but not the 1985 we remember. Richard Nixon is still president; superheroes are outlawed; everyone drives floating electric cars and smokes weird cigarettes; and the international political scene points with dread to a pending Armageddon. When someone begins killing off former superheroes, their surviving colleagues commiserate, reopen old wounds — and suit up.

The series was universally lauded for its exploration of the human foibles of costumed heroes.

“I think the timing of it was very apt,” Gibbons told me in 2005.

“Because it hit a point where comics were going through a certain, slightly moribund kind of phase. It jerked everything up to date. It put a lot of attention on comics. It also coincided with Frank Miller’s wonderful Dark Knight Returns. The two things kind of went hand in hand.”

Order “The Dark Age: Grim, Great & Gimmicky Post-Modern Comics”