His comics were ‘written for everybody’

It was in 1939 that 16-year-old Stanley Lieber — better known as Stan Lee — got his first job in comics. It’s a job that, in one form or another, he never really let go of.

Born in New York City in 1922, Lee was promoted to editor at Timely (later Marvel Comics) in 1942, after his old bosses, artists Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, defected to National (later DC) Comics.

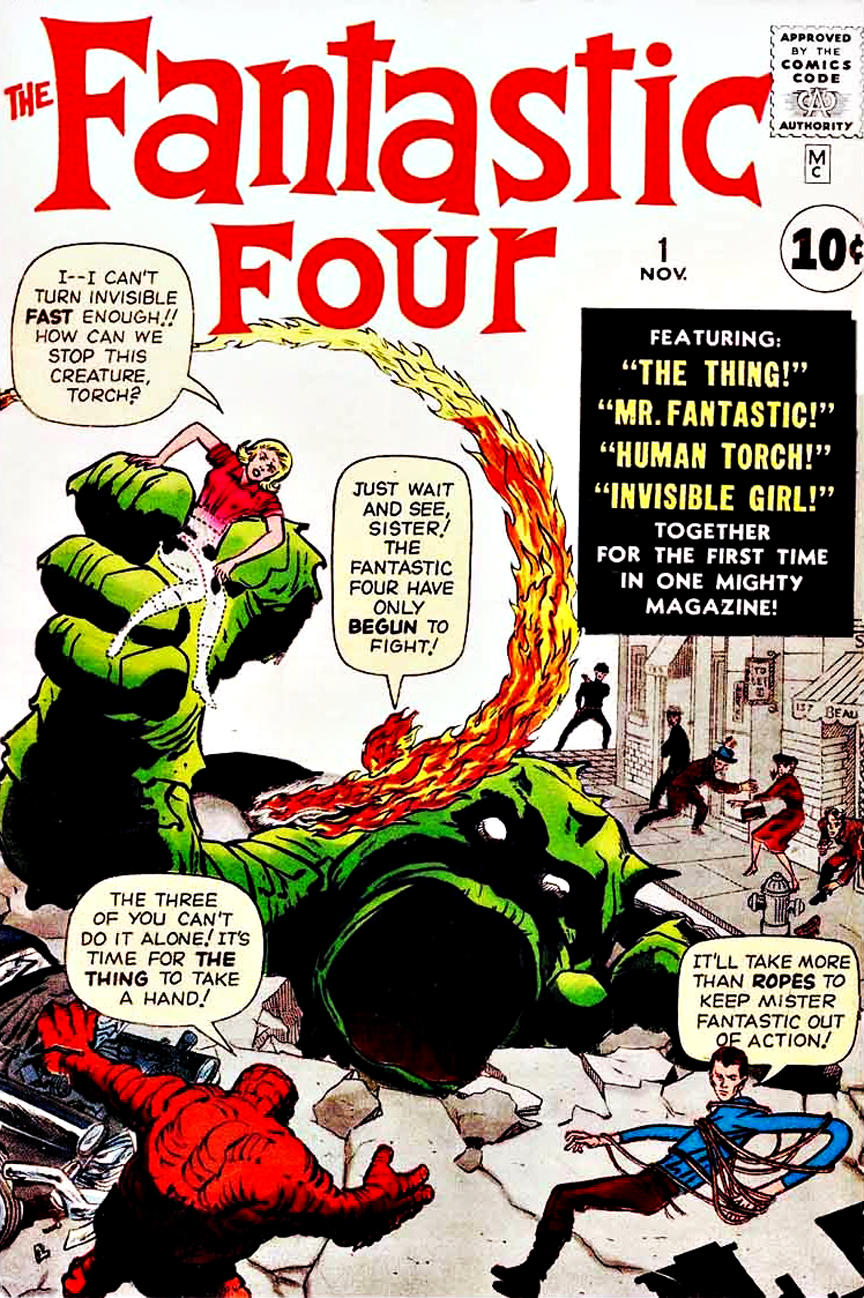

But it wasn’t until 1961 that the pivotal moment in Lee’s career happened. Planning to leave the comics field, Lee threw caution to the wind and wrote a comic book the way he’d always wanted to. The result, Fantastic Four #1, was a different kind of comic book in which characterization was as important as action. FF#1 was an instant hit, and triggered a renaissance at Marvel Comics.

