The movie that made me love Dan Duryea

The independently produced noir masterpiece “The Burglar” could not have been made within the Hollywood studio system. There would be too much fretting, too much meddling, too much adhering to prevailing standards. “The Burglar” is its own movie, through and through, and it fires on all pistons. The script, casting, direction, cinematography, editing, music, set design and location scouting are all dead on.

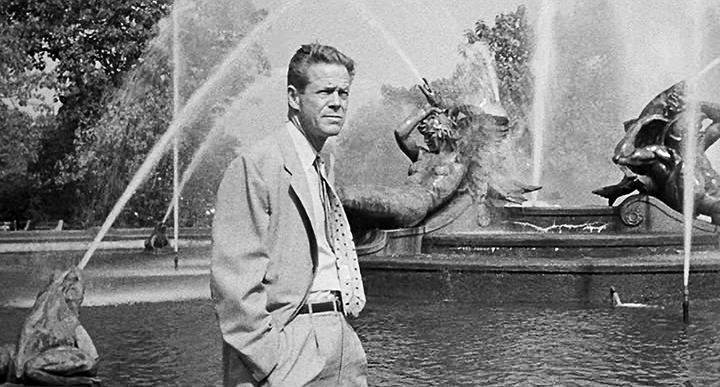

It’s also the movie that made me fall in love with Dan Duryea.

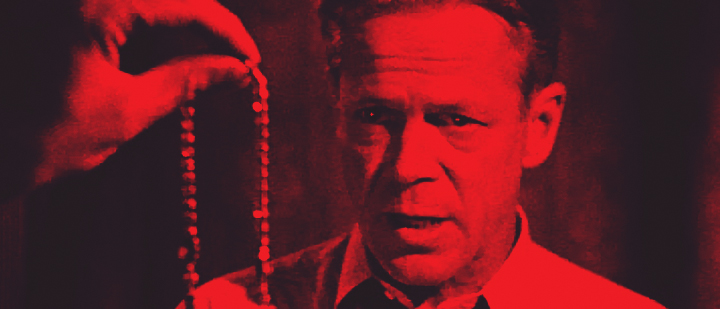

For years, when Duryea would show up in a late-’40s noir such as Fritz Lang‘s “Scarlet Street” or Byron Haskin’s “Too Late For Tears,” I would think, “Not that guy again.” Him, a tough guy? In those stupid hats and bow-ties that look like something out of Andy Hardy? His characters were always so skeevy. And yet, trusted noir sources (such as TCM host Eddie Muller and novelist Wallace Stroby) always vouched for Duryea.

I didn’t get it. Then I saw “The Burglar.”

Paul Wendkos’ engrossing film in stark black-and-white was released in 1957, a decade after Duryea’s better-known movies, by which time the actor had aged like a fine wine. This Dan Duryea wears a face with a few more lines in it, his acting more internal.

The guy is top-billed in “The Burglar,” but for a long while, he doesn’t utter a word. People around him do the talking, and yet, every eye is on Duryea. Such is his magnetism — not to mention, the craft of the scriptwriter (David Goodis, from his novel) and director. The actor’s first words in the movie are mundane: “30 seconds,” he finally says, glancing at his watch during the heist. But he’s already said so much with his presence alone.

It’s striking how modern “The Burglar” still seems, and how unconcerned with then-compulsory movie templates. The film begins — not with a studio logo and fanfare music followed by title and credits — but with a newsreel. In other words, We are thrown into the movie immediately. The practice of starting a movie without titles became increasingly commonplace into the ’70s — Francis Ford Coppola‘s “The Godfather” comes to mind as an early offender — but not in the ’50s.

The typographical design of the title and credits, when they finally appear, also break norms. Type is superimposed over action, with every word in lower case — title, names and all. It is artsy and, seeing it now, somehow timeless. Heightening the effect, the titles are sharply punctuated by Sol Kaplan’s sometimes shrill (in a good way) score.

So out of the box, we’re putty in this film’s hands.

On a personal note, I’m also struck by the fact that “The Burglar” was filmed largely on location in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, two places I knew well from babyhood. (I grew up in South Jersey, and we were always in nearby Philly. In the summertime, my family frequently visited pre-casino Atlantic City.) So watching “The Burglar,” I’m seeing landmarks I either recognize cold, or that at least ring a bell.

OK, enough gushing. Let’s get down to synopsizing. Though I’ll tread lightly, spoilers inevitably follow.

The setup

That faux newsreel sets up the story. Its final segment profiles Sister Sara (Phoebe Mackay), a celebrity “spiritualist” — actually, a huckster, we have no trouble recognizing — who lives in a mansion donated to her “cause” by a deceased millionaire. A closeup of a priceless necklace she wears, and a quick description of same, is our clue to its significance in the story about to unfold. (A bonus theme of “The Burglar” is how Sister Sara is as much a thief as the title character.)

When the camera pulls back to the movie-theater audience watching the newsreel, and then to a shot of Duryea in the audience, there is little doubt what’s going on. This guy’s planning to boost that necklace.

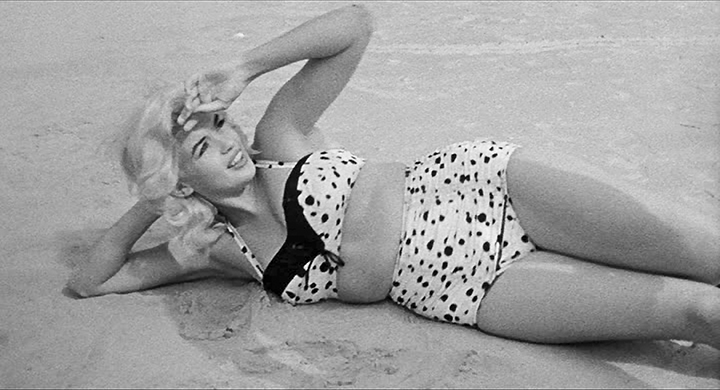

At the door of Sister Sara’s estate, a seemingly demure young woman (Jayne Mansfield) materializes to make a donation of two quarters. When Sister Sara asks if she’s had lunch, the woman looks downward. “You’re having lunch with me — and dinner, too,” Sara says with a smile.

It turns out that the young woman, Gladden, is part of a gang of crooks. She has cased the joint, and presents her findings to her comrades in crime: cool customer Nat (Duryea), skittish Baylock (Peter Capell) and big lug Dohmer (Mickey Shaughnessy). Nat is the brains; Baylock is the jewelry expert; Dohmer is the muscle.

A plan emerges. The heist will hinge on a 15-minute period each evening during which Sister Sara watches her favorite TV program, a newscast delivered by anchor John Facenda (a real-life Philly newsman playing himself).

But on the night, there’s a complication. The men successfully breach the mansion according to plan. But just as Nat starts drilling the wall safe containing the necklace, a pair of beat cops (Stewart Bradley and an unidentified actor) notice the getaway car, which is parked in a suspicious place, and pull up.

Nat wages a top-of-the-head gamble: He interrupts his drilling to bolt out of the mansion and bluff the cops with a story about breaking down and trying to find a mechanic on foot. Nat turns on the charm and keeps his cool while answering the cops’ questions, and they finally drive off. (Digression: “Charming” Nat kinda reminds you of 1940s Duryea.) Nat is left with barely enough time to scurry back into the house and pinch the necklace, mere seconds before John Facenda signs off.

Back at the gang’s seedy headquarters, the men are all suffering the effects of post-traumatic stress. Even Dohmer can barely catch his breath. (This was a close one.) Baylock, squinting through an eyepiece, examines the necklace and determines its worth at $150,000, though a fence will likely only pay $80 grand.