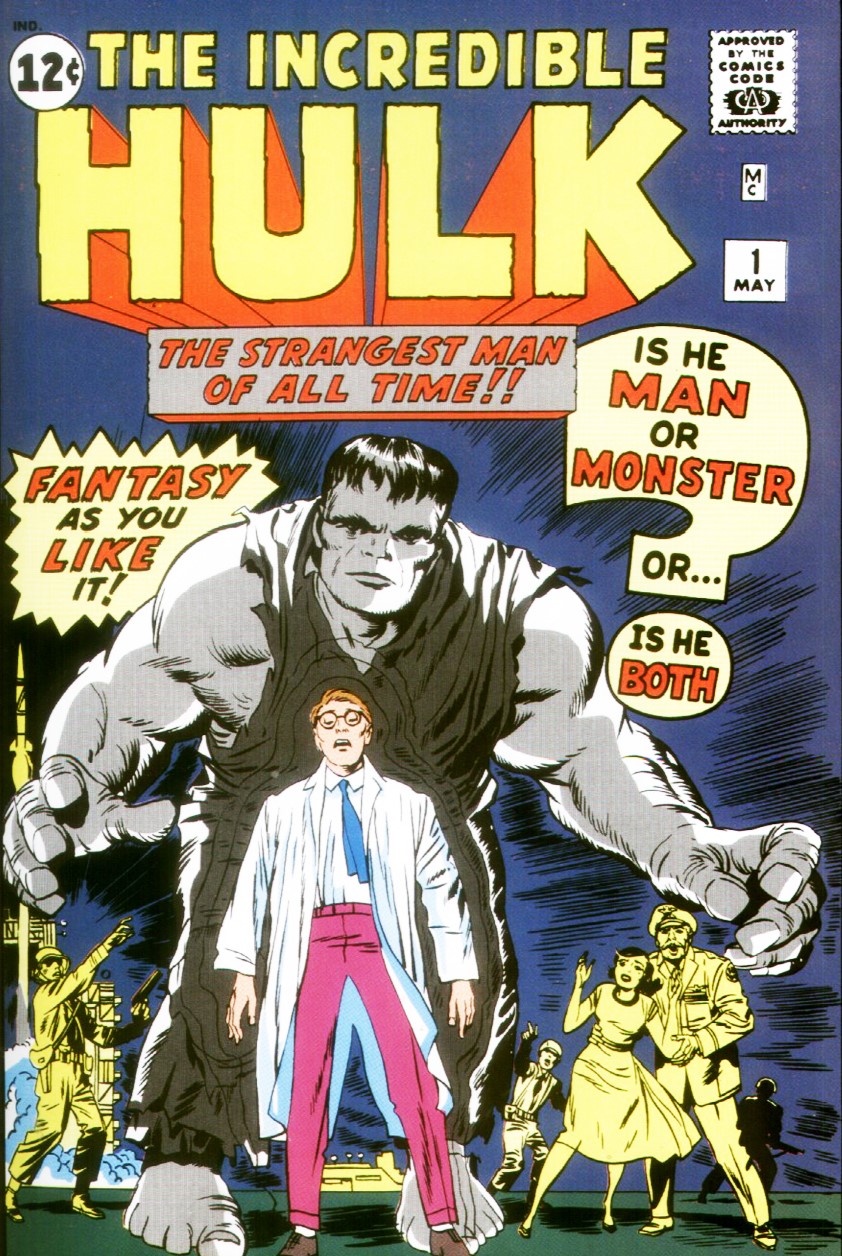

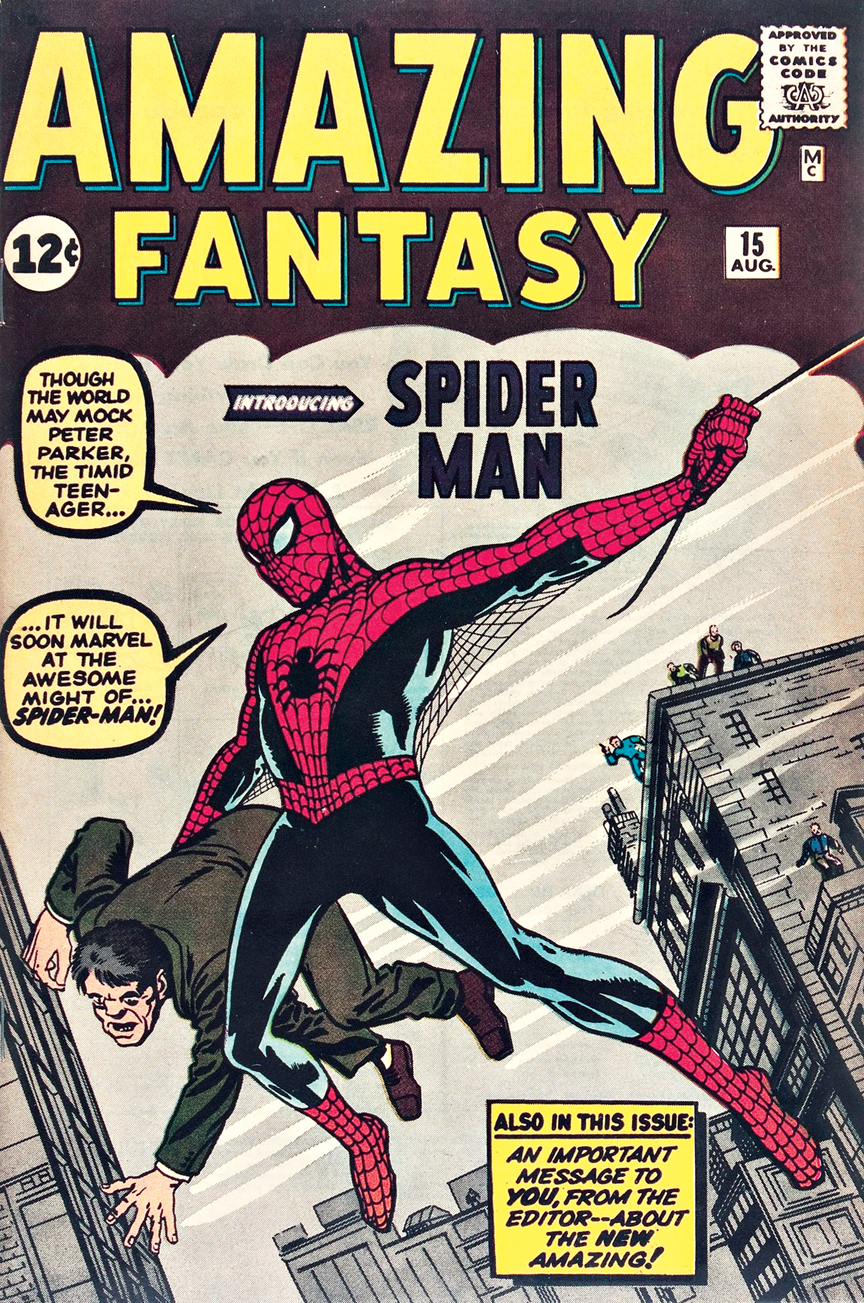

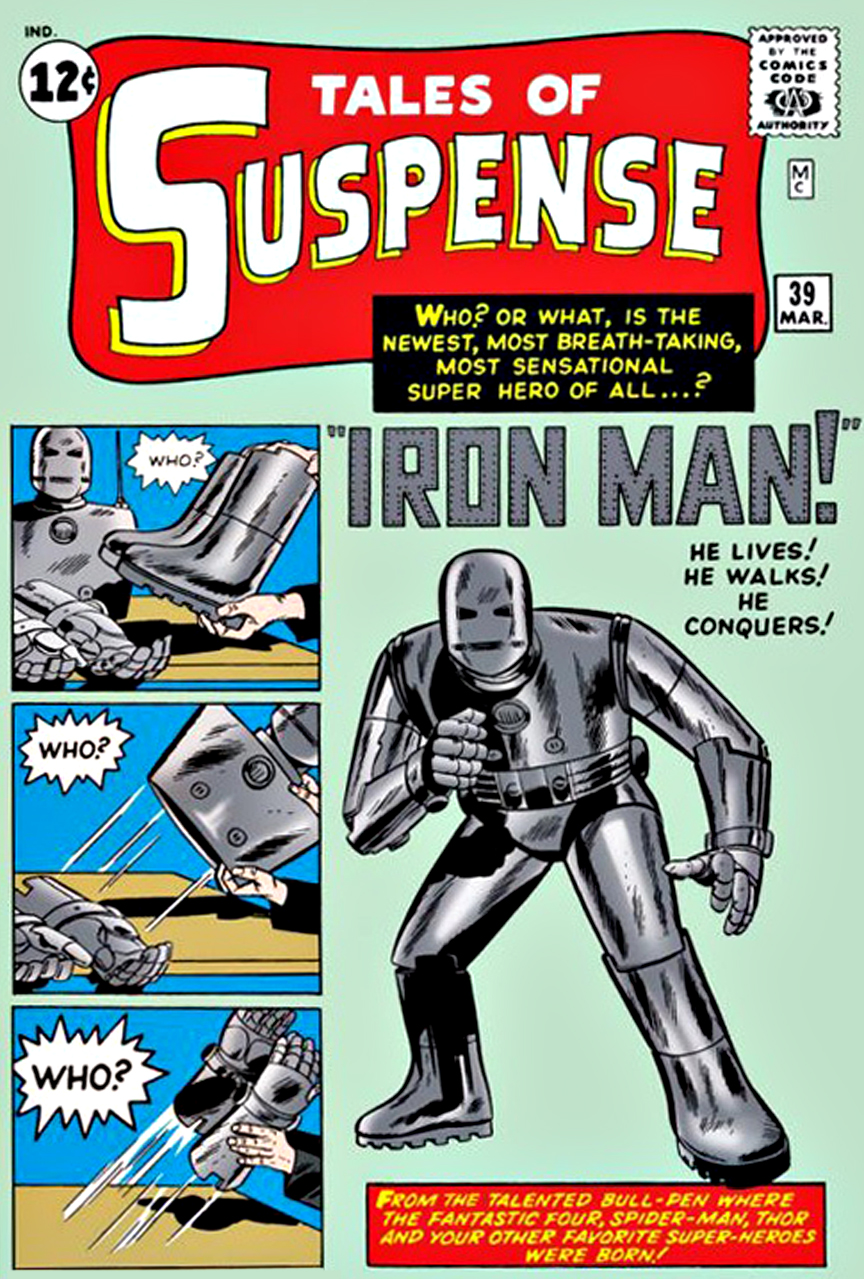

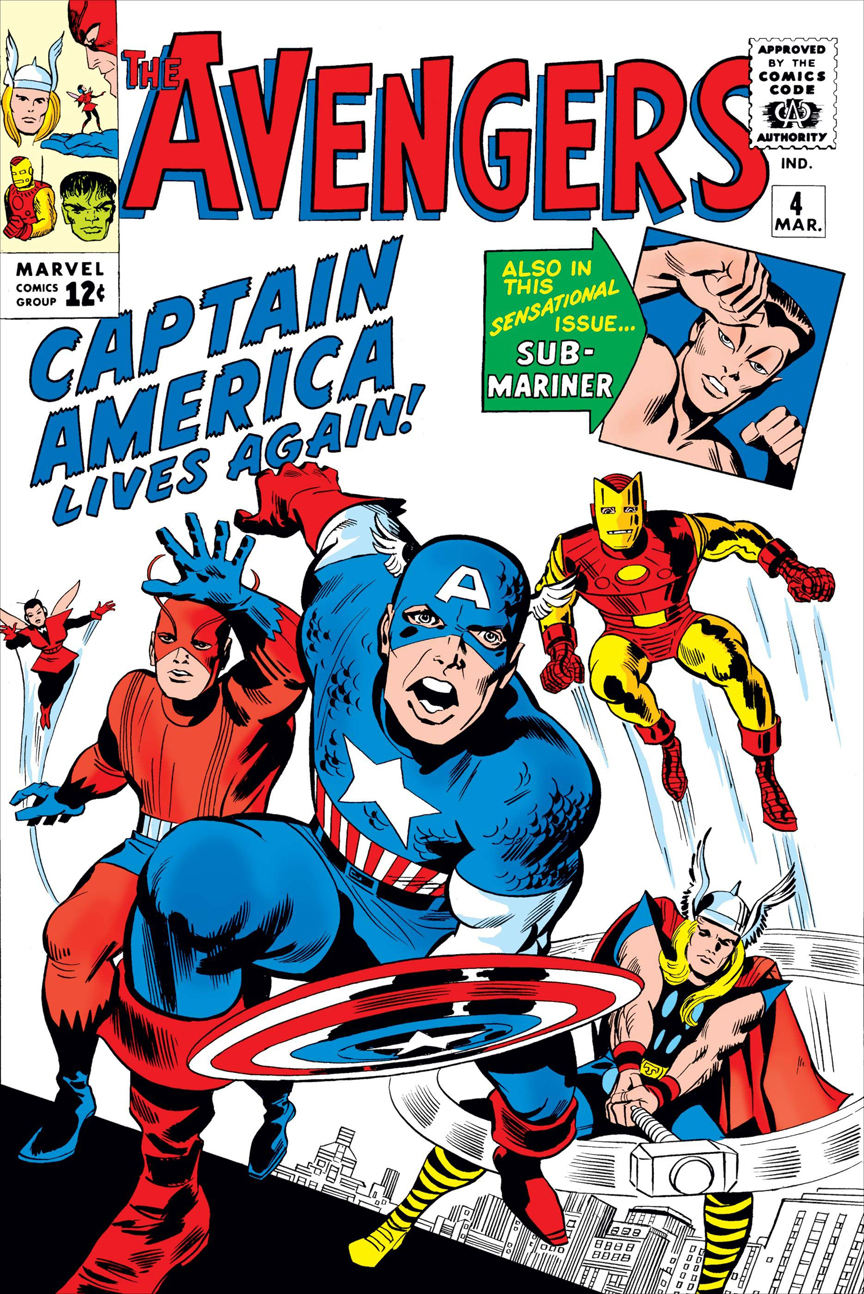

Thereafter, Lee and his artists — chiefly Kirby, Steve Ditko, Dick Ayers and Don Heck — set about creating the “Marvel Universe” : the Hulk, Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, Iron Man, Daredevil, Thor, X-Men and many more.

To mark Lee’s passing today at age 95 in Los Angeles, here are excerpts from a 1993 interview I did with him.

Q: Do you have a vague idea how many characters you’ve created? Including obscure sub-plot characters like, say, Mrs. Watson?