Now comes trouble in paradise. Baylock pushes for a quick sale and a quick cash return. Nat counsels that they wait for “a drop in temperature.” Baylock demands to know why. Nat answers: “The law, Baylock. The local authorities. The blue boys. What do you think they’re doing right now, sleeping?”

(This brings us to the film’s only lapse in judgment. Baylock, who is wanted by the law, gives a wistful speech about his long-held desire to escape to Central America. His rambling speech is accompanied by Latin-style music. The sequence makes you go, “Huh?” Perhaps it is meant to shed some light on Baylock’s motivations? Not necessary. Peter Capell is a very good actor. We know who Baylock is.)

There’s more drama. Sick of Dohmer’s ogling, Gladden says bitterly, “You’re always lookin’ at me!” Arguments ensue, leading to Dohmer grappling with Gladden in a sexually threatening manner before she can break free. This is a toxic situation, a powder keg.

Baylock privately asks Nat why he keeps Gladden around. After all, Baylock has noted, Nat is not romantically interested in her. Nat doesn’t answer Baylock, of course, but a flashback provides viewers with the answer. As a runaway orphan, Nat was taken in by a man named Gerald (Sam Elber), who you might call a kindly burglar. Gerald taught young Nat the tricks of his trade, but still, he was a good “father.” Gladden was Gerald’s daughter, making her Nat’s “sister,” kind of. Nat gave Gerald his solemn word that he would always take care of innocent, vulnerable Gladden.

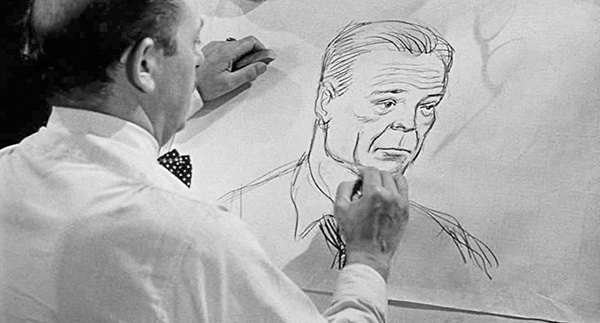

Meanwhile, Philadelphia detectives follow what clues they have. A strong one is the description of Nat provided by those two beat cops who questioned him on the night of the robbery. The pair oversees a police artist’s sketch of the suspect, which turns out to be a very good likeness of Nat.

Another standout in the cast is Martha Vickers as Della, a beautiful stranger who hits on Nat in a bar. Though Nat is wary of Della’s motivations — it seems too good to be true — he yields to her advances. When you’re lonely, you’re lonely.

I’ll reveal no more about the story except to recount a salient line “spoken” by an animatronic figure in a haunted attraction on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. It goes: “We … the dead … welcome you.”

Recognizable locations include Independence Hall, Swann Memorial Fountain, and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia; and Steel Pier, the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Museum, and the Planters Peanuts store on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. They even show the diving horse!

“The Burglar” has my favorite performance by Duryea — it’s made me re-evaluate everything I’ve ever seen him in — as well as my pick for the cinema’s No. 1 noir. It is also Mansfield’s finest acting moment. The actress was so gorgeous, and gorgeously built, that once Hollywood got its claws in her … well, you know what happened. But here, we see a sensitive, thoughtful actress creating a complex character.

P.S.: I once met a cast member of “The Burglar.” Can you guess who? Hint: It wasn’t Jayne Mansfield. Find out who HERE.

P.P.S.: Read my memories of the Planters Peanuts store on the Atlantic City Boardwalk HERE.

More scenes from ‘The Burglar’

‘THE BURGLAR’

Starring Dan Duryea as Nat; Jayne Mansfield as Gladden; Martha Vickers as Della; Peter Capell as Baylock; and Mickey Shaughnessy as Dohmer

Written by David Goodis from his novel

Cinematography by Don Malkames

Art direction by Jim Leonard | Music by Sol Kaplan

Edited by Herta Horn | Produced by Louis W. Kellman

Directed by Paul Wendkos

[Distributed by Columbia Pictures]

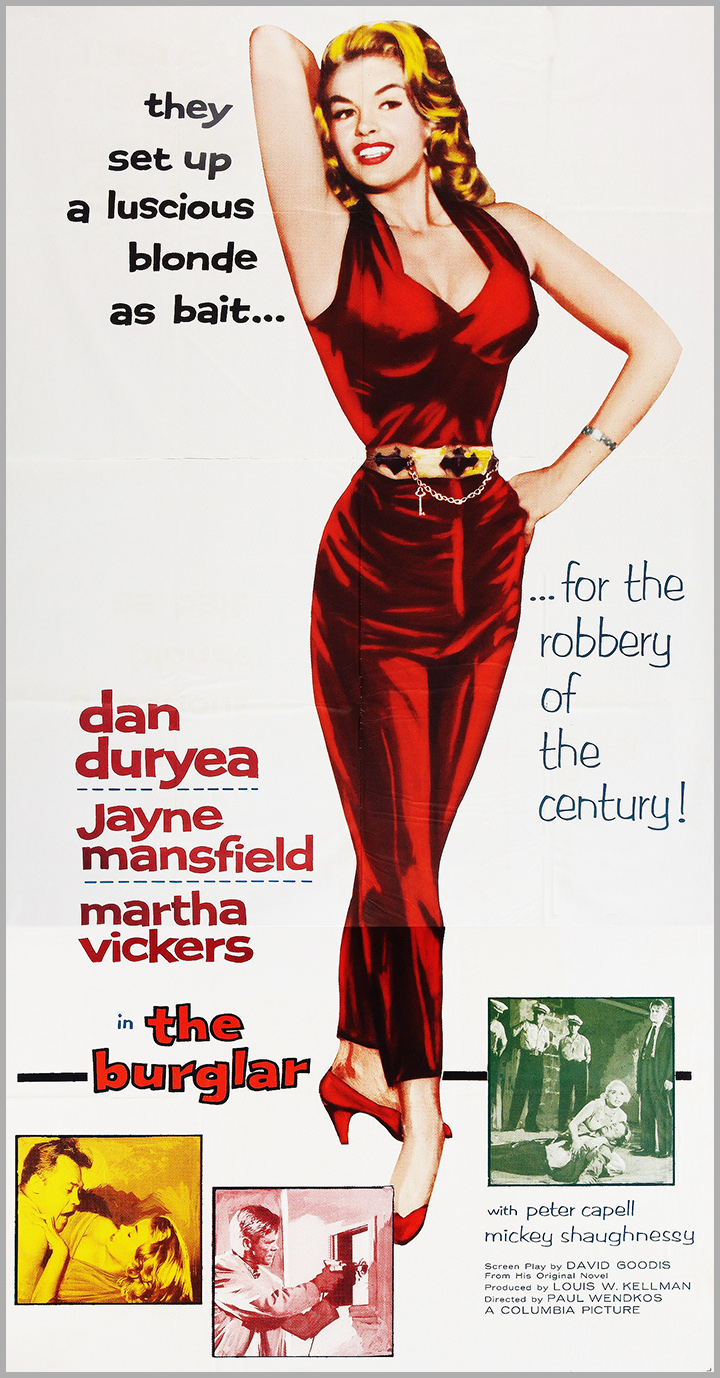

DECEPTIVE ADVERTISING

Dear lord, is this an inappropriate poster. “The Burglar” brought Jayne Mansfield to the attention of Hollywood, but it was released after she became a famous movie star. So obviously, some idiots in marketing figured they’d cash in on Mansfield’s newfound fame. As such, “The Burglar” — a dark, deadly serious, fatalistic noir — was advertised as if it was some kind of sex-kitten comedy. Oh, the humanity!