A: No, I really have no idea. And I even created so many characters before Marvel over the years, when we were just doing these ordi1nary magazines. I created western characters, romance characters, humor characters. In humor, there were Nellie the Nurse and Millie the Model and My Friend Irma. Hundreds of them. Well, I didn’t create My Friend Irma — that was based on a TV show. And there was Georgie and Willie and Freddy. It goes on forever. Then in the war stuff, there was Combat Casey, Combat Kelly. And with westerns, there was the Black Rider, the Two-Gun Kid, the Rawhide Kid and on and on. The animated cartoons, there’s no way to keep count. There was Silly Seal and Ziggy Pig and Posty the Pelican. It just goes on. And then there’s all the incidental characters. Super Rabbit (laughs).

Q: Those early Marvel books were “braided,” story-wise, and you wrote them simultaneously. How did you juggle all of those plots and sub-plots? Did you plot a given book a year in advance, or write them month-to-month, spontaneously?

A: I was never smart enough to do it a year at a time. Very often — and I think it was one of the things that made the stories work well — I would look at a drawing and get a totally different idea than what the artist originally had in mind. I mean, obviously, I couldn’t change an action. If a guy was running, I couldn’t write it as if he was sitting in a chair. But the artist might have him running as though he’s chasing somebody, but I may have written it as if he were running for a different reason. I would alter it, and that’s what made it fun for me. I would alter the story as I was writing it.

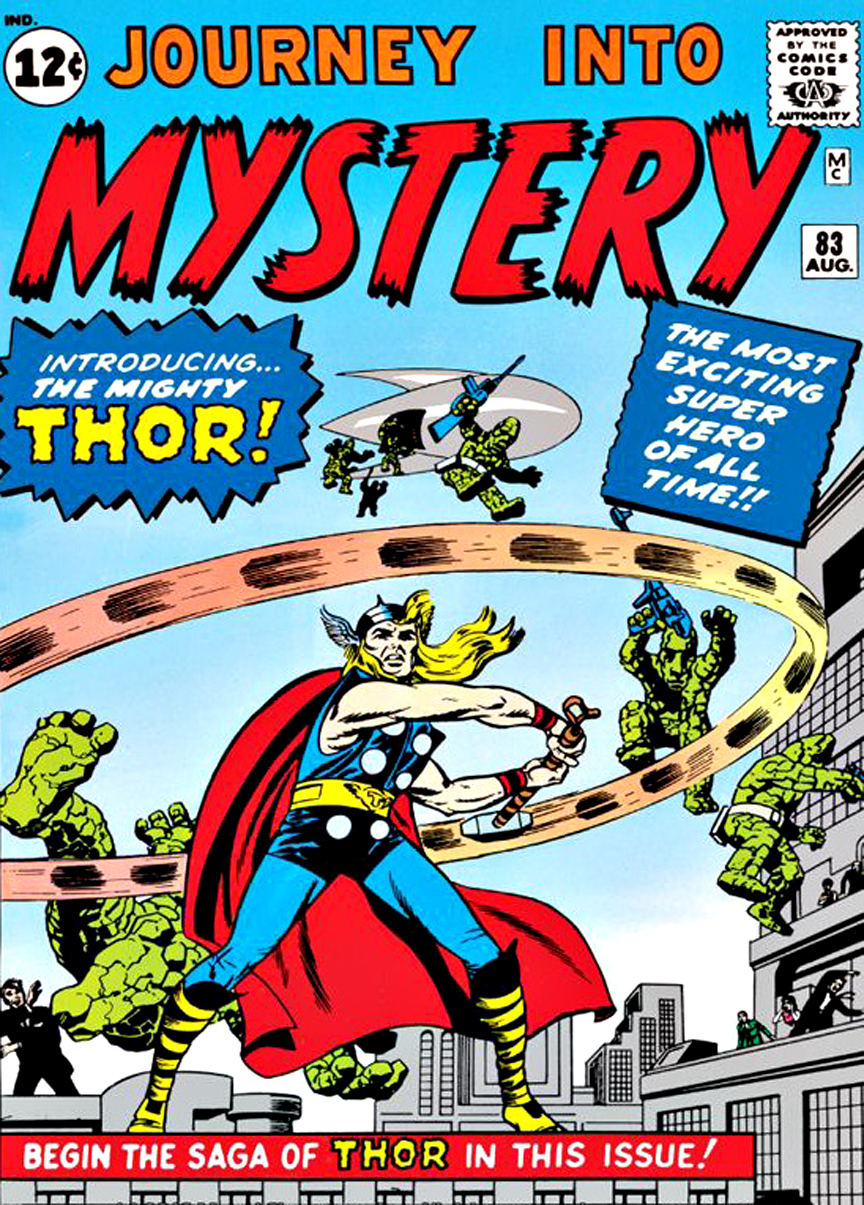

“Journey Into Mystery” #83 (1962)

Mostly, those little things that happened in one issue and cropped up in another issue, I would say happened as often because the artist remembered something from the last issue as I did. But, each time I had to write the copy — because I have such a bad memory — each time I got the artwork for a book, I would quickly go through my carbon and look at the script I had written for the previous book. Because, I didn’t remember it at all. I would read the script quickly, and that refreshed my memory. And in reading the script, I would say, “Gee, Flash said something,” or “Harry Osbourne said something here. It would be great if I could comment on it in the next issue.” And then I would look through the artwork and see if there was a place I could comment on it. But if I hadn’t sat down to read the carbon of the last script, I never would have remembered it.

I never planned more than one issue ahead. I don’t have that kind of mind. I just work one issue at a time. In fact, it’s more fun for me if I don’t know what’s going to happen. I think that’s the reason, really. I could have planned ahead, of course, but then I’d be bored. Like, when I do the Spider- Man newspaper strip, I have to do that many weeks and months ahead. And I find that it bores me a little bit, because I know what’s happening. When I was doing the comic books, I was never sure what was going to happen, and that kept my interest up.

Q: A lot of the artists from the early days felt they’d been taken advantage of, financially and copyright-wise. But one gets the impression you didn’t have all of your eggs in the creative basket. That you had business sense.

A: No. Actually, I must say, I think that all of my eggs were in the creative basket. I had as little to do with the business end of the company as possible. The only business dealings I had was, I would tell our publisher at the time which books I thought would sell and which I thought wouldn’t. But not as far as what people come to mean by business — the amount of books we distribute or what price or the cost or dealing with the printer or anything like that. The only business thing I always tried to be involved in was trying to get the artists and writers and editors and whoever was on staff, trying to increase their pay. I always felt that people were tremendously underpaid in comics. For the amount of talent that artists had and the amount of work that went into writing scripts — at least, writing them the way I felt they should be written. When you would compare what a writer of a comic book would get to what a writer who sold a novel or a screenplay or a television show were getting, or what an artist would get for doing an advertising drawing or a painting, I always felt that the rates were embarrassingly low. But the people at the business end of our company would tell me we were paying as much as we could, and if we paid any more, we’d go out of business or we couldn’t afford to do the books. So it was always a constant battle between me and them. It was a friendly battle, but a battle that never ended.

Q: Do you remember the moment you knew it was finally cool to work in comics? When comics were “in”?

A: The only thing that taught me it was big, bigger than I thought, was after we did the Fantastic Four and then we did the Hulk and then we did Spider-Man and by that time, the mail began to overwhelm us. We had never received fan mail, really, prior to that time. Suddenly, to be getting literally hundreds and hundreds of letters a week from all over, some written in crayon by young kids and some typed on electric typewriters by college students, I suddenly began to realize that there was a world out there that was really paying attention to these little comic books.

Q: Were you surprised at the number of college students and military people who wrote to you early on?

A: No, not at all. I would have expected it. I was rather disappointed we didn’t have more brain surgeons and senators writing to us. These stories were written for people, not for little children. They were written for everybody. In fact, the formula that we used was to keep them simple enough and understandable enough and unobjectionable enough so that any youngster could read it and enjoy it, and to keep them exciting enough and sophisticated enough and intelligent enough for an older reader. I never thought of an age group when I wrote these stories. I just thought of trying to write something entertaining